Eye color is a polygenic phenotypic character determined by two distinct factors: the pigmentation of the eye’s iris and the frequency-dependence of the scattering of light by the turbid medium in the stroma of the iris.

In humans, the pigmentation of the iris varies from light brown to black, depending on the concentration of melanin in the iris pigment epithelium (located on the back of the iris), the melanin content within the iris stroma (located at the front of the iris), and the cellular density of the stroma. The appearance of blue and green, as well as hazel eyes, results from the Tyndall scattering of light in the stroma, a phenomenon similar to that which accounts for the blueness of the sky called Rayleigh scattering. Neither blue nor green pigments are ever present in the human iris or ocular fluid. Eye color is thus an instance of structural color and varies depending on the lighting conditions, especially for lighter-colored eyes.

The brightly colored eyes of many bird species result from the presence of other pigments, such as pteridines, purines, and carotenoids. Humans and other animals have many phenotypic variations in eye color. The genetics of eye color are complicated, and color is determined by multiple genes. So far, as many as 15 genes have been associated with eye color inheritance. Some of the eye-color genes include OCA2 and HERC2. The earlier belief that blue eye color is a simple recessive trait has been shown to be incorrect. The genetics of eye color are so complex that almost any parent-child combination of eye colors can occur. However, OCA2 gene polymorphism, close to proximal 5′ regulatory region, explains most human eye-color variation.

Genetic determination

Eye color is an inherited trait influenced by more than one gene. These genes are sought using associations to small changes in the genes themselves and in neighboring genes. These changes are known as single-nucleotide polymorphisms or SNPs. The actual number of genes that contribute to eye color is currently unknown, but there are a few likely candidates. A study in Rotterdam (2009) found that it was possible to predict eye color with more than 90% accuracy for brown and blue using just six SNPs. There is evidence that as many as 16 different genes could be responsible for eye color in humans; however, the main two genes associated with eye color variation are OCA2 and HERC2, and both are localized in Chromosome 15.

The gene OCA2 (OMIM: 203200), when in a variant form, causes the pink eye color and hypopigmentation common in human albinism. (The name of the gene is derived from the disorder it causes, oculocutaneous albinism type II.) Different SNPs within OCA2 are strongly associated with blue and green eyes as well as variations in freckling, mole counts, hair and skin tone. The polymorphisms may be in an OCA2 regulatory sequence, where they may influence the expression of the gene product, which in turn affects pigmentation. A specific mutation within the HERC2 gene, a gene that regulates OCA2 expression, is partly responsible for blue eyes. Other genes implicated in eye color variation are SLC24A4 and TYR.

Gene name Effect on eye color

OCA2 Associated with melanin producing cells. Central importance to eye color.

HERC2 Affects function of OCA2, with a specific mutation strongly linked to blue eyes.

SLC24A4 Associated with differences between blue and green eyes.

TYR Associated with differences between blue and green eyes.

Blue eyes with a brown spot, green eyes, and gray eyes are caused by an entirely different part of the genome.

Ancient DNA and eye color in Europe

People of European descent show the greatest variety in eye color of any population worldwide. Recent advances in ancient DNA technology have revealed some of the history of eye color in Europe. All European Mesolithic hunter-gatherer remains so far investigated have shown genetic markers for light-colored eyes, in the case of western and central European hunter-gatherers combined with dark skin color. The later additions to the European gene pool, the Early Neolithic farmers from Anatolia and the Yamnaya Copper Age/Bronze Age pastoralists (possibly the Proto-Indo-European population) from the area north of the Black Sea appear to have had much higher incidences of dark eye color alleles, and alleles giving rise to lighter skin, than the original European population.

Classification of color

Iris color can provide a large amount of information about a person, and a classification of colors may be useful in documenting pathological changes or determining how a person may respond to ocular pharmaceuticals. Classification systems have ranged from a basic light or dark description to detailed gradings employing photographic standards for comparison. Others have attempted to set objective standards of color comparison.

Eye colors range from the darkest shades of brown to the lightest tints of blue. To meet the need for standardized classification, at once simple yet detailed enough for research purposes, Seddon et al. developed a graded system based on the predominant iris color and the amount of brown or yellow pigment present. There are three pigment colors that determine, depending on their proportion, the outward appearance of the iris, along with structural color. Green irises, for example, have blue and some yellow. Brown irises contain mostly brown. Some eyes have a dark ring around the iris, called a limbal ring.

Eye color in non-human animals is regulated differently. For example, instead of blue as in humans, autosomal recessive eye color in the skink species Corucia zebrata is black, and the autosomal dominant color is yellow-green.

As the perception of color depends on viewing conditions (e.g., the amount and kind of illumination, as well as the hue of the surrounding environment), so does the perception of eye color.

Changes in eye color

Most new-born babies who have European ancestry have light-colored eyes. As the child develops, melanocytes (cells found within the iris of human eyes, as well as skin and hair follicles) slowly begin to produce melanin. Because melanocyte cells continually produce pigment, in theory eye color can be changed. Adult eye color is usually established between 3 and 6 months of age, though this can be later. Observing the iris of an infant from the side using only transmitted light with no reflection from the back of the iris, it is possible to detect the presence or absence of low levels of melanin. An iris that appears blue under this method of observation is more likely to remain blue as the infant ages. An iris that appears golden contains some melanin even at this early age and is likely to turn from blue to green or brown as the infant ages.

Changes (lightening or darkening) of eye colors during early childhood, puberty, pregnancy, and sometimes after serious trauma (like heterochromia) do represent cause for a plausible argument stating that some eyes can or do change, based on chemical reactions and hormonal changes within the body.

Studies on Caucasian twins, both fraternal and identical, have shown that eye color over time can be subject to change, and major demelanization of the iris may also be genetically determined. Most eye-color changes have been observed or reported in the Caucasian population with hazel and amber eyes.

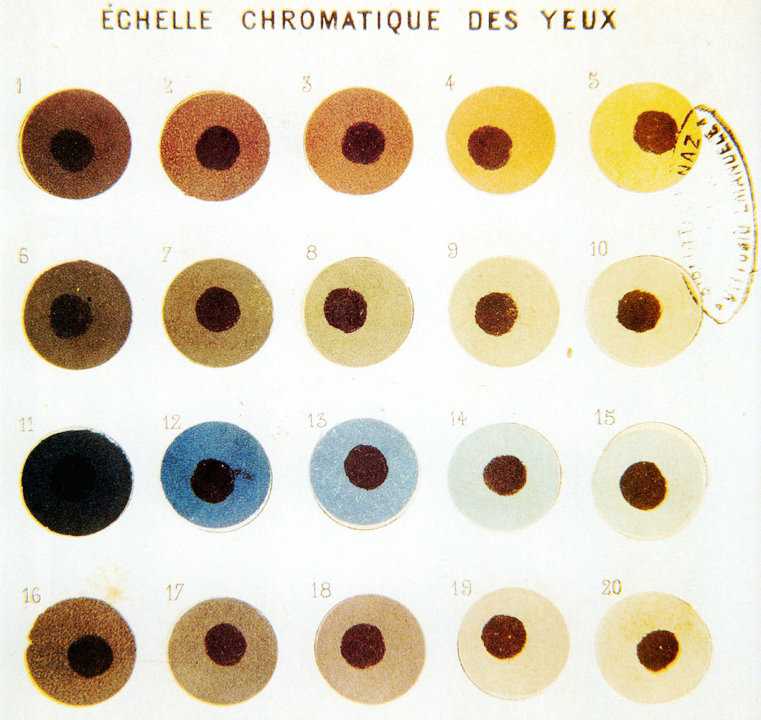

Eye color chart (Martin scale)

Carleton Coon created a chart by the original Martin scale. The numbering is reversed on the scale below in the (later) Martin–Schultz scale, which is (still) used in physical anthropology.

Light and light-mixed eyes (16–12 in Martin scale)

Pure light (16–15 in Martin scale)

16: pure light blue

15: gray

Light-mixed (14–12 in Martin scale)

14: Very light-mixed (blue with gray or green or green with gray)

13-12: Light-mixed (light or very light-mixed with small admixture of brown)

Mixed eyes (11–7 in Martin scale) Mixture of light eyes (blue, gray or green) with brown when light and brown appearance is at the same level.

Dark and dark-mixed eyes (6–1 in Martin scale)

Dark-mixed: 6–5 in Martin scale. Brown with small admixture of light

Dark: 4–1 in Martin scale. Brown (light brown and dark brown) and very dark brown (almost black)

Amber

Amber eyes are of a solid color and have a strong yellowish/golden and russet/coppery tint. This may be due to the deposition of the yellow pigment called lipochrome in the iris (which is also found in green eyes). Amber eyes should not be confused with hazel eyes; although hazel eyes may contain specks of amber or gold, they usually tend to comprise many other colors, including green, brown and orange. Also, hazel eyes may appear to shift in color and consist of flecks and ripples, while amber eyes are of a solid gold hue. Even though amber is considered to be like gold, some people have russet or copper colored amber eyes that many people mistake for hazel, though hazel tends to be duller and contains green with red/gold flecks, as mentioned above. Amber eyes may also contain amounts of very light gold-ish gray.

The eyes of some pigeons contain yellow fluorescing pigments known as pteridines. The bright yellow eyes of the great horned owl are thought to be due to the presence of the pteridine pigment xanthopterin within certain chromatophores (called xanthophores) located in the iris stroma. In humans, yellowish specks or patches are thought to be due to the pigment lipofuscin, also known as lipochrome. Many animals such as canines, domestic cats, owls, eagles, pigeons and fish have amber eyes as a common color, whereas in humans this color occurs less frequently.

Blue

There is no blue pigmentation either in the iris or in the ocular fluid. Dissection reveals that the iris pigment epithelium is brownish black due to the presence of melanin. Unlike brown eyes, blue eyes have low concentrations of melanin in the stroma of the iris, which lies in front of the dark epithelium. Longer wavelengths of light tend to be absorbed by the dark underlying epithelium, while shorter wavelengths are reflected and undergo Rayleigh scattering in the turbid medium of the stroma. This is the same frequency-dependence of scattering that accounts for the blue appearance of the sky.:9 The result is a “Tyndall blue” structural color that varies with external lighting conditions.

In humans, the inheritance pattern followed by blue eyes is considered similar to that of a recessive trait (in general, eye color inheritance is considered a polygenic trait, meaning that it is controlled by the interactions of several genes, not just one). In 2008, new research tracked down a single genetic mutation that leads to blue eyes. “Originally, we all had brown eyes,” said Eiberg. Eiberg and colleagues suggested in a study published in Human Genetics that a mutation in the 86th intron of the HERC2 gene, which is hypothesized to interact with the OCA2 gene promoter, reduced expression of OCA2 with subsequent reduction in melanin production. The authors suggest that the mutation may have arisen in the northwestern part of the Black Sea region, but add that it is “difficult to calculate the age of the mutation.”

Blue eyes are common in northern and eastern Europe, particularly around the Baltic Sea. Blue eyes are also found in southern Europe, Central Asia, South Asia, North Africa and West Asia. In West Asia, a proportion of Israelis are of Ashkenazi origin, among whom the trait is relatively elevated (a study taken in 1911 found that 53.7% of Ukrainian Jews had blue eyes).

The same DNA sequence in the region of the OCA2 gene among blue-eyed people suggests they may have a single common ancestor.

DNA studies on ancient human remains confirm that light skin, hair and eyes were present at least tens of thousands of years ago on Neanderthals, who lived in Eurasia for 500,000 years. As of 2016, the earliest light-pigmented and blue-eyed remains of Homo Sapiens were found in 7,700 years old Mesolithic hunter-gatherers from Motala, Sweden.

A 2002 study found that the prevalence of blue eye color among the white population in the United States to be 33.8% for those born from 1936 through 1951 compared with 57.4 percent for those born from 1899 through 1905. As of 2006, one out of every six people, or 16.6% of the total population, and 22.3% of whites, has blue eyes. Blue eyes are continuing to become less common among American children.

Blue eyes are rare in mammals; one example is the recently discovered marsupial, the blue-eyed spotted cuscus (Spilocuscus wilsoni). The trait is hitherto known only from a single primate other than humans – Sclater’s lemur (Eulemur flavifrons) of Madagascar. While some cats and dogs have blue eyes, this is usually due to another mutation that is associated with deafness. But in cats alone, there are four identified gene mutations that produce blue eyes, some of which are associated with congenital neurological disorders. The mutation found in the Siamese cats is associated with strabismus (crossed eyes). The mutation found in blue-eyed solid white cats (where the coat color is caused by the gene for “epistatic white”) is linked with deafness. However, there are phenotypically identical, but genotypically different, blue-eyed white cats (where the coat color is caused by the gene for white spotting) where the coat color is not strongly associated with deafness. In the blue-eyed Ojos Azules breed, there may be other neurological defects. Blue-eyed non-white cats of unknown genotype also occur at random in the cat population.

Brown

In humans, brown eyes result from a relatively high concentration of melanin in the stroma of the iris, which causes light of both shorter and longer wavelengths to be absorbed.

Dark brown eyes are dominant in humans and in many parts of the world, it is nearly the only iris color present. Dark pigment of brown eyes is common in Europe, South Europe, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Central Asia, South Asia, West Asia, Oceania, Africa, Americas, etc. as well as parts of Eastern Europe and Southern Europe. The majority of people in the world overall have brown eyes to dark brown eyes.

Light or medium-pigmented brown eyes can also be commonly found in South Europe, among the Americas, and parts of Central Asia (Middle East and South Asia).

Gray

Like blue eyes, gray eyes have a dark epithelium at the back of the iris and a relatively clear stroma at the front. One possible explanation for the difference in the appearance of gray and blue eyes is that gray eyes have larger deposits of collagen in the stroma, so that the light that is reflected from the epithelium undergoes Mie scattering (which is not strongly frequency-dependent) rather than Rayleigh scattering (in which shorter wavelengths of light are scattered more). This would be analogous to the change in the color of the sky, from the blue given by the Rayleigh scattering of sunlight by small gas molecules when the sky is clear, to the gray caused by Mie scattering of large water droplets when the sky is cloudy. Alternatively, it has been suggested that gray and blue eyes might differ in the concentration of melanin at the front of the stroma.

Gray eyes are most common in Northern and Eastern Europe. Gray eyes can also be found among the Algerian Shawia people of the Aurès Mountains in Northwest Africa, in the Middle East, Central Asia, and South Asia. Under magnification, gray eyes exhibit small amounts of yellow and brown color in the iris.

Green

As with blue eyes, the color of green eyes does not result simply from the pigmentation of the iris. The green color is caused by the combination of: 1) an amber or light brown pigmentation in the stroma of the iris (which has a low or moderate concentration of melanin) with: 2) a blue shade created by the Rayleigh scattering of reflected light. Green eyes contain the yellowish pigment lipochrome.

Green eyes probably result from the interaction of multiple variants within the OCA2 and other genes. They were present in south Siberia during the Bronze Age.

They are most common in Northern, Western and Central Europe. In Ireland and Scotland 14% of people have brown eyes and 86% have either blue or green eyes, In Iceland, 89% of women and 87% of men have either blue or green eye color. A study of Icelandic and Dutch adults found green eyes to be much more prevalent in women than in men. Among European Americans, green eyes are most common among those of recent Celtic and Germanic ancestry, about 16%. 37.2% of Italians from Verona and 56% of Slovenes have blue/green eyes.

Green eyes are common in Tabby cats as well as the Chinchilla Longhair and its shorthaired equivalents are notable for their black-rimmed sea-green eyes.

Hazel

Hazel eyes are due to a combination of Rayleigh scattering and a moderate amount of melanin in the iris’ anterior border layer. Hazel eyes often appear to shift in color from a brown to a green. Although hazel mostly consists of brown and green, the dominant color in the eye can either be brown/gold or green. This is how many people mistake hazel eyes to be amber and vice versa. This can sometimes produce a multicolored iris, i.e., an eye that is light brown/amber near the pupil and charcoal or dark green on the outer part of the iris (or vice versa) when observed in sunlight.

Definitions of the eye color hazel vary: it is sometimes considered to be synonymous with light brown or gold, as in the color of a hazelnut shell.

Hazel eyes occur throughout Caucasoid populations, in particular in regions where blue, green and brown eyed peoples are intermixed.

Red and violet

“Red” albino eyes

The eyes of people with severe forms of albinism may appear red under certain lighting conditions owing to the extremely low quantities of melanin, allowing the blood vessels to show through. In addition, flash photography can sometimes cause a “red-eye effect”, in which the very bright light from a flash reflects off the retina, which is abundantly vascular, causing the pupil to appear red in the photograph. Although the deep blue eyes of some people such as Elizabeth Taylor can appear violet at certain times, “true” violet-colored eyes occur only due to albinism.

Medical implications

Those with lighter iris color have been found to have a higher prevalence of age-related macular degeneration (ARMD) than those with darker iris color; lighter eye color is also associated with an increased risk of ARMD progression. A gray iris may indicate the presence of a uveitis, and an increased risk of uveal melanoma has been found in those with blue, green or gray eyes. However, a study in 2000 suggests that people with dark brown eyes are at increased risk of developing cataracts and therefore should protect their eyes from direct exposure to sunlight.

Wilson’s disease

Wilson’s disease involves a mutation of the gene coding for the enzyme ATPase7B, which prevents copper within the liver from entering the Golgi apparatus in cells. Instead, the copper accumulates in the liver and in other tissues, including the iris of the eye. This results in the formation of Kayser–Fleischer rings, which are dark rings that encircle the periphery of the iris.

Coloration of the sclera

Eye color outside of the iris may also be symptomatic of disease. Yellowing of the sclera (the “whites of the eyes”) is associated with jaundice, and may be symptomatic of liver diseases such as cirrhosis or hepatitis. A blue coloration of the sclera may also be symptomatic of disease. In general, any sudden changes in the color of the sclera should be addressed by a medical professional.

rings that encircle the periphery of the iris.

Coloration of the sclera

Eye color outside of the iris may also be symptomatic of disease. Yellowing of the sclera (the “whites of the eyes”) is associated with jaundice, and may be symptomatic of liver diseases such as cirrhosis or hepatitis. A blue coloration of the sclera may also be symptomatic of disease. In general, any sudden changes in the color of the sclera should be addressed by a medical professional.

Anomalous conditions

Aniridia

Aniridia is a congenital condition characterized by an extremely underdeveloped iris, which appears absent on superficial examination.

Ocular albinism and eye color

Normally, there is a thick layer of melanin on the back of the iris. Even people with the lightest blue eyes, with no melanin on the front of the iris at all, have dark brown coloration on the back of it, to prevent light from scattering around inside the eye. In those with milder forms of albinism, the color of the iris is typically blue but can vary from blue to brown. In severe forms of albinism, there is no pigment on the back of the iris, and light from inside the eye can pass through the iris to the front. In these cases, the only color seen is the red from the hemoglobin of the blood in the capillaries of the iris. Such albinos have pink eyes, as do albino rabbits, mice, or any other animal with a total lack of melanin. Transillumination defects can almost always be observed during an eye examination due to lack of iridial pigmentation. The ocular albino also lacks normal amounts of melanin in the retina as well, which allows more light than normal to reflect off the retina and out of the eye. Because of this, the pupillary reflex is much more pronounced in albino individuals, and this can emphasize the red eye effect in photographs.

Heterochromia

Heterochromia (heterochromia iridum or heterochromia iridis) is an eye condition in which one iris is a different color from the other (complete heterochromia), or where a part of one iris is a different color from the remainder (partial heterochromia or sectoral heterochromia). It is a result of the relative excess or lack of pigment within an iris or part of an iris, which may be inherited or acquired by disease or injury. This uncommon condition usually results due to uneven melanin content. A number of causes are responsible, including genetic, such as chimerism, Horner’s syndrome and Waardenburg syndrome.

A chimera can have two different colored eyes just like any two siblings can—because each cell has different eye color genes. A mosaic can have two different colored eyes if the DNA difference happens to be in an eye-color gene.

There are many other possible reasons for having two different-colored eyes. For example, the film actor Lee Van Cleef was born with one blue eye and one green eye, a trait that reportedly was common in his family, suggesting that it was a genetic trait. This anomaly, which film producers thought would be disturbing to film audiences, was “corrected” by having Van Cleef wear brown contact lenses. David Bowie, on the other hand, had the appearance of different eye colors due to an injury that caused one pupil to be permanently dilated.

Another hypothesis about heterochromia is that it can result from a viral infection in utero affecting the development of one eye, possibly through some sort of genetic mutation. Occasionally, heterochromia can be a sign of a serious medical condition.

A common cause in females with heterochromia is X-inactivation, which can result in a number of heterochromatic traits, such as calico cats. Trauma and certain medications, such as some prostaglandin analogues, can also cause increased pigmentation in one eye. On occasion, a difference in eye color is caused by blood staining the iris after injury.

Source From Wikipedia