The Department of Egyptian Antiquities of the Louvre is a department of the Louvre that is responsible for artifacts from the Nile civilizations which date from 4,000 BC to the 4th century. The collection, comprising over 50,000 pieces, is among the world’s largest, overviews Egyptian life spanning Ancient Egypt, the Middle Kingdom, the New Kingdom, Coptic art, and the Roman, Ptolemaic, and Byzantine periods. The Department of Egyptian Antiquities of the Louvre Museum maintains one of the world’s main Egyptological collections outside Egyptian territory, along with the Egyptian Museum of Turin and the British Museum and, in Egypt, the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

The department’s origins lie in the royal collection, but it was augmented by Napoleon’s 1798 expeditionary trip with Dominique Vivant, the future director of the Louvre. After Jean-François Champollion translated the Rosetta Stone, Charles X decreed that an Egyptian Antiquities department be created. Champollion advised the purchase of three collections, formed by Edmé-Antoine Durand, Henry Salt and Bernardino Drovet; these additions added 7,000 works. Growth continued via acquisitions by Auguste Mariette, founder of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. Mariette, after excavations at Memphis, sent back crates of archaeological finds including The Seated Scribe.

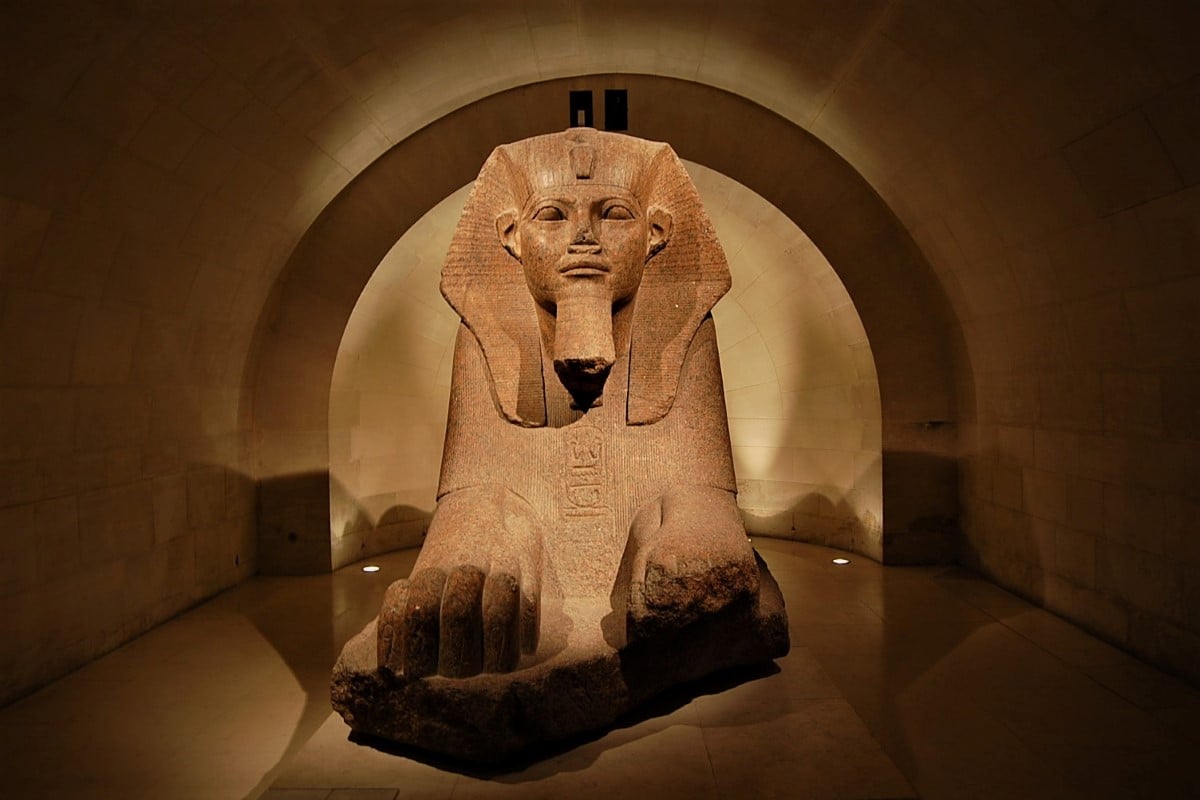

Guarded by the Large Sphinx (c. 2000 BC), the collection is housed in around 30 rooms. Holdings include art, papyrus scrolls, mummies, tools, clothing, jewelry, games, musical instruments, and weapons. Pieces from the ancient period include the Gebel el-Arak Knife from 3400 BC, The Seated Scribe, and the Head of King Djedefre. Middle Kingdom art, “known for its gold work and statues”, moved from realism to idealization; this is exemplified by the schist statue of Amenemhatankh and the wooden Offering Bearer. The New Kingdom and Coptic Egyptian sections are deep, but the statue of the goddess Nephthys and the limestone depiction of the goddess Hathor demonstrate New Kingdom sentiment and wealth.

History

In 1826, Charles X made Jean-François Champollion, decipherer of Egyptian hieroglyphics, the first curator of what was then called the Egyptian Museum. This section of the Charles X Museum is located on the first floor of the Cour Carrée, in the South wing. The four rooms are fitted out with the help of the architect Pierre François Léonard Fontaine. The first two rooms illustrate funerary customs, the third is the civil room, the fourth is the room of the gods. The paintings of the ceilings are due to François Édouard Picot (The Study and the Genius of the arts revealing Egypt to Greece) and Abel de Pujol(Egypt saved by Joseph).

The moment when Egyptology was born, in this first quarter of the 19th century, was a period of great change for the Louvre. Over the course of the different political regimes, its status oscillates between royal (or imperial) residence and museum. In the years 1820-1830, the museum gained ground on the palace. The enrichment of the collections leads to the opening of new sections like so many independent museums inside the same gigantic building. This is how the Angoulême gallery came into being with sculptures from the Renaissance and Modern Times, the Marine Museum, the Assyrian Museum and the Charles X Museum.

To accommodate this new section within the Louvre, a row of 9 rooms was chosen, on the first floor on the Seine side, today the Sully wing. This part of the palace had first housed the apartments of the queens of France, then the Royal Academy of Architecture, and finally the collections of Antiques.

On the death of Champollion inmars 1832, three large rooms are added to the ground floor for the department. Under Philippe-Auguste Jeanron, the museum underwent an ambitious program of reorganization. This necessarily affected the Egyptian department, in particular with the addition of a monumental gallery for large stone monuments (inaugurated injune 1849) and with the modification of the rooms on the first floor. A fifth room, for example, is being opened, the historical room. The Hall of Columns, on the first floor, was assigned to the Egyptian department in 1864. In 1895, it was the turn of the gallery of Algiers, where the stelae were placed. The Henri IV gallery will follow.

In 1902, there were four large rooms on the first floor completely remodeled. The first floor landing precedes a first room on funerary furniture. Then come a room of industrial art objects, a room of figurative monuments, and a room of bronzes and jewelry. February 21, 1905, an annex of the department will be inaugurated in the pavilion of the States. Thus, in 1905, by the considerable enrichments experienced by the department, the collections were completely split up across the museum.

Under Henri Verne, with the Verne plan drawn up in 1929, the Egyptian department was particularly favoured. In general, it is a matter of occupying available or poorly allocated premises to regroup the dispersed sections. Thus, all the rooms on the ground floor, between the Arts desk and the Midi pavilion, are allocated to it, which doubles its surface area. Added to this is the digging of two crypts under the counters.

The redevelopment was completed in 1938. A vestibule (where the mastaba of Akhethetep is located) and six rooms arranged chronologically are opened to the public on the first floor. In 1948, additional spaces were inaugurated, the Salle Clarac and the Salle des Colonnes. September 24, 1981, with the allocation of the Richelieu wing to the museum, Egyptian antiquities now occupy the entire east wing of the Cour Carrée (ground floor and first floor).

For this decoration of the Charles X museum which still exists today, the architects Charles Percier and Pierre Fontaine were called upon. They have been working on the transformations of the Louvre for more than twenty years. They create a harmonious row. The rooms are connected by high openings that evoke triumphal arches. Stucco imitates pink or white marble. The gilding emphasizes the architecture. The windows are still the original ones.

The decorations of the ceilings are entrusted to the greatest painters of the time such as Antoine-Jean Gros, Horace Vernet or Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. If the general theme is Antiquity, the sources of inspiration are very diverse: Egypt, Greece, Rome, but also works of art from the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. What is staged allegorically by the artists is precisely the vision that we had of Pharaonic Egypt, through the two prisms of Greco-Roman Antiquity and the Bible. We can thus see The Study and the Genius revealing ancient Egypt to Greece, or even Egypt saved by Joseph.

Since Champollion, knowledge of Egyptian Antiquity has evolved considerably, and the collections have grown. Now they span two floors. You can see several of the objects that were key to understanding this civilization, some of which were acquired by Champollion himself. This is the case of the colossal statues of Ramses II, the cup of Djéhouty, or the relief of the tomb of Seti I. As for the rooms of the Charles X Museum, they are now shared between the end of the Egyptian chronological journey and the collections of Greek antiquities.

Among all the ceilings of the Charles X museum, The Apotheosis of Homer by the French painter Ingres has become a real museum painting. It is said that Charles X had forgotten to raise his head to admire it during the inauguration of the museum. The work is then taken down and replaced on the ceiling by a copy. The original is exhibited in the red rooms devoted to great French painting of the 19th century.

This heavy pendant is a masterpiece of Egyptian goldsmithing. It is made up of the three deities of one of the major triads of Egyptian mythology: the god Osiris, squatting on his base in the center and flanked by the goddess Isis, his wife, and their son and heir, Horus. It is a concentrate of one of the fundamental myths of Egyptian religion: Osiris, killed by his brother Seth, is resuscitated by his wife Isis who gives birth to Horus, the falcon god. The latter avenges his father and ascends the throne. By symbolizing the victory over the evil forces, it ensures the sustainability of pharaonic royalty.

Collection

The collection covers all eras of ancient Egyptian civilization, from the time of Nagada to Roman and Coptic Egypt. Currently, Egyptian Antiquities are spread over three floors of the Sully wing of the museum, over some thirty rooms in total: on the mezzanine floor, we find Roman Egypt and Coptic Egypt; on the ground floor and on the first floor, Pharaonic Egypt.

The Egyptian collections extend over 2 floors. On the first, a presentation of the daily life of the Egyptians through thematic rooms, on the second, a chronological presentation of ancient Egypt from the predynastic period to the Ptolemaic period. The rooms of the Charles X Museum notably host the end of the chronological presentation of the Louvre’s Egyptian Antiquities: the New Empire, the Third Intermediate Period, the Late Period and the Ptolemaic Period.

A strange creature, half human half animal, seems to guard the entrance to the Egyptian collections. From the depths of its crypt, the body of a lion and the face of a king, the great sphinx of Tanis welcomes the visitor with its enigmatic figure. It announces a vast journey of more than 6,000 works covering nearly 5,000 years of Egyptian history.

On the ground floor of the Sully wing, nineteen rooms make up the thematic route. On the first floor of the Sully wing, eleven rooms make up the chronological itinerary, with a division between the space for showcasing major works and denser study galleries.

The first rooms evoke the major aspects of Egyptian civilization such as the importance of the Nile and its annual flood which allows agriculture. The chapel of the mastaba of Akhethotep makes it possible to see the monumentality of Egyptian architecture. A room is devoted to hieroglyphs and then we discover the daily life of the Egyptians, their crafts, their furniture, their ornaments and their clothes. The temple hall, then the collection of sarcophagi, recall the central place of religion and funerary rites in Egyptian civilization.

On the first floor, a historical and artistic approach to this civilization is offered. This time, it’s about discovering the chronological evolution of Egyptian art over nearly 5000 years. The visitor notably crosses the famous gaze of the Crouching Scribe or can admire the statues of kings and queens such as Sesostris III, Ahmes Nefertari, Hatshepsout, Amenophis III, Nefertiti and Akhenaten or Ramses II.

Egypt is known to us today, largely thanks to its tombs, their decoration and their furniture. Under the Old Kingdom (2700-2200 BC), the king’s entourage was authorized to build rich burials called mastaba. These massive buildings include a burial chamber at the bottom of a well where the mummy of the deceased is placed in its sarcophagus. Above this well, in the superstructure, is a chapel in which the funerary cult was carried out.

Purchased from the Egyptian government in 1903, the mastaba chapel of a certain Akhethetep was rebuilt stone by stone in the museum. Inside, we discover the bas-reliefs painted and captioned with hieroglyphic inscriptions. A veritable mine of information on the daily life of the ancient Egyptians, peasant life in the Nile Valley, field work according to the seasons.

Predynastic Period and Thinite Period

Among the most famous exhibits are the Gebel el-Arak knife and the hunting palette from the Nagada period. The major piece illustrating the art of the Thinite era is the Serpent-King Stela.

Old Kingdom

The art of the Old Kingdom includes masterpieces such as the three statues of Sepa and his wife Nesa dating from the Third Dynasty, the famous Crouching Scribe, probably dating from the Fourth Dynasty, as well as the painted limestone statuette representing Raherka and his wife Merseânkh. The chapel of the mastaba of Akhethotep, dismantled from its original site at Saqqara and reassembled in one of the rooms on the ground floor, is an example of funerary architecture dating from the Fifth Dynasty.

Middle Kingdom

The Middle Kingdom extends from around -2033 to -1786, corresponding to the XI th dynasty (-2106 to -1963), which saw the country reunified around -2033 by Montouhotep II and to the XII th dynasty (-1963 to -1786), golden age of the Middle Kingdom.

This period is mainly represented in the Louvre by works dating from the XII th dynasty: a large wooden statue representing Chancellor Nakht and his sarcophagus; an offering bearer in stuccoed and painted wood; a large hollow-carved limestone door lintel from the temple of Montu in Médamoud; the sphinx of Amenemhat II.

New Kingdom

For the New Empire, we note the bust of Akhenaton dating from the XVIII th dynasty as well as the polychrome statuette representing him and his wife Nefertiti, works illustrating the particularities of Amarna art; there are also several major works of the 19th and 20th dynasties (which are those of the Ramessides) with in particular the painted relief representing Hathor welcoming Seti I and coming from the tomb of the pharaoh in the Valley of the Kings, the horse ring and the basin of the sarcophagus of Ramses III.

Ptolemaic and Roman Egypt

From the Late Period and the Ptolemaic period, the museum exhibits in particular the pendant of Osorkon II, a masterpiece of ancient goldsmithing; the statuette of Taharqa and the god Hémen (bronze, greywacke and gold); the bronze statuette with inlays representing the divine worshiper of Amon Karomama; a bronze statue of Horus; the Dendera zodiac, as well as several Fayoum portraits from Roman times.

Among the sarcophagi on display is that of Dioscorides, a Greek general in the time of Ptolemy VI, who chose to be buried according to ancient Egyptian customs.

Highlights

Currently, Egyptian Antiquities are spread over three floors: on the mezzanine, Roman Egypt and Coptic Egypt; on the ground floor and on the first floor, Pharaonic Egypt. Among the most famous exhibits are the Gebel el-Arak knife and the hunting palette from the Nagada period. The major piece illustrating the art of the Thinite period is the stele of the Serpent King. The art of the Old Kingdom includes masterpieces such as the three statues of Sepa and his wife Nesa dating from the Third Dynasty, The Crouching Scribe, probably dating from the Fourth Dynasty, just like the painted limestone statuette representing Raherka and his wife Merseankh. The Mastaba Chapel of Akhethotep, dismantled from its original site atSaqqara and reassembled in one of the rooms on the ground floor, is an example of funerary architecture dating from the 5th dynasty.

For the Middle Kingdom, there is the large wooden statue representing the Chancellor Nakhti as well as his sarcophagus, a very beautiful carrier of offerings in stuccoed and painted wood, a large door lintel in limestone carved in relief in the hollow and coming from the temple of Montou at Médamoud, the sphinx of Amenemhat II (works all dating from the XII th dynasty).

For the New Empire, we note the bust of Akhenaton dating from the XVIII th dynasty as well as the polychrome statuette representing him with his wife Nefertiti, works illustrating the particularities of Amarna art; there are also several major works of the 19th and 20th dynasties (which are those of the Ramessides) with in particular the painted relief representing Hathor welcoming Seti I and coming from the tomb of the pharaoh in the Valley of the Kings, the horse ring and the basin of the sarcophagus of Ramses III.

From the Late Period and the Ptolemaic period, the museum exhibits in particular the pendant with the name of Osorkon II, a masterpiece of ancient goldsmithery, the statuette of Taharqa and the god Hémen (bronze, greywacke and gold), the bronze statuette with inlays representing the divine worshiper of Amon Karomama, a bronze statue of Horus, the famous zodiac of Dendera as well as several portraits of the Fayoum from the Roman.

Louvre Museum

The Louvre is the world’s most-visited museum, and a historic landmark in Paris, France. The Louvre Museum is a Parisian art and archeology museum housed in the former royal palace of the Louvre. Opened in 1793, it is one of the largest and richest museums in the world, but also the busiest with nearly 9 million visitors a year. It is the home of some of the best-known works of art, including the Mona Lisa and the Venus de Milo.

The museum is housed in the Louvre Palace, originally built in the late 12th to 13th century under Philip II. Remnants of the Medieval Louvre fortress are visible in the basement of the museum. Due to urban expansion, the fortress eventually lost its defensive function, and in 1546 Francis I converted it into the primary residence of the French Kings. The building was extended many times to form the present Louvre Palace.

The Musée du Louvre contains more than 380,000 objects and displays 35,000 works of art in eight curatorial departments with more than 60,600 square metres (652,000 sq ft) dedicated to the permanent collection. The Louvre exhibits sculptures, objets d’art, paintings, drawings, and archaeological finds. The Louvre Museum presents very varied collections, with a large part devoted to the art and civilizations of Antiquity: Mesopotamia, Egypt, Greece and RomeLogo indicating tariffs to quote that they; medieval Europe (setting around the ruins of the keep of Philippe-Auguste, on which the Louvre was built) and Napoleonic France are also widely represented.

The Louvre has a long history of artistic and historical conservation, from the Ancien Régime to the present day. Following the departure of Louis XIV for the Palace of Versailles at the end of the 17th century century, part of the royal collections of paintings and antique sculptures are stored there. After having housed several academies for a century, including that of painting and sculpture, as well as various artists housed by the king, the former royal palace was truly transformed during the Revolution into a “Central Museum of the Arts of the Republic”. It opened in 1793, exhibiting around 660 works, mainly from royal collections or confiscated from emigrant nobles or from churches. Subsequently, the collections will continue to be enriched by wartime spoils, acquisitions, sponsorships, legacies, donations, and archaeological discoveries.

Located in the 1st arrondissement of Paris, between the right bank of the Seine and the rue de Rivoli, the museum is distinguished by the glass pyramid of its reception hall, erected in 1989 in the Napoleon courtyard and which has become emblematic, while the equestrian statue of Louis XIV constitutes the starting point of the Parisian historical axis. Among his most famous plays are The Mona Lisa, The Venus de Milo, The Crouching Scribe, The Victory of Samothrace, and The Code of Hammurabi.