With the rise of the European Academies, most notably the Académie française which held a central role in Academic art, still life began to fall from favor. The Academies taught the doctrine of the “Hierarchy of genres” (or “Hierarchy of Subject Matter”), which held that a painting’s artistic merit was based primarily on its subject. In the Academic system, the highest form of painting consisted of images of historical, Biblical or mythological significance, with still-life subjects relegated to the very lowest order of artistic recognition. Instead of using still life to glorify nature, some artists, such as John Constable and Camille Corot, chose landscapes to serve that end.

When Neoclassicism started to go into decline by the 1830s, genre and portrait painting became the focus for the Realist and Romantic artistic revolutions. Many of the great artists of that period included still life in their body of work. The still-life paintings of Francisco Goya, Gustave Courbet, and Eugène Delacroix convey a strong emotional current, and are less concerned with exactitude and more interested in mood. Though patterned on the earlier still-life subjects of Chardin, Édouard Manet’s still-life paintings are strongly tonal and clearly headed toward Impressionism. Henri Fantin-Latour, using a more traditional technique, was famous for his exquisite flower paintings and made his living almost exclusively painting still life for collectors.

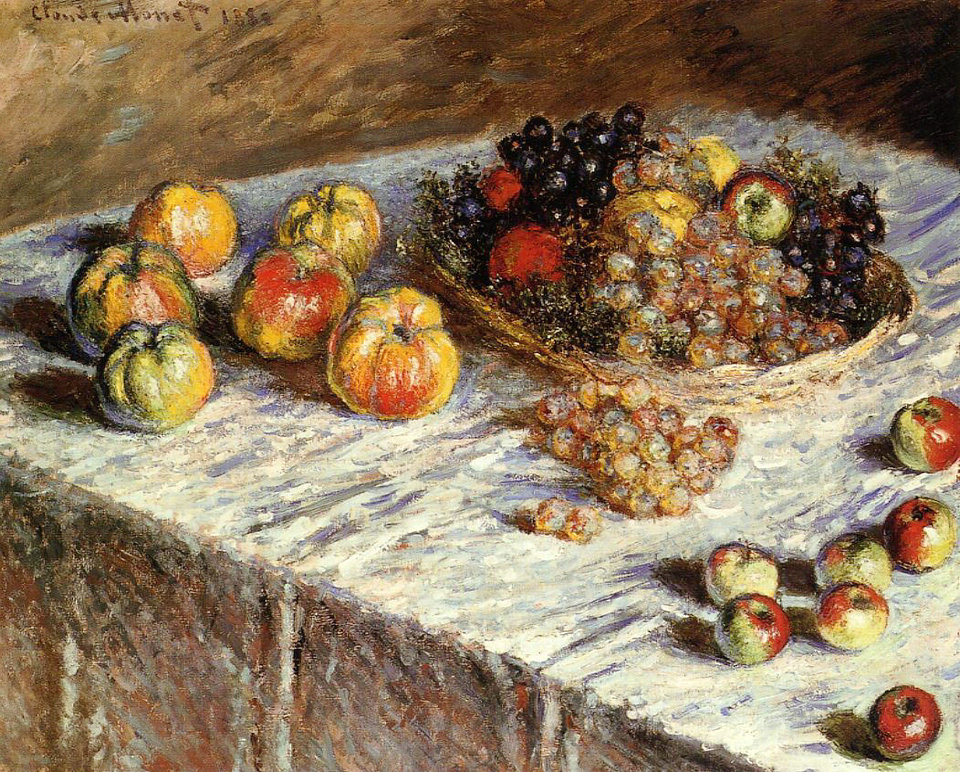

However, it was not until the final decline of the Academic hierarchy in Europe, and the rise of the Impressionist and Post-Impressionist painters, that technique and colour harmony triumphed over subject matter, and that still life was once again avidly practiced by artists. In his early still life, Claude Monet shows the influence of Fantin-Latour, but is one of the first to break the tradition of the dark background, which Pierre-Auguste Renoir also discards in Still Life with Bouquet and Fan (1871), with its bright orange background. With Impressionist still life, allegorical and mythological content is completely absent, as is meticulously detailed brush work. Impressionists instead focused on experimentation in broad, dabbing brush strokes, tonal values, and colour placement. The Impressionists and Post-Impressionists were inspired by nature’s colour schemes but reinterpreted nature with their own colour harmonies, which sometimes proved startlingly unnaturalistic. As Gauguin stated, “Colours have their own meanings.” Variations in perspective are also tried, such as using tight cropping and high angles, as with Fruit Displayed on a Stand by Gustave Caillebotte, a painting which was mocked at the time as a “display of fruit in a bird’s-eye view.”

Vincent van Gogh’s “Sunflowers” paintings are some of the best-known 19th-century still-life paintings. Van Gogh uses mostly tones of yellow and rather flat rendering to make a memorable contribution to still-life history. His Still Life with Drawing Board (1889) is a self-portrait in still-life form, with Van Gogh depicting many items of his personal life, including his pipe, simple food (onions), an inspirational book, and a letter from his brother, all laid out on his table, without his own image present. He also painted his own version of a vanitas painting Still Life with Open Bible, Candle, and Book (1885).

In the United States during Revolutionary times, American artists trained abroad applied European styles to American portrait painting and still life. Charles Willson Peale founded a family of prominent American painters, and as major leader in the American art community, also founded a society for the training of artists as well as a famous museum of natural curiosities. His son Raphaelle Peale was one of a group of early American still-life artists, which also included John F. Francis, Charles Bird King, and John Johnston. By the second half of the 19th century, Martin Johnson Heade introduced the American version of the habitat or biotope picture, which placed flowers and birds in simulated outdoor environments. The American trompe-l’œil paintings also flourished during this period, created by John Haberle, William Michael Harnett, and John Frederick Peto. Peto specialized in the nostalgic wall-rack painting while Harnett achieved the highest level of hyper-realism in his pictorial celebrations of American life through familiar objects.

Francisco Goya, Still Life with Fruit, Bottles, Breads (1824–1826)

Nineteenth-century paintings

Eugène Delacroix, Still Life with Lobster and trophies of hunting and fishing (1826–1827), Louvre |

Gustave Caillebotte, (1848–1894), Yellow Roses in a Vase (1882), Dallas Museum of Art |

Henri Fantin-Latour, (1836–1904), White Roses, Chrysanthemums in a Vase, Peaches and Grapes on a Table with a White Tablecloth(1867) |

Paul Cézanne (1839–1906), The Black Marble Clock (1869–1871), private collection |

|---|---|---|---|

Mary Cassatt, (1844–1926), Lilacs in a Window (1880) |

Claude Monet (1840–1926), Still-Life with Apples and Grapes (1880), Art Institute of Chicago |

Édouard Manet (1832–1883), Carnations and Clematis in a Crystal Vase (1883), Musée d’Orsay, Paris |

Paul Gauguin, Still Life with Apples, a Pear, and a Ceramic Portrait Jug(1889), Fogg Museum, Cambridge, Massachusetts |

William Harnett (1848–1892), After the Hunt (1883) |

William Harnett (1848–1892), Still life violin and music (1888), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City |

Darius Cobb (1834–1919), a Civil War trompe l’oeil composition, here in a chromolithograph print |

Paul Cézanne, Still Life with Cherub(1895), Courtauld Institute Galleries, London |

A still life (plural: still lifes) is a work of art depicting mostly inanimate subject matter, typically commonplace objects which are either natural (food, flowers, dead animals, plants, rocks, shells, etc.) or man-made (drinking glasses, books, vases, jewelry, coins, pipes, etc.).

With origins in the Middle Ages and Ancient Greco-Roman art, still-life painting emerged as a distinct genre and professional specialization in Western painting by the late 16th century, and has remained significant since then. A still-life form gives the artist more freedom in the arrangement of elements within a composition than do paintings of other types of subjects such as landscape or portraiture. Still life, as a particular genre, began with Netherlandish painting of the 16th and 17th centuries, and the English term still life derives from the Dutch word stilleven. Early still-life paintings, particularly before 1700, often contained religious and allegorical symbolism relating to the objects depicted. Some modern still-life work breaks the two-dimensional barrier and employs three-dimensional mixed media, and uses found objects, photography, computer graphics, as well as video and sound.

The term includes the painting of dead animals, especially game. Live ones are considered animal art, although in practice they were often painted from dead models. The still-life category also shares commonalities with zoological and especially botanical illustration, where there has been considerable overlap among artists. Generally a still life includes a fully depicted background, and puts aesthetic rather than illustrative concerns as primary.

Still life occupied the lowest rung of the hierarchy of genres, but has been extremely popular with buyers. As well as the independent still-life subject, still-life painting encompasses other types of painting with prominent still-life elements, usually symbolic, and “images that rely on a multitude of still-life elements ostensibly to reproduce a ‘slice of life'”. The trompe-l’œil painting, which intends to deceive the viewer into thinking the scene is real, is a specialized type of still life, usually showing inanimate and relatively flat objects.

Source From Wikipedia