Well-founded phenomena, in the philosophy of Gottfried Leibniz, are ways in which the world falsely appears to us, but which are grounded in the way the world is (as opposed to dreams or hallucinations, which are false appearances that are not thus grounded).

For Leibniz, the universe is made up of an infinite number of simple substances or monads, each of which contains a representation of the entire universe (past, present, and future), and which are all causally isolated from one another (“Monads have no windows through which anything could enter or depart.”[1]) For the most part the monads’ perceptions are more or less confused and obscure, but some of them correspond either to the ways in which other monads are related or to the ways that the representation is genuinely ordered; these are the well-founded phenomena.

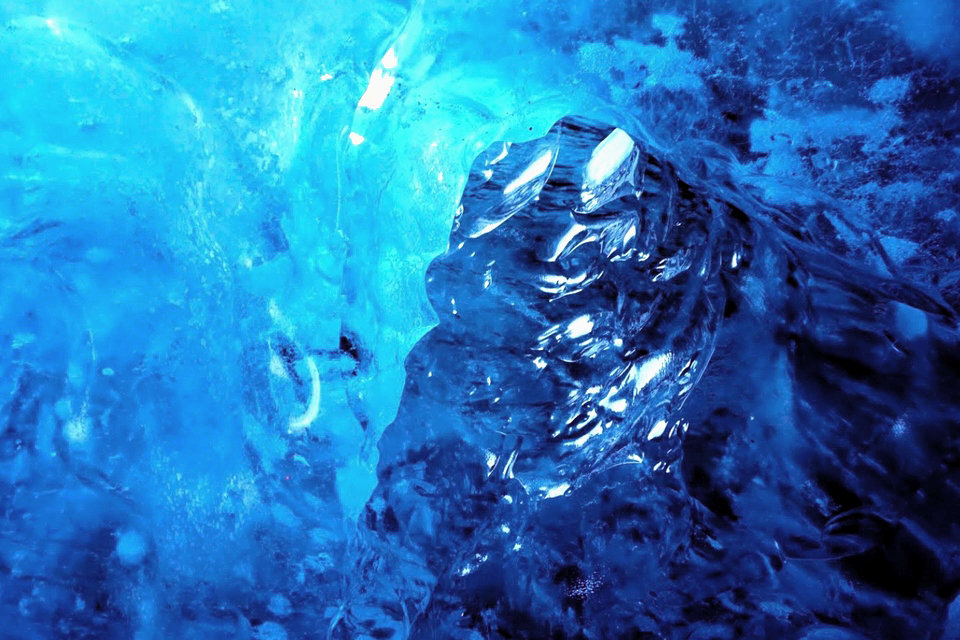

In the world of ordinary experience we might call a rainbow a well-ordered phenomenon; it appears to us to be a coloured arch in the sky, though there is in fact no arch there. We are not suffering from hallucinations, though, for the appearance is grounded in the way the world is ordered – in the behaviour of light, dust motes, water particles, etc.

For Leibniz, there are two main categories of well-founded phenomena: the ordinary world of individual objects and their interactions, and more abstract phenomena such as space, time, and causality. This is also found in his expression of pre-established harmony being the basis of causation.