Theory of Colours (German: Zur Farbenlehre) is a book by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe about the poet’s views on the nature of colours and how these are perceived by humans. It was published in German in 1810 and in English in 1840. The books contains detailed descriptions of phenomena such as coloured shadows, refraction, and chromatic aberration.

The work originated in Goethe’s occupation with painting and mainly exerted an influence on the arts (Philipp Otto Runge, J. M. W. Turner, the Pre-Raphaelites, Wassily Kandinsky). The book is a successor to two short essays entitled “Contributions to Optics”.

Although Goethe’s work was rejected by physicists, a number of philosophers and physicists have concerned themselves with it, including Thomas Johann Seebeck, Arthur Schopenhauer (see: On Vision and Colors), Hermann von Helmholtz, Rudolf Steiner, Ludwig Wittgenstein, Werner Heisenberg, Kurt Gödel, and Mitchell Feigenbaum.

Goethe’s book provides a catalogue of how colour is perceived in a wide variety of circumstances, and considers Isaac Newton’s observations to be special cases. Unlike Newton, Goethe’s concern was not so much with the analytic treatment of colour, as with the qualities of how phenomena are perceived. Philosophers have come to understand the distinction between the optical spectrum, as observed by Newton, and the phenomenon of human colour perception as presented by Goethe—a subject analyzed at length by Wittgenstein in his comments on Goethe’s theory in Remarks on Colour.

Historical background

Goethe’s starting point was the supposed discovery of how Newton erred in the prismatic experiment, and by 1793 Goethe had formulated his arguments against Newton in the essay “Über Newtons Hypothese der diversen Refrangibilität” (“On Newton’s hypothesis of diverse refrangibility”). Yet, by 1794, Goethe had begun to increasingly note the importance of the physiological aspect of colours.

As Goethe notes in the historical section, Louis Bertrand Castel had already published a criticism of Newton’s spectral description of prismatic colour in 1740 in which he observed that the sequence of colours split by a prism depended on the distance from the prism—and that Newton was looking at a special case.

“Whereas Newton observed the colour spectrum cast on a wall at a fixed distance away from the prism, Goethe observed the cast spectrum on a white card which was progressively moved away from the prism… As the card was moved away, the projected image elongated, gradually assuming an elliptical shape, and the coloured images became larger, finally merging at the centre to produce green. Moving the card farther led to the increase in the size of the image, until finally the spectrum described by Newton in the Opticks was produced… The image cast by the refracted beam was not fixed, but rather developed with increasing distance from the prism. Consequently, Goethe saw the particular distance chosen by Newton to prove the second proposition of the Opticks as capriciously imposed.” (Alex Kentsis, Between Light and Eye)

The theory we set up against this begins with colourless light, and avails itself of outward conditions, to produce coloured phenomena; but it concedes worth and dignity to these conditions. It does not arrogate to itself developing colours from the light, but rather seeks to prove by numberless cases that colour is produced by light as well as by what stands against it. — Goethe

In the preface to the Theory of Colours, Goethe explained that he tried to apply the principle of polarity, in the work—a proposition that belonged to his earliest convictions and was constitutive of his entire study of nature.

Goethe’s theory

Goethe’s theory of the constitution of colours of the spectrum has not proved to be an unsatisfactory theory, rather it really isn’t a theory at all. Nothing can be predicted with it. It is, rather a vague schematic outline of the sort we find in James’s psychology. Nor is there any experimentum crucis which could decide for or against the theory.

— Ludwig Wittgenstein, Remarks on Colour, paragraphs 70

It is hard to present Goethe’s “theory”, since he refrains from setting up any actual theory; he says, “its intention is to portray rather than explain” (Scientific Studies). Instead of setting up models and explanations, Goethe collected specimens—he was responsible for the meteorological collections of Jena University. By the time of his death, he had amassed over 17,800 minerals in his personal collection—the largest in all of Europe. He took the same approach to colour—instead of narrowing and isolating things to a single ‘experimentum crucis’ (or critical experiment that would prove or disprove his theory), he sought to gain as much breadth for his understanding as possible by developing a wide-ranging exposition through which is revealed the essential character of colour—without having to resort to explanations and theories about perceived phenomena such as ‘wavelengths’ or ‘particles’.

“The crux of his color theory is its experiential source: rather than impose theoretical statements, Goethe sought to allow light and color to be displayed in an ordered series of experiments that readers could experience for themselves.” (Seamon, 1998). According to Goethe, “Newton’s error.. was trusting math over the sensations of his eye.” (Jonah Lehrer, 2006).

To stay true to the perception without resort to explanation was the essence of Goethe’s method. What he provided was really not so much a theory, as a rational description of colour. For Goethe, “the highest is to understand that all fact is really theory. The blue of the sky reveals to us the basic law of color. Search nothing beyond the phenomena, they themselves are the theory.”

Goethe delivered in full measure what was promised by the title of his excellent work: Data for a Theory of Color. They are important, complete, and significant data, rich material for a future theory of color. He has not, however, undertaken to furnish the theory itself; hence, as he himself remarks and admits on page xxxix of the introduction, he has not furnished us with a real explanation of the essential nature of color, but really postulates it as a phenomenon, and merely tells us how it originates, not what it is. The physiological colors … he represents as a phenomenon, complete and existing by itself, without even attempting to show their relation to the physical colors, his principal theme. … it is really a systematic presentation of facts, but it stops short at this. — Schopenhauer, On Vision and Colors, Introduction

Goethe outlines his method in the essay, The experiment as mediator between subject and object (1772). It underscores his experiential standpoint. “The human being himself, to the extent that he makes sound use of his senses, is the most exact physical apparatus that can exist.” (Goethe, Scientific Studies)

I believe that what Goethe was really seeking was not a physiological but a psychological theory of colours. — Ludwig Wittgenstein, Culture and Value, MS 112 255:26.11.1931

Light and darkness

Unlike his contemporaries, Goethe didn’t see darkness as an absence of light, but rather as polar to and interacting with light; colour resulted from this interaction of light and shadow. For Goethe, light is “the simplest most undivided most homogenous being that we know. Confronting it is the darkness” (Letter to Jacobi).

…they maintained that shade is a part of light. It sounds absurd when I express it; but so it is: for they said that colours, which are shadow and the result of shade, are light itself.

— Johann Eckermann, Conversations of Goethe, entry: January 4, 1824; trans. Wallace Wood

Based on his experiments with turbid media, Goethe characterized colour as arising from the dynamic interplay of darkness and light. Rudolf Steiner, the science editor for the Kurschner edition of Goethe’s works, gave the following analogy:

Modern natural science sees darkness as a complete nothingness. According to this view, the light which streams into a dark space has no resistance from the darkness to overcome. Goethe pictures to himself that light and darkness relate to each other like the north and south pole of a magnet. The darkness can weaken the light in its working power. Conversely, the light can limit the energy of the darkness. In both cases color arises.— Rudolf Steiner, 1897

Experiments with turbid media

Goethe’s studies of colour began with experiments which examined the effects of turbid media, such as air, dust, and moisture on the perception of light and dark. The poet observed that light seen through a turbid medium appears yellow, and darkness seen through an illuminated medium appears blue.

He then proceeds with numerous experiments, systematically observing the effects of rarefied mediums such as dust, air, and moisture on the perception of colour.

Boundary conditions

When looked at through a prism, the colours seen at a light–dark boundary depend upon the orientation of this light–dark boundary.

When viewed through a prism, the orientation of a light–dark boundary with respect to the prism’s axis is significant. With white above a dark boundary, we observe the light extending a blue-violet edge into the dark area; whereas dark above a light boundary results in a red-yellow edge extending into the light area.

Goethe was intrigued by this difference. He felt that this arising of colour at light–dark boundaries was fundamental to the creation of the spectrum (which he considered to be a compound phenomenon).

Varying the experimental conditions by using different shades of grey shows that the intensity of coloured edges increases with boundary contrast.

Light and dark spectra

Light and dark spectra—when coloured edges overlap in a light spectrum, green results; when they overlap in a dark spectrum, magenta results. (Click for animation)

Since the colour phenomenon relies on the adjacency of light and dark, there are two ways to produce a spectrum: with a light beam in a dark room, and with a dark beam (i.e., a shadow) in a light room.

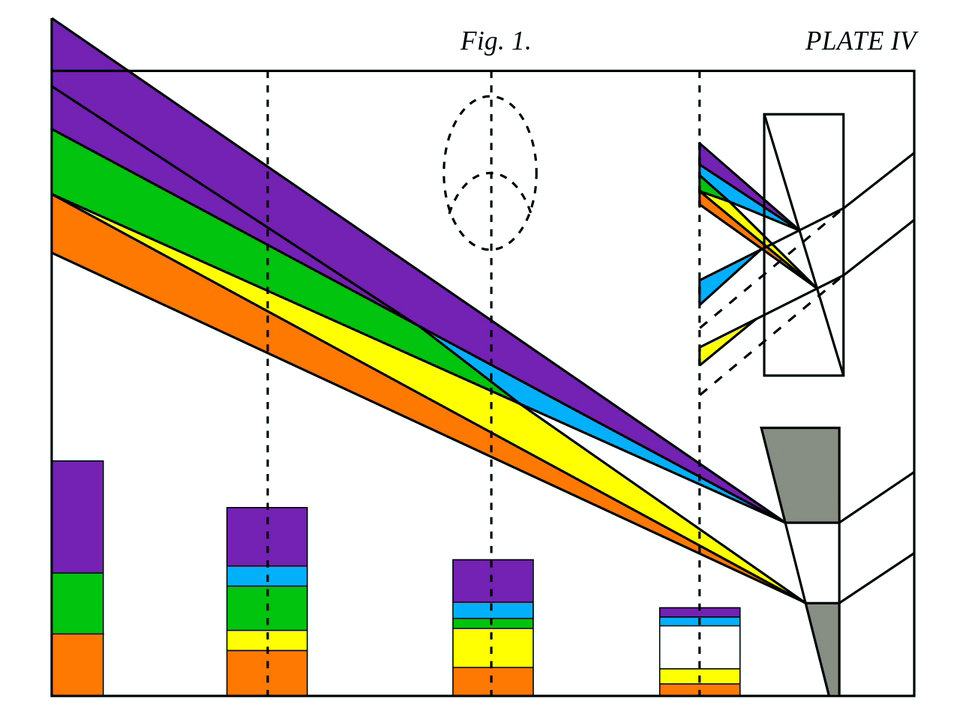

Goethe recorded the sequence of colours projected at various distances from a prism for both cases (see Plate IV, Theory of Colours). In both cases, he found that the yellow and blue edges remain closest to the side which is light, and red and violet edges remain closest to the side which is dark. At a certain distance, these edges overlap—and we obtain Newton’s spectrum. When these edges overlap in a light spectrum, green results; when they overlap in a dark spectrum, magenta results.

With a light spectrum (i.e. a shaft of light in a surrounding darkness), we find yellow-red colours along the top edge, and blue-violet colours along the bottom edge. The spectrum with green in the middle arises only where the blue-violet edges overlap the yellow-red edges. Unfortunately an optical mixture of blue and yellow gives white, not green, and so Goethe’s explanation of Newton’s spectrum fails.

With a dark spectrum (i.e., a shadow surrounded by light), we find violet-blue along the top edge, and red-yellow along the bottom edge—and where these edges overlap, we find (extraspectral) magenta.

Goethe’s colour wheel

When the eye sees a colour it is immediately excited and it is its nature, spontaneously and of necessity, at once to produce another, which with the original colour, comprehends the whole chromatic scale.

— Goethe, Theory of Colours

Goethe anticipated Ewald Hering’s Opponent process theory by proposing a symmetric colour wheel. He writes, “The chromatic circle… arranged in a general way according to the natural order… for the colours diametrically opposed to each other in this diagram are those which reciprocally evoke each other in the eye. Thus, yellow demands violet; orange [demands] blue; purple [demands] green; and vice versa: thus… all intermediate gradations reciprocally evoke each other; the simpler colour demanding the compound, and vice versa ( paragraph #50).

In the same way that light and dark spectra yielded green from the mixture of blue and yellow—Goethe completed his colour wheel by recognising the importance of magenta—”For Newton, only spectral colors could count as fundamental. By contrast, Goethe’s more empirical approach led him to recognize the essential role of magenta in a complete color circle, a role that it still has in all modern color systems.”

Complementary colours and colours psychology

Goethe also included aesthetic qualities in his colour wheel, under the title of “allegorical, symbolic, mystic use of colour” (Allegorischer, symbolischer, mystischer Gebrauch der Farbe), establishing a kind of color psychology. He associated red with the “beautiful”, orange with the “noble”, yellow to the “good”, green to the “useful”, blue to the “common”, and violet to the “unnecessary”. These six qualities were assigned to four categories of human cognition, the rational (Vernunft) to the beautiful and the noble (red and orange), the intellectual (Verstand) to the good and the useful (yellow and green), the sensual (Sinnlichkeit) to the useful and the common (green and blue) and, closing the circle, imagination (Phantasie) to both the unnecessary and the beautiful (purple and red).

Notes on translation

Magenta appeared as a colour term only in the mid-nineteenth century, after Goethe. Hence, references to Goethe’s recognition of magenta are fraught with interpretation. If one observes the colours coming out of a prism—an English person may be more inclined to describe as magenta what in German is called Purpur—so one may not lose the intention of the author.

However, literal translation is more difficult. Goethe’s work uses two composite words for mixed (intermediate) hues along with corresponding usual colour terms such as “orange” and “violet”.

It is not clear how Goethe’s Rot, Purpur (explicitly named as the complementary to green), and Schön (one of the six colour sectors) are related between themselves and to the red tip of the visible spectrum. The text about interference from the “physical” chapter does not consider Rot and Purpur synonymous. Also, Purpur is certainly distinct from Blaurot, because Purpur is named as a colour which lies somewhere between Blaurot and Gelbrot (, paragraph 476), although possibly not adjacent to the latter. This article uses the English translations from the above table.

Newton and Goethe

“The essential difference between Goethe’s theory of colour and the theory which has prevailed in science (despite all modifications) since Newton’s day, lies in this: While the theory of Newton and his successors was based on excluding the colour-seeing faculty of the eye, Goethe founded his theory on the eye’s experience of colour.”

“The renouncing of life and immediacy, which was the premise for the progress of natural science since Newton, formed the real basis for the bitter struggle which Goethe waged against the physical optics of Newton. It would be superficial to dismiss this struggle as unimportant: there is much significance in one of the most outstanding men directing all his efforts to fighting against the development of Newtonian optics.” (Werner Heisenberg, during a speech celebrating Goethe’s birthday)

Due to their different approaches to a common subject, many misunderstandings have arisen between Newton’s mathematical understanding of optics, and Goethe’s experiential approach.

Because Newton understands white light to be composed of individual colours, and Goethe sees colour arising from the interaction of light and dark, they come to different conclusions on the question: is the optical spectrum a primary or a compound phenomenon?

For Newton, the prism is immaterial to the existence of colour, as all the colours already exist in white light, and the prism merely fans them out according to their refrangibility. Goethe sought to show that, as a turbid medium, the prism was an integral factor in the arising of colour.

Whereas Newton narrowed the beam of light in order to isolate the phenomenon, Goethe observed that with a wider aperture, there was no spectrum. He saw only reddish-yellow edges and blue-cyan edges with white between them, and the spectrum arose only where these edges came close enough to overlap. For him, the spectrum could be explained by the simpler phenomena of colour arising from the interaction of light and dark edges.

Newton explains the appearance of white with colored edges by saying that due to the differing overall amount of refraction, the rays mix together to create a full white towards the centre, whereas the edges do not benefit from this full mixture and appear with greater red or blue components. For Newton’s account of his experiments, see his Opticks (1704).

Goethe’s reification of darkness is rejected by modern physics. Both Newton and Huygens defined darkness as an absence of light. Young and Fresnel combined Newton’s particle theory with Huygen’s wave theory to show that colour is the visible manifestation of light’s wavelength. Physicists today attribute both a corpuscular and undulatory character to light—comprising the wave–particle duality.

History and influence

The first edition of the Farbenlehre was printed at the Cotta’schen Verlagsbuchhandlung on May 16, 1810, with 250 copies on grey paper and 500 copies on white paper. It contained three sections: i) a didactic section in which Goethe presents his own observations, ii) a polemic section in which he makes his case against Newton, and iii) a historical section.

From its publication, the book was controversial for its stance against Newton. So much so, that when Charles Eastlake translated the text into English in 1840, he omitted the content of Goethe’s polemic against Newton.

Significantly (and regrettably), only the ‘Didactic’ colour observations appear in Eastlake’s translation. In his preface, Eastlake explains that he deleted the historical and entoptic parts of the book because they ‘lacked scientific interest’, and censored Goethe’s polemic because the ‘violence of his objections’ against Newton would prevent readers from fairly judging Goethe’s color observations. — Bruce MacEvoy, Handprint.com, 2008

Influence on the arts

Goethe was initially induced to occupy himself with the study of colour by the questions of hue in painting. “During his first journey to Italy (1786–88), he noticed that artists were able to enunciate rules for virtually all the elements of painting and drawing except color and coloring. In the years 1786–88, Goethe began investigating whether one could ascertain rules to govern the artistic use of color.”

This aim came to some fulfillment when several pictorial artists, above all Philipp Otto Runge, took an interest in his colour studies. After being translated into English by Charles Eastlake in 1840, the theory became widely adopted by the art world—especially among the Pre-Raphaelites. J. M. W. Turner studied it comprehensively and referenced it in the titles of several paintings. Wassily Kandinsky considered it “one of the most important works.”

Influence on Latin American flags

Flag of Colombia

During a party in Weimar in the winter of 1785, Goethe had a late-night conversation with the South American revolutionary Francisco de Miranda. In a letter written to Count Semyon Romanovich Vorontsov (1792), Miranda recounted how Goethe, fascinated with his exploits throughout the Americas and Europe, told him, “Your destiny is to create in your land a place where primary colours are not distorted.” He proceeded to clarify what he meant:

“ First he explained to me the way the iris transforms the light into the three primary colours… then he said, “Why yellow is the most warm, noble and closest to the bright light; why Blue is that mix of excitement and serenity, so far that it evokes the shadows; and why Red is the exaltation of Yellow and Blue, the synthesis, the vanishing of the bright light into the shadows”. ”

Influence on philosophers

In the nineteenth century Goethe’s Theory was taken up by Schopenhauer in On Vision and Colors, who developed it into a kind of arithmetical physiology of the action of the retina, much in keeping with his own representative realism.

In the twentieth century the theory was transmitted to philosophy via Wittgenstein, who devoted a series of remarks to the subject at the end of his life. These remarks are collected as Remarks on Colour, (Wittgenstein, 1977).

Someone who agrees with Goethe finds that Goethe correctly recognized the nature of colour. And here ‘nature’ does not mean a sum of experiences with respect to colours, but it is to be found in the concept of colour.— Aphorism 125, Ludwig Wittgenstein, Remarks on Color, 1992

Wittgenstein was interested in the fact that some propositions about colour are apparently neither empirical nor exactly a priori, but something in between: phenomenology, according to Goethe. However, Wittgenstein took the line that ‘There is no such thing as phenomenology, though there are phenomenological problems.’ He was content to regard Goethe’s observations as a kind of logic or geometry. Wittgenstein took his examples from the Runge letter included in the “Farbenlehre”, e.g. “White is the lightest colour”, “There cannot be a transparent white”, “There cannot be a reddish green”, and so on. The logical status of these propositions in Wittgenstein’s investigation, including their relation to physics, has been discussed in Jonathan Westphal’s Colour: a Philosophical Introduction (Westphal, 1991).

Source From Wikipedia