Color blindness, also known as color vision deficiency, is the decreased ability to see color or differences in color. Color blindness can make some educational activities difficult. Buying fruit, picking clothing, and reading traffic lights can be more challenging, for example. Problems, however, are generally minor and most people adapt. People with total color blindness, however, may also have decreased visual acuity and be uncomfortable in bright environments.

The most common cause of color blindness is an inherited fault in the development of one or more of the three sets of color sensing cones in the eye. Males are more likely to be color blind than females, as the genes responsible for the most common forms of color blindness are on the X chromosome. As females have two X chromosomes, a defect in one is typically compensated for by the other, while males only have one X chromosome. Color blindness can also result from physical or chemical damage to the eye, optic nerve, or parts of the brain. Diagnosis is typically with the Ishihara color test; however a number of other testing methods also exist.

There is no cure for color blindness. Diagnosis may allow a person’s teacher to change their method of teaching to accommodate the decreased ability to recognize colors. Special lenses may help people with red–green color blindness when under bright conditions. There are also mobile apps that can help people identify colors.

Red–green color blindness is the most common form, followed by blue–yellow color blindness and total color blindness. Red–green color blindness affects up to 8% of males and 0.5% of females of Northern European descent. The ability to see color also decreases in old age. Being color blind may make people ineligible for certain jobs in certain countries. This may include pilot, train driver, and armed forces. The effect of color blindness on artistic ability, however, is controversial. The ability to draw appears to be unchanged and a number of famous artists are believed to have been color blind.

Signs and symptoms

In almost all cases, color blind people retain blue–yellow discrimination, and most color-blind individuals are anomalous trichromats rather than complete dichromats. In practice, this means that they often retain a limited discrimination along the red–green axis of color space, although their ability to separate colors in this dimension is reduced. Color blindness very rarely refers to complete monochromatism.

Dichromats often confuse red and green items. For example, they may find it difficult to distinguish a Braeburn apple from a Granny Smith or red from green of traffic lights without other clues—for example, shape or position. Dichromats tend to learn to use texture and shape clues and so may be able to penetrate camouflage that has been designed to deceive individuals with normal color vision.

Colors of traffic lights are confusing to some dichromats as there is insufficient apparent difference between the red/amber traffic lights and sodium street lamps; also, the green can be confused with a grubby white lamp. This is a risk on high-speed undulating roads where angular cues cannot be used. British Rail color lamp signals use more easily identifiable colors: The red is blood red, the amber is yellow and the green is a bluish color. Most British road traffic lights are mounted vertically on a black rectangle with a white border (forming a “sighting board”) and so dichromats can more easily look for the position of the light within the rectangle—top, middle or bottom. In the eastern provinces of Canada horizontally mounted traffic lights are generally differentiated by shape to facilitate identification for those with color blindness. In the United States, this is not done by shape but by position, as the red light is always on the left if the light is horizontal, or on top if the light is vertical. However, a lone flashing light (e.g. red for stop, yellow for caution) is still problematic.

Causes

Color vision deficiencies can be classified as acquired or inherited.

Acquired: Diseases, drugs (e.g., Plaquenil), and chemicals may cause color blindness.

Inherited: There are three types of inherited or congenital color vision deficiencies: monochromacy, dichromacy, and anomalous trichromacy.

Monochromacy, also known as “total color blindness”, is the lack of ability to distinguish colors (and thus the person views everything as if it were on a black and white television); caused by cone defect or absence. Monochromacy occurs when two or all three of the cone pigments are missing and color and lightness vision is reduced to one dimension.

Rod monochromacy (achromatopsia) is an exceedingly rare, nonprogressive inability to distinguish any colors as a result of absent or nonfunctioning retinal cones. It is associated with light sensitivity (photophobia), involuntary eye oscillations (nystagmus), and poor vision.

Cone monochromacy is a rare total color blindness that is accompanied by relatively normal vision, electroretinogram, and electrooculogram. Cone monochromacy can also be a result of having more than one type of dichromatic color blindness. People who have, for instance, both protanopia and tritanopia are considered to have cone monochromacy. Since cone monochromacy is the lack of/damage of more than one cone in retinal environment, having two types of dichromacy would be an equivalent.

Dichromacy is a moderately severe color vision defect in which one of the three basic color mechanisms is absent or not functioning. It is hereditary and, in the case of protanopia or deuteranopia, sex-linked, affecting predominantly males. Dichromacy occurs when one of the cone pigments is missing and color is reduced to two dimensions. Dichromacy conditions are labeled based on whether the “first” (Greek: prot-, referring to the red photoreceptors), “second” (deuter-, the green), or “third” (trit-, the blue) photoreceptors are affected.

Protanopia is a severe type of color vision deficiency caused by the complete absence of red retinal photoreceptors. Protans have difficulties distinguishing between blue and green colors and also between red and green colors. It is a form of dichromatism in which the subject can only perceive light wavelengths from 400 to 650 nm, instead of the usual 700 nm. Pure reds cannot be seen, instead appearing black; purple colors cannot be distinguished from blues; more orange-tinted reds may appear as very dim yellows, and all orange–yellow–green shades of too long a wavelength to stimulate the blue receptors appear as a similar yellow hue. It is hereditary, sex-linked, and present in 1% of males.

Deuteranopia is a type of color vision deficiency where the green photoreceptors are absent. It affects hue discrimination in the same way as protanopia, but without the dimming effect. Like protanopia, it is hereditary, sex-linked, and found in about 1% of the male population.

Tritanopia is a very rare color vision disturbance in which there are only two cone pigments present and a total absence of blue retinal receptors. Blues appear greenish, yellows and oranges appear pinkish, and purple colors appear deep red. It is related to chromosome 7. Unlike protanopia and deuteranopia, tritanopia and tritanomaly are not sex-linked traits and can be acquired rather than inherited and can be reversed in some cases.

Anomalous trichromacy is a common type of inherited color vision deficiency, occurring when one of the three cone pigments is altered in its spectral sensitivity.

Protanomaly is a mild color vision defect in which an altered spectral sensitivity of red retinal receptors (closer to green receptor response) results in poor red–green hue discrimination. It is hereditary, sex-linked, and present in 1% of males. The difference with protanopia is that in this case the L-cone is present but malfunctioning, whereas in the earlier the L-cone is completely missing.

Deuteranomaly, caused by a similar shift in the green retinal receptors, is by far the most common type of color vision deficiency, mildly affecting red–green hue discrimination in 5% of European males. It is hereditary and sex-linked. The difference with deuteranopia is that in this case the green sensitive cones are not missing but malfunctioning.

Tritanomaly is a rare, hereditary color vision deficiency affecting blue–green and yellow–red/pink hue discrimination. It is related to chromosome “7”. The difference is that the S-cone is malfunctioning but not missing.

Genetics

Color blindness is typically inherited. It is most commonly inherited from mutations on the X chromosome but the mapping of the human genome has shown there are many causative mutations—mutations capable of causing color blindness originate from at least 19 different chromosomes and 56 different genes (as shown online at the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM)). Two of the most common inherited forms of color blindness are protanomaly (and, more rarely, protanopia – the two together often known as “protans”) and deuteranomaly (or, more rarely, deuteranopia – the two together often referred to as “deutans”). Both “protans” and “deutans” (of which the deutans are by far the most common) are known as “red–green color-blind” which is present in about 8 percent of human males and 0.6 percent of females of Northern European ancestry.

Some of the inherited diseases known to cause color blindness are:

cone dystrophy

cone-rod dystrophy

achromatopsia (a.k.a. rod monochromatism, stationary cone dystrophy or cone dysfunction syndrome)

blue cone monochromatism (a.k.a. blue cone monochromacy or X-linked achromatopsia)

Leber’s congenital amaurosis

retinitis pigmentosa (initially affects rods but can later progress to cones and therefore color blindness).

Inherited color blindness can be congenital (from birth), or it can commence in childhood or adulthood. Depending on the mutation, it can be stationary, that is, remain the same throughout a person’s lifetime, or progressive. As progressive phenotypes involve deterioration of the retina and other parts of the eye, certain forms of color blindness can progress to legal blindness, i.e., an acuity of 6/60 (20/200) or worse, and often leave a person with complete blindness.

Color blindness always pertains to the cone photoreceptors in retinas, as the cones are capable of detecting the color frequencies of light.

About 8 percent of males, and 0.6 percent of females, are red-green color blind in some way or another, whether it is one color, a color combination, or another mutation. The reason males are at a greater risk of inheriting an X linked mutation is that males only have one X chromosome (XY, with the Y chromosome carrying altogether different genes than the X chromosome), and females have two (XX); if a woman inherits a normal X chromosome in addition to the one that carries the mutation, she will not display the mutation. Men do not have a second X chromosome to override the chromosome that carries the mutation. If 8% of variants of a given gene are defective, the probability of a single copy being defective is 8%, but the probability that two copies are both defective is 0.08 × 0.08 = 0.0064, or just 0.64%.

Types

Based on clinical appearance, color blindness may be described as total or partial. Total color blindness is much less common than partial color blindness. There are two major types of color blindness: those who have difficulty distinguishing between red and green, and who have difficulty distinguishing between blue and yellow.

Immunofluorescent imaging is a way to determine red–green color coding. Conventional color coding is difficult for individuals with red–green color blindness (protanopia or deuteranopia) to discriminate. Replacing red with magenta or green with turquoise improves visibility for such individuals.

The different kinds of inherited color blindness result from partial or complete loss of function of one or more of the different cone systems. When one cone system is compromised, dichromacy results. The most frequent forms of human color blindness result from problems with either the middle or long wavelength sensitive cone systems, and involve difficulties in discriminating reds, yellows, and greens from one another. They are collectively referred to as “red–green color blindness”, though the term is an over-simplification and is somewhat misleading. Other forms of color blindness are much more rare. They include problems in discriminating blues from greens and yellows from reds/pinks, and the rarest forms of all, complete color blindness or monochromacy, where one cannot distinguish any color from grey, as in a black-and-white movie or photograph.

Protanopes, deuteranopes, and tritanopes are dichromats; that is, they can match any color they see with some mixture of just two primary colors (whereas normally humans are trichromats and require three primary colors). These individuals normally know they have a color vision problem and it can affect their lives on a daily basis. Two percent of the male population exhibit severe difficulties distinguishing between red, orange, yellow, and green. A certain pair of colors, that seem very different to a normal viewer, appear to be the same color (or different shades of same color) for such a dichromat. The terms protanopia, deuteranopia, and tritanopia come from Greek and literally mean “inability to see (anopia) with the first (prot-), second (deuter-), or third (trit-) [cone]”, respectively.

Anomalous trichromacy is the least serious type of color deficiency. People with protanomaly, deuteranomaly, or tritanomaly are trichromats, but the color matches they make differ from the normal. They are called anomalous trichromats. In order to match a given spectral yellow light, protanomalous observers need more red light in a red/green mixture than a normal observer, and deuteranomalous observers need more green. From a practical standpoint though, many protanomalous and deuteranomalous people have very little difficulty carrying out tasks that require normal color vision. Some may not even be aware that their color perception is in any way different from normal.

Protanomaly and deuteranomaly can be diagnosed using an instrument called an anomaloscope, which mixes spectral red and green lights in variable proportions, for comparison with a fixed spectral yellow. If this is done in front of a large audience of males, as the proportion of red is increased from a low value, first a small proportion of the audience will declare a match, while most will see the mixed light as greenish; these are the deuteranomalous observers. Next, as more red is added the majority will say that a match has been achieved. Finally, as yet more red is added, the remaining, protanomalous, observers will declare a match at a point where normal observers will see the mixed light as definitely reddish.

Red–green color blindness

Protanopia, deuteranopia, protanomaly, and deuteranomaly are commonly inherited forms of red–green color blindness which affect a substantial portion of the human population. Those affected have difficulty with discriminating red and green hues due to the absence or mutation of the red or green retinal photoreceptors. It is sex-linked: genetic red–green color blindness affects males much more often than females, because the genes for the red and green color receptors are located on the X chromosome, of which males have only one and females have two. Females (46, XX) are red–green color blind only if both their X chromosomes are defective with a similar deficiency, whereas males (46, XY) are color blind if their single X chromosome is defective.

The gene for red–green color blindness is transmitted from a color blind male to all his daughters who are heterozygote carriers and are usually unaffected. In turn, a carrier woman has a fifty percent chance of passing on a mutated X chromosome region to each of her male offspring. The sons of an affected male will not inherit the trait from him, since they receive his Y chromosome and not his (defective) X chromosome. Should an affected male have children with a carrier or colorblind woman, their daughters may be colorblind by inheriting an affected X chromosome from each parent.

Because one X chromosome is inactivated at random in each cell during a woman’s development, deuteranomalous heterozygotes (i.e. female carriers of deuteranomaly) are potentially tetrachromats, because they will have the normal long wave (red) receptors, the normal medium wave (green) receptors, the abnormal medium wave (deuteranomalous) receptors and the normal autosomal short wave (blue) receptors in their retinas. The same applies to the carriers of protanomaly (who have two types of short wave receptors, normal medium wave receptors, and normal autosomal short wave receptors in their retinas). If, by chance, a woman is heterozygous for both protanomaly and deuteranomaly she could be pentachromatic. This situation could arise if, for instance, she inherited the X chromosome with the abnormal long wave gene (but normal medium wave gene) from her mother who is a carrier of protanomaly, and her other X chromosome from a deuteranomalous father. Such a woman would have a normal and an abnormal long wave receptor, a normal and abnormal medium wave receptor, and a normal autosomal short wave receptor – 5 different types of color receptors in all. The degree to which women who are carriers of either protanomaly or deuteranomaly are demonstrably tetrachromatic and require a mixture of four spectral lights to match an arbitrary light is very variable. In many cases it is almost unnoticeable, but in a minority the tetrachromacy is very pronounced. However, Jameson et al. have shown that with appropriate and sufficiently sensitive equipment all female carriers of red-green color blindness (i.e. heterozygous protanomaly, or heterozygous deuteranomaly) are tetrachromats to a greater or lesser extent.

Since deuteranomaly is by far the most common form of red-green blindness among men of northwestern European descent (with an incidence of 8%), then the carrier frequency (and of potential deuteranomalous tetrachromacy) among the females of that genetic stock is 14.7% (= [92% x 8%] x 2).

Blue–yellow color blindness

Those with tritanopia and tritanomaly have difficulty discriminating between bluish and greenish hues, as well as yellowish and reddish hues.

Color blindness involving the inactivation of the short-wavelength sensitive cone system (whose absorption spectrum peaks in the bluish-violet) is called tritanopia or, loosely, blue–yellow color blindness. The tritanope’s neutral point occurs near a yellowish 570 nm; green is perceived at shorter wavelengths and red at longer wavelengths. Mutation of the short-wavelength sensitive cones is called tritanomaly. Tritanopia is equally distributed among males and females. Jeremy H. Nathans (with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute) demonstrated that the gene coding for the blue receptor lies on chromosome 7, which is shared equally by males and females. Therefore, it is not sex-linked. This gene does not have any neighbor whose DNA sequence is similar. Blue color blindness is caused by a simple mutation in this gene.

Total color blindness

Total color blindness is defined as the inability to see color. Although the term may refer to acquired disorders such as cerebral achromatopsia also known as color agnosia, it typically refers to congenital color vision disorders (i.e. more frequently rod monochromacy and less frequently cone monochromacy).

In cerebral achromatopsia, a person cannot perceive colors even though the eyes are capable of distinguishing them. Some sources do not consider these to be true color blindness, because the failure is of perception, not of vision. They are forms of visual agnosia.

Monochromacy is the condition of possessing only a single channel for conveying information about color. Monochromats possess a complete inability to distinguish any colors and perceive only variations in brightness. It occurs in two primary forms:

Mechanism

The typical human retina contains two kinds of light cells: the rod cells (active in low light) and the cone cells (active in normal daylight). Normally, there are three kinds of cone cells, each containing a different pigment, which are activated when the pigments absorb light. The spectral sensitivities of the cones differ; one is most sensitive to short wavelengths, one to medium wavelengths, and the third to medium-to-long wavelengths within the visible spectrum, with their peak sensitivities in the blue, green, and yellow-green regions of the spectrum, respectively. The absorption spectra of the three systems overlap, and combine to cover the visible spectrum. These receptors are known as short (S), medium (M), and long (L) wavelength cones, but are also often referred to as blue, green, and red cones, although this terminology is inaccurate.

The receptors are each responsive to a wide range of wavelengths. For example, the long wavelength “red” receptor has its peak sensitivity in the yellow-green, some way from the red end (longest wavelength) of the visible spectrum. The sensitivity of normal color vision actually depends on the overlap between the absorption ranges of the three systems: different colors are recognized when the different types of cone are stimulated to different degrees. Red light, for example, stimulates the long wavelength cones much more than either of the others, and reducing the wavelength causes the other two cone systems to be increasingly stimulated, causing a gradual change in hue.

Many of the genes involved in color vision are on the X chromosome, making color blindness much more common in males than in females because males only have one X chromosome, while females have two. Because this is an X-linked trait, an estimated 2–3% of women have a 4th color cone and can be considered tetrachromats. One such woman has been reported to be a true or functional tetrachromat, as she can discriminate colors most other people can’t.

Diagnosis

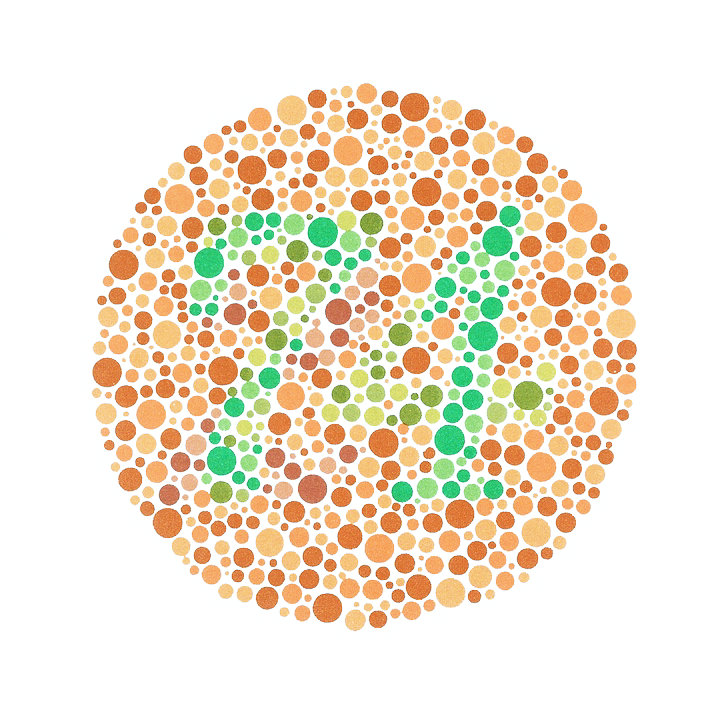

The Ishihara color test, which consists of a series of pictures of colored spots, is the test most often used to diagnose red–green color deficiencies. A figure (usually one or more Arabic digits) is embedded in the picture as a number of spots in a slightly different color, and can be seen with normal color vision, but not with a particular color defect. The full set of tests has a variety of figure/background color combinations, and enable diagnosis of which particular visual defect is present. The anomaloscope, described above, is also used in diagnosing anomalous trichromacy.

Position yourself about 75cm from your monitor so that the colour test image you are looking at is at eye level, read the description of the image and see what you can see!! It is not necessary in all cases to use the entire set of images. In a large scale examination the test can be simplified to six tests; test, one of tests 2 or 3, one of tests 4, 5, 6, or 7, one of tests 8 or 9, one of tests 10, 11, 12, or 13 and one of tests 14 or 15.[this quote needs a citation]

Because the Ishihara color test contains only numerals, it may not be useful in diagnosing young children, who have not yet learned to use numbers. In the interest of identifying these problems early on in life, alternative color vision tests were developed using only symbols (square, circle, car).

Besides the Ishihara color test, the US Navy and US Army also allow testing with the Farnsworth Lantern Test. This test allows 30% of color deficient individuals, whose deficiency is not too severe, to pass.

Another test used by clinicians to measure chromatic discrimination is the Farnsworth-Munsell 100 hue test. The patient is asked to arrange a set of colored caps or chips to form a gradual transition of color between two anchor caps.

The HRR color test (developed by Hardy, Rand, and Rittler) is a red–green color test that, unlike the Ishihara, also has plates for the detection of the tritan defects.

Most clinical tests are designed to be fast, simple, and effective at identifying broad categories of color blindness. In academic studies of color blindness, on the other hand, there is more interest in developing flexible tests to collect thorough datasets, identify copunctal points, and measure just noticeable differences.

Management

There is generally no treatment to cure color deficiencies. ″The American Optometric Association reports a contact lens on one eye can increase the ability to differentiate between colors, though nothing can make you truly see the deficient color.″

Lenses

Optometrists can supply colored spectacle lenses or a single red-tint contact lens to wear on the non-dominant eye, but although this may improve discrimination of some colors, it can make other colors more difficult to distinguish. A 1981 review of various studies to evaluate the effect of the X-chrom contact lens concluded that, while the lens may allow the wearer to achieve a better score on certain color vision tests, it did not correct color vision in the natural environment. A case history using the X-Chrom lens for a rod monochromat is reported and an X-Chrom manual is online.

Lenses that filter certain wavelengths of light can allow people with a cone anomaly, but not dichromacy, to see better separation of colors, especially those with classic “red/green” color blindness. They work by notching out wavelengths that strongly stimulate both red and green cones in a deuter- or protanomalous person, improving the distinction between the two cones’ signals. As of 2013, sunglasses that notch out color wavelengths are available commercially.

Apps

Many applications for iPhone and iPad have been developed to help colorblind people to view the colors in a better way. Many applications launch a sort of simulation of colorblind vision to make normal-view people understand how the color-blinds see the world. Others allow a correction of the image grabbed from the camera with a special “daltonizer” algorithm.

Epidemiology

Color blindness affects a large number of individuals, with protanopia and deuteranopia being the most common types. In individuals with Northern European ancestry, as many as 8 percent of men and 0.4 percent of women experience congenital color deficiency.

The number affected varies among groups. Isolated communities with a restricted gene pool sometimes produce high proportions of color blindness, including the less usual types. Examples include rural Finland, Hungary, and some of the Scottish islands. In the United States, about 7 percent of the male population—or about 10.5 million men—and 0.4 percent of the female population either cannot distinguish red from green, or see red and green differently from how others do (Howard Hughes Medical Institute, 2006 ). More than 95 percent of all variations in human color vision involve the red and green receptors in male eyes. It is very rare for males or females to be “blind” to the blue end of the spectrum.

Source From Wikipedia