PAL color system

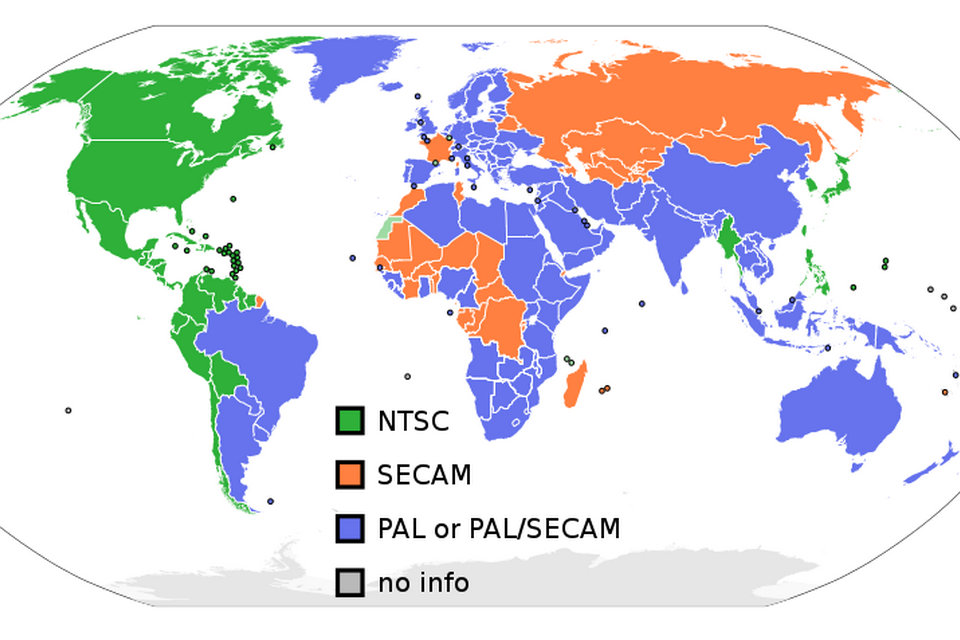

Phase Alternating Line (PAL) is a colour encoding system for analogue television used in broadcast television systems in most countries broadcasting at 625-line / 50 field (25 frame) per second (576i). Other common colour encoding systems are NTSC and SECAM.

All the countries using PAL are currently in process of conversion or have already converted standards to DVB, ISDB or DTMB.

This page primarily discusses the PAL colour encoding system. The articles on broadcast television systems and analogue television further describe frame rates, image resolution and audio modulation.

History

In the 1950s, the Western European countries started planning to introduce colour television, and were faced with the problem that the NTSC standard demonstrated several weaknesses, including colour tone shifting under poor transmission conditions, which became a major issue considering Europe’s geographical and weather-related particularities. To overcome NTSC’s shortcomings, alternative standards were devised, resulting in the development of the PAL and SECAM standards. The goal was to provide a colour TV standard for the European picture frequency of 50 fields per second (50 hertz), and finding a way to eliminate the problems with NTSC.

PAL was developed by Walter Bruch at Telefunken in Hanover, Germany, with important input from Dr. Kruse and Gerhard Mahler (de). The format was patented by Telefunken in 1962, citing Bruch as inventor, and unveiled to members of the European Broadcasting Union (EBU) on 3 January 1963. When asked, why the system was named “PAL” and not “Bruch” the inventor answered that a “Bruch system” would probably not have sold very well (“Bruch” lit. means “break”). The first broadcasts began in the United Kingdom in June 1967, followed by West Germany late that year. The one BBC channel initially using the broadcast standard was BBC2, which had been the first UK TV service to introduce “625-lines” in 1964. Telefunken PALcolor 708T was the first PAL commercial TV set. It was followed by Loewe-Farbfernseher S 920 & F 900.

Telefunken was later bought by the French electronics manufacturer Thomson. Thomson also bought the Compagnie Générale de Télévision where Henri de France developed SECAM, the first European Standard for colour television. Thomson, now called Technicolor SA, also owns the RCA brand and licenses it to other companies; Radio Corporation of America, the originator of that brand, created the NTSC colour TV standard before Thomson became involved.

The term PAL was often used informally and somewhat imprecisely to refer to the 625-line/50 Hz (576i) television system in general, to differentiate from the 525-line/60 Hz (480i) system generally used with NTSC. Accordingly, DVDs were labelled as PAL or NTSC (referring to the line count and frame rate) even though technically the discs carry neither PAL nor NTSC encoded signal. CCIR 625/50 and EIA 525/60 are the proper names for these (line count and field rate) standards; PAL and NTSC on the other hand are methods of encoding color information in the signal.

Colour encoding

Both the PAL and the NTSC system use a quadrature amplitude modulated subcarrier carrying the chrominance information added to the luminance video signal to form a composite video baseband signal. The frequency of this subcarrier is 4.43361875 MHz for PAL and NTSC 4.43, compared to 3.579545 MHz for NTSC 3.58. The SECAM system, on the other hand, uses a frequency modulation scheme on its two line alternate colour subcarriers 4.25000 and 4.40625 MHz.

The name “Phase Alternating Line” describes the way that the phase of part of the colour information on the video signal is reversed with each line, which automatically corrects phase errors in the transmission of the signal by cancelling them out, at the expense of vertical frame colour resolution. Lines where the colour phase is reversed compared to NTSC are often called PAL or phase-alternation lines, which justifies one of the expansions of the acronym, while the other lines are called NTSC lines. Early PAL receivers relied on the human eye to do that cancelling; however, this resulted in a comb-like effect known as Hanover bars on larger phase errors. Thus, most receivers now use a chrominance analog delay line, which stores the received colour information on each line of display; an average of the colour information from the previous line and the current line is then used to drive the picture tube. The effect is that phase errors result in saturation changes, which are less objectionable than the equivalent hue changes of NTSC. A minor drawback is that the vertical colour resolution is poorer than the NTSC system’s, but since the human eye also has a colour resolution that is much lower than its brightness resolution, this effect is not visible. In any case, NTSC, PAL, and SECAM all have chrominance bandwidth (horizontal colour detail) reduced greatly compared to the luminance signal.

The 4.43361875 MHz frequency of the colour carrier is a result of 283.75 colour clock cycles per line plus a 25 Hz offset to avoid interferences. Since the line frequency (number of lines per second) is 15625 Hz (625 lines × 50 Hz ÷ 2), the colour carrier frequency calculates as follows: 4.43361875 MHz = 283.75 × 15625 Hz + 25 Hz.

The original colour carrier is required by the colour decoder to recreate the colour difference signals. Since the carrier is not transmitted with the video information it has to be generated locally in the receiver. In order that the phase of this locally generated signal can match the transmitted information, a 10 cycle burst of colour subcarrier is added to the video signal shortly after the line sync pulse, but before the picture information, during the so-called back porch. This colour burst is not actually in phase with the original colour subcarrier, but leads it by 45 degrees on the odd lines and lags it by 45 degrees on the even lines. This swinging burst enables the colour decoder circuitry to distinguish the phase of the R-Y vector which reverses every line.

PAL vs. NTSC

PAL usually has 576 visible lines compared with 480 lines with NTSC, meaning that PAL has a 20% higher resolution, in fact it even has a higher resolution than Enhanced Definition standard (854×480). Most TV output for PAL and NTSC use interlaced frames meaning that even lines update on one field and odd lines update on the next field. Interlacing frames gives a smoother motion with half the frame rate. NTSC is used with a frame rate of 60i or 30p whereas PAL generally uses 50i or 25p; both use a high enough frame rate to give the illusion of fluid motion. This is due to the fact that NTSC is generally used in countries with a utility frequency of 60 Hz and PAL in countries with 50 Hz, although there are many exceptions. Both PAL and NTSC have a higher frame rate than film which uses 24 frames per second. PAL has a closer frame rate to that of film, so most films are sped up 4% to play on PAL systems, shortening the runtime of the film and, without adjustment, slightly raising the pitch of the audio track. Film conversions for NTSC instead use 3:2 pull down to spread the 24 frames of film across 60 interlaced fields. This maintains the runtime of the film and preserves the original audio, but may cause worse interlacing artifacts during fast motion.

NTSC receivers have a tint control to perform colour correction manually. If this is not adjusted correctly, the colours may be faulty. The PAL standard automatically cancels hue errors by phase reversal, so a tint control is unnecessary yet Saturation control can be more useful. Chrominance phase errors in the PAL system are cancelled out using a 1H delay line resulting in lower saturation, which is much less noticeable to the eye than NTSC hue errors.

However, the alternation of colour information—Hanover bars—can lead to picture grain on pictures with extreme phase errors even in PAL systems, if decoder circuits are misaligned or use the simplified decoders of early designs (typically to overcome royalty restrictions). In most cases such extreme phase shifts do not occur. This effect will usually be observed when the transmission path is poor, typically in built up areas or where the terrain is unfavourable. The effect is more noticeable on UHF than VHF signals as VHF signals tend to be more robust.

In the early 1970s some Japanese set manufacturers developed decoding systems to avoid paying royalties to Telefunken. The Telefunken license covered any decoding method that relied on the alternating subcarrier phase to reduce phase errors. This included very basic PAL decoders that relied on the human eye to average out the odd/even line phase errors. One solution was to use a 1H analog delay line to allow decoding of only the odd or even lines. For example, the chrominance on odd lines would be switched directly through to the decoder and also be stored in the delay line. Then, on even lines, the stored odd line would be decoded again. This method effectively converted PAL to NTSC. Such systems suffered hue errors and other problems inherent in NTSC and required the addition of a manual hue control.

PAL and NTSC have slightly divergent colour spaces, but the colour decoder differences here are ignored.

PAL vs. SECAM

The SECAM patents predate those of PAL by several years (1956 vs 1962). Its creator, Henri de France, in search of a response to known NTSC hue problems, came up with ideas that were to become fundamental to both European systems, namely: 1) colour information on two successive TV lines is very similar and vertical resolution can be halved without serious impact on perceived visual quality 2) more robust colour transmission can be achieved by spreading information on two TV lines instead of just one 3) information from the two TV lines can be recombined using a delay line.

SECAM applies those principles by transmitting alternately only one of the U and V components on each TV line, and getting the other from the delay line. QAM is not required, and frequency modulation of the subcarrier is used instead for additional robustness (sequential transmission of U and V was to be reused much later in Europe’s last “analog” video systems: the MAC standards).

SECAM is free of both hue and saturation errors. It is not sensitive to phase shifts between the color burst and the chrominance signal, and for this reason was sometimes used in early attempts at color video recording, where tape speed fluctuations could get the other systems into trouble. In the receiver, it did not require a quartz crystal (which was an expensive component at the time) and generally could do with lower accuracy delay lines and components.

SECAM transmissions are more robust over longer distances than NTSC or PAL. However, owing to their FM nature, the color signal remains present, although at reduced amplitude, even in monochrome portions of the image, thus being subject to stronger cross color.

One serious drawback for studio work is that the addition of two SECAM signals does not yield valid colour information, due to its use of frequency modulation. It was necessary to demodulate the FM and handle it as AM for proper mixing, before finally remodulating as FM, at the cost of some added complexity and signal degradation. In its later years, this was no longer a problem, due to the wider use of component and digital equipment.

PAL can work without a delay line, but this configuration, sometimes referred to as “poor man’s PAL”, could not match SECAM in terms of picture quality. To compete with it at the same level, it had to make use of the main ideas outlined above, and as a consequence PAL had to pay license fees to SECAM. Over the years, this contributed significantly to the estimated 500 million francs gathered by the SECAM patents (for an initial 100 million francs invested in research).

Hence, PAL could be considered as a hybrid system, with its signal structure closer to NTSC, but its decoding borrowing much from SECAM.

There were initial specifications to use color with the French 819 line format (system E). However, “SECAM E” only ever existed in development phases. Actual deployment used the 625 line format. This made for easy interchange and conversion between PAL and SECAM in Europe. Conversion was often not even needed, as more and more receivers and VCRs became compliant with both standards, helped in this by the common decoding steps and components. And furthermore, when the SCART plug became standard, it could take RGB as an input, effectively bypassing all the color coding formats’ peculiarities.

When it comes to home VCRs, all video standards use what is called “color under” format. Color is extracted from the high frequencies of the video spectrum, and moved to the lower part of the spectrum available from tape. Luminance then uses what remains of it, above the color frequency range. This is usually done by heterodyning for PAL (as well as NTSC). But the FM nature of color in SECAM allows for a cheaper trick: division by 4 of the subcarrier frequency (and multiplication on replay). This became the standard for SECAM VHS recording in France. Most other countries kept using the same heterodyning process as for PAL or NTSC and this is known as MESECAM recording (as it was more convenient for some Middle East countries that used both PAL and SECAM broadcasts).

Regarding early (analog) videodiscs, the established Laserdisc standard supported only NTSC and PAL. However, a different optical disc format, the Thomson transmissive optical disc made a brief appearance on the market. At some point, it used a modified SECAM signal (single FM subcarrier at 3.6 MHz). The media’s flexible and transmissive material allowed for direct access to both sides without flipping the disc, a concept that reappeared in multi-layered DVDs about fifteen years later.

PAL signal details

For PAL-B/G the signal has these characteristics.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Bandwidth | 5 MHz |

| Horizontal sync polarity | Negative |

| Total time for each line | 64.000 μs |

| Front porch (A) | 1.65+0.4 −0.1 μs |

| Sync pulse length (B) | 4.7±0.20 μs |

| Back porch (C) | 5.7±0.20 μs |

| Active video (D) | 51.95+0.4 −0.1 μs |

(Total horizontal sync time 12.05 µs)

After 0.9 µs a 2.25±0.23 μs colorburst of 10±1 cycles is sent. Most rise/fall times are in 250±50 ns range. Amplitude is 100% for white level, 30% for black, and 0% for sync. The CVBS electrical amplitude is Vpp 1.0 V and impedance of 75 Ω.

The vertical timings are:

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Vertical lines | 312.5 (625 total) |

| Vertical lines visible | 288 (576 total) |

| Vertical sync polarity | Negative (burst) |

| Vertical frequency | 50 Hz |

| Sync pulse length (F) | 0.576 ms (burst) |

| Active video (H) | 18.4 ms |

(Total vertical sync time 1.6 ms)

As PAL is interlaced, every two fields are summed to make a complete picture frame.

Luminance, Y, is derived from red, green, and blue (R’G’B’) signals:

U and V are used to transmit chrominance. Each has a typical bandwidth of 1.3 MHz.

Composite PAL signal

Subcarrier frequency

PAL broadcast systems

This table illustrates the differences:

| PAL B | PAL G, H | PAL I | PAL D/K | PAL M | PAL N | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transmission band | VHF | UHF | UHF/VHF* | VHF/UHF | VHF/UHF | VHF/UHF |

| Fields | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 60 | 50 |

| Lines | 625 | 625 | 625 | 625 | 525 | 625 |

| Active lines | 576 | 576 | 576 | 576 | 480 | 576 |

| Channel bandwidth | 7 MHz | 8 MHz | 8 MHz | 8 MHz | 6 MHz | 6 MHz |

| Video bandwidth | 5.0 MHz | 5.0 MHz | 5.5 MHz | 6.0 MHz | 4.2 MHz | 4.2 MHz |

| Colour subcarrier | 4.43361875 MHz | 4.43361875 MHz | 4.43361875 MHz | 4.43361875 MHz | 3.575611 MHz | 3.58205625 MHz |

| Vision/Sound carrier spacing | 5.5 MHz | 5.5 MHz | 6.0 MHz | 6.5 MHz | 4.5 MHz | 4.5 MHz |

* System I has never been used on VHF in the UK.

PAL-B/G/D/K/I

Many countries have turned off analog transmissions, so the following does not apply, except for using devices which output broadcast signals, such as video recorders. The resolution that PAL gave may or may not still be used, but HD or full HD are most commonly used in digital transmissions.

The majority of countries using PAL have television standards with 625 lines and 50 fields per second, differences concern the audio carrier frequency and channel bandwidths. The variants are:

Standards B/G are used in most of Western Europe, Australia, and New Zealand

Standard I in the UK, Ireland, Hong Kong, South Africa, and Macau

Standards D/K (along with SECAM) in most of Central and Eastern Europe

Standard D in mainland China. Most analogue CCTV cameras are Standard D.

Systems B and G are similar. System B is used for 7 MHz-wide channels on VHF, while System G is used for 8 MHz-wide channels on UHF (Australia uses System B on UHF). Similarly, Systems D and K are similar except for the bands they use: System D is only used on VHF (except in mainland China), while System K is only used on UHF. Although System I is used on both bands, it has only been used on UHF in the United Kingdom.

PAL-M (Brazil)

In Brazil, PAL is used in conjunction with the 525 line, 59.94 field/s system M, using (very nearly) the NTSC colour subcarrier frequency. Exact colour subcarrier frequency of PAL-M is 3.575611 MHz. Almost all other countries using system M use NTSC.

The PAL colour system (either baseband or with any RF system, with the normal 4.43 MHz subcarrier unlike PAL-M) can also be applied to an NTSC-like 525-line (480i) picture to form what is often known as “PAL-60” (sometimes “PAL-60/525”, “Quasi-PAL” or “Pseudo PAL”). PAL-M (a broadcast standard) however should not be confused with “PAL-60” (a video playback system—see below).

PAL-N (Argentina, Paraguay and Uruguay)

In Argentina, Paraguay and Uruguay the PAL-N variant is used. It employs the 625 line/50 field per second waveform of PAL-B/G, D/K, H, and I, but on a 6 MHz channel with a chrominance subcarrier frequency of 3.582056 MHz very similar to NTSC.

VHS tapes recorded from a PAL-N or a PAL-B/G, D/K, H, or I broadcast are indistinguishable because the downconverted subcarrier on the tape is the same. A VHS recorded off TV (or released) in Europe will play in colour on any PAL-N VCR and PAL-N TV in Argentina, Paraguay and Uruguay. Likewise, any tape recorded in Argentina, Paraguay or Uruguay off a PAL-N TV broadcast can be sent to anyone in European countries that use PAL (and Australia/New Zealand, etc.) and it will display in colour. This will also play back successfully in Russia and other SECAM countries, as the USSR mandated PAL compatibility in 1985—this has proved to be very convenient for video collectors.

People in Argentina, Paraguay and Uruguay usually own TV sets that also display NTSC-M, in addition to PAL-N. Direct TV also conveniently broadcasts in NTSC-M for North, Central, and South America. Most DVD players sold in Argentina, Paraguay and Uruguay also play PAL discs—however, this is usually output in the European variant (colour subcarrier frequency 4.433618 MHz), so people who own a TV set which only works in PAL-N (plus NTSC-M in most cases) will have to watch those PAL DVD imports in black and white (unless the TV supports RGB SCART) as the colour subcarrier frequency in the TV set is the PAL-N variation, 3.582056 MHz.

In the case that a VHS or DVD player works in PAL (and not in PAL-N) and the TV set works in PAL-N (and not in PAL), there are two options:

images can be seen in black and white, or

an inexpensive transcoder (PAL -> PAL-N) can be purchased in order to see the colours

Some DVD players (usually lesser known brands) include an internal transcoder and the signal can be output in NTSC-M, with some video quality loss due to the system’s conversion from a 625/50 PAL DVD to the NTSC-M 525/60 output format. A few DVD players sold in Argentina, Paraguay and Uruguay also allow a signal output of NTSC-M, PAL, or PAL-N. In that case, a PAL disc (imported from Europe) can be played back on a PAL-N TV because there are no field/line conversions, quality is generally excellent.

Extended features of the PAL specification, such as Teletext, are implemented quite differently in PAL-N. PAL-N supports a modified 608 closed captioning format that is designed to ease compatibility with NTSC originated content carried on line 18, and a modified teletext format that can occupy several lines.

Some special VHS video recorders are available which can allow viewers the flexibility of enjoying PAL-N recordings using a standard PAL ( 625/50 Hz ) colour TV, or even through multi-system TV sets. Video recorders like Panasonic NV-W1E (AG-W1 for the US), AG-W2, AG-W3, NV-J700AM, Aiwa HV-M110S, HV-M1U, Samsung SV-4000W and SV-7000W feature a digital TV system conversion circuitry.

Source From Wikipedia