This vast model reconstructing the city of Rome in the age of Constantine, created by the architect Italo Gismondi, is positioned in a center of a spacious Rome, at a low level to allow an easy view from above.

The reconstruction, at a scale of 1: 250, integrates the information from the marble Forma Urbis (the large plan of Rome created in the early III century AD) with data from the archaeological remains and ancient sources.

Ancient Rome

Life in ancient Rome revolved around the city of Rome, its famed seven hills, and its monumental architecture such as the Colosseum, Trajan’s Forum, and the Pantheon. The city also had several theaters, gymnasia, and many taverns, baths, and brothels. Throughout the territory under ancient Rome’s control, residential architecture ranged from very modest houses to country villas, and in the capital city of Rome, there were imperial residences on the elegant Palatine Hill, from which the word palace is derived. The vast majority of the population lived in the city center, packed into insulae (apartment blocks).

The city of Rome was the largest megalopolis of that time, with a population that may well have exceeded one million people, with a high-end estimate of 3.6 million and a low-end estimate of 450,000. A substantial proportion of the population under the city’s jurisdiction lived in innumerable urban centers, with population of at least 10,000 and several military settlements, a very high rate of urbanization by pre-industrial standards. The most urbanized part of the Empire was Italy, which had an estimated rate of urbanization of 32%, the same rate of urbanization of England in 1800. Most Roman towns and cities had a forum, temples and the same type of buildings, on a smaller scale, as found in Rome. The large urban population required an endless supply of food which was a complex logistical task, including acquiring, transporting, storing and distribution of food for Rome and other urban centers. Italian farms supplied vegetables and fruits, but fish and meat were luxuries. Aqueducts were built to bring water to urban centers and wine and oil were imported from Hispania, Gaul and Africa.

There was a very large amount of commerce between the provinces of the Roman Empire, since its transportation technology was very efficient. The average costs of transport and the technology were comparable with 18th-century Europe. The later city of Rome did not fill the space within its ancient Aurelian walls until after 1870.

The majority of the population under the jurisdiction of ancient Rome lived in the countryside in settlements with less than 10 thousand inhabitants. Landlords generally resided in cities and their estates were left in the care of farm managers. The plight of rural slaves was generally worse than their counterparts working in urban aristocratic households. To stimulate a higher labor productivity most landlords freed a large number of slaves and many received wages; but in some rural areas, poverty and overcrowding were extreme. Rural poverty stimulated the migration of population to urban centers until the early 2nd century when the urban population stopped growing and started to decline.

Starting in the middle of the 2nd century BC, private Greek culture was increasingly in ascendancy, in spite of tirades against the “softening” effects of Hellenized culture from the conservative moralists. By the time of Augustus, cultured Greek household slaves taught the Roman young (sometimes even the girls); chefs, decorators, secretaries, doctors, and hairdressers all came from the Greek East. Greek sculptures adorned Hellenistic landscape gardening on the Palatine or in the villas, or were imitated in Roman sculpture yards by Greek slaves. The Roman cuisine preserved in the cookery books ascribed to Apicius is essentially Greek.

Against this human background, both the urban and rural setting, one of history’s most influential civilizations took shape, leaving behind a cultural legacy that survives in part today.

The Roman Empire, at its height (c. 117 CE), was the most extensive political and social structure in western civilization. By 285 CE the empire had grown too vast to be ruled from the central government at Rome and so was divided by Emperor Diocletian into a Western and an Eastern Empire. The Roman Empire began when Augustus Caesar became the first emperor of Rome (31 BCE) and ended, in the west, when the last Roman emperor, Romulus Augustulus, was deposed by the Germanic King Odoacer (476 CE). In the east, it continued as the Byzantine Empire until the death of Constantine XI and the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1453 CE. The influence of the Roman Empire on western civilization was profound in its lasting contributions to virtually every aspect of western culture.

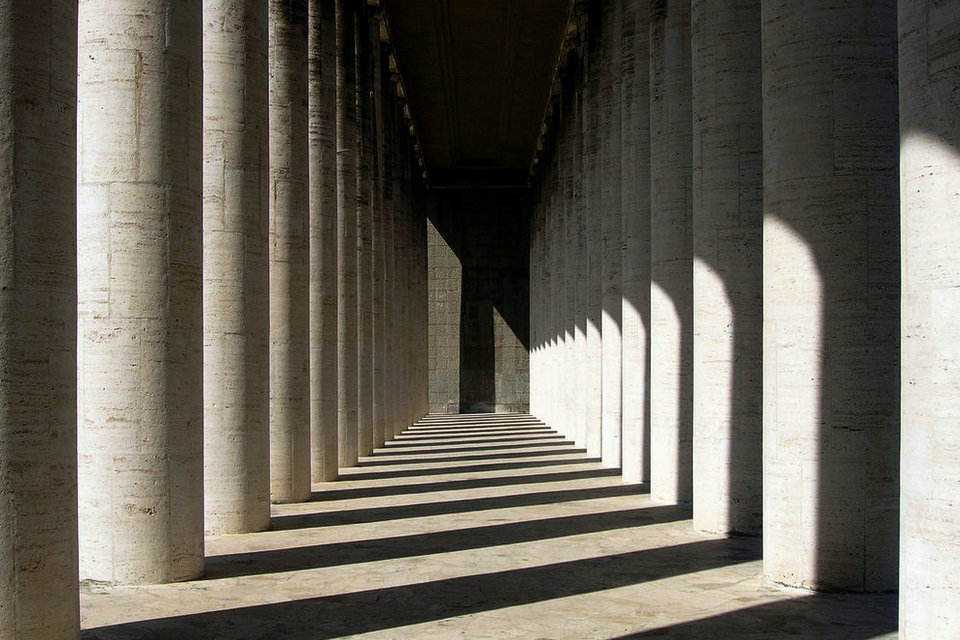

Architecture

In its initial stages, the ancient Roman architecture reflected elements of architectural styles of the Etruscans and the Greeks. Over a period of time, the style was modified in tune with their urban requirements, and civil engineering and building construction technology became developed and refined. The Roman concrete has remained a riddle, and even after more than two thousand years some ancient Roman structures still stand magnificently, like the Pantheon (with one of the largest single span domes in the world) located in the business district of today’s Rome.

The architectural style of the capital city of ancient Rome was emulated by other urban centers under Roman control and influence, like the Verona Arena, Verona, Italy; Arch of Hadrian, Athens, Greece; Temple of Hadrian, Ephesus, Turkey; a Theatre at Orange, France; and at several other locations, for example, Lepcis Magna, located in Libya. Roman cities were well planned, efficiently managed and neatly maintained. Palaces, private dwellings and villas, were elaborately designed and town planning was comprehensive with provisions for different activities by the urban resident population, and for countless migratory population of travelers, traders and visitors passing through their cities. Marcus Vitruvius Pollio, a 1st-century BCE Roman architect’s treatise “De architectura,” with various sections, dealing with urban planning, building materials, temple construction, public and private buildings, and hydraulics, remained a classic text until the Renaissance.

The chief Roman contributions to architecture were the arch, vault and the dome. Even after more than 2,000 years some Roman structures still stand, due in part to sophisticated methods of making cements and concrete. Roman roads are considered the most advanced roads built until the early 19th century. The system of roadways facilitated military policing, communications, and trade. The roads were resistant to floods and other environmental hazards. Even after the collapse of the central government, some roads remained usable for more than a thousand years.

Roman bridges were among the first large and lasting bridges, built from stone with the arch as the basic structure. Most utilized concrete as well. The largest Roman bridge was Trajan’s bridge over the lower Danube, constructed by Apollodorus of Damascus, which remained for over a millennium the longest bridge to have been built both in terms of overall span and length.

The Romans built many dams and reservoirs for water collection, such as the Subiaco Dams, two of which fed the Anio Novus, one of the largest aqueducts of Rome. They built 72 dams just on the Iberian peninsula, and many more are known across the Empire, some still in use. Several earthen dams are known from Roman Britain, including a well-preserved example from Longovicium (Lanchester).

The Romans constructed numerous aqueducts. A surviving treatise by Frontinus, who served as curator aquarum (water commissioner) under Nerva, reflects the administrative importance placed on ensuring the water supply. Masonry channels carried water from distant springs and reservoirs along a precise gradient, using gravity alone. After the water passed through the aqueduct, it was collected in tanks and fed through pipes to public fountains, baths, toilets, or industrial sites. The main aqueducts in the city of Rome were the Aqua Claudia and the Aqua Marcia. The complex system built to supply Constantinople had its most distant supply drawn from over 120 km away along a sinuous route of more than 336 km. Roman aqueducts were built to remarkably fine tolerance, and to a technological standard that was not to be equalled until modern times. The Romans also made use of aqueducts in their extensive mining operations across the empire, at sites such as Las Medulas and Dolaucothi in South Wales.

Insulated glazing (or “double glazing”) was used in the construction of public baths. Elite housing in cooler climates might have hypocausts, a form of central heating. The Romans were the first culture to assemble all essential components of the much later steam engine, when Hero built the aeolipile. With the crank and connecting rod system, all elements for constructing a steam engine (invented in 1712)—Hero’s aeolipile (generating steam power), the cylinder and piston (in metal force pumps), non-return valves (in water pumps), gearing (in water mills and clocks)—were known in Roman times.

Culture

In the ancient world, a city was viewed as a place that fostered civilization by being “properly designed, ordered, and adorned.” Augustus undertook a vast building programme in Rome, supported public displays of art that expressed the new imperial ideology, and reorganized the city into neighbourhoods (vici) administered at the local level with police and firefighting services. A focus of Augustan monumental architecture was the Campus Martius, an open area outside the city centre that in early times had been devoted to equestrian sports and physical training for youth. The Altar of Augustan Peace (Ara Pacis Augustae) was located there, as was an obelisk imported from Egypt that formed the pointer (gnomon) of a horologium. With its public gardens, the Campus became one of the most attractive places in the city to visit.

City planning and urban lifestyles had been influenced by the Greeks from an early period, and in the eastern Empire, Roman rule accelerated and shaped the local development of cities that already had a strong Hellenistic character. Cities such as Athens, Aphrodisias, Ephesus and Gerasa altered some aspects of city planning and architecture to conform to imperial ideals, while also expressing their individual identity and regional preeminence. In the areas of the western Empire inhabited by Celtic-speaking peoples, Rome encouraged the development of urban centres with stone temples, forums, monumental fountains, and amphitheatres, often on or near the sites of the preexisting walled settlements known as oppida. Urbanization in Roman Africa expanded on Greek and Punic cities along the coast.

The network of cities throughout the Empire (coloniae, municipia, civitates or in Greek terms poleis) was a primary cohesive force during the Pax Romana. Romans of the 1st and 2nd centuries AD were encouraged by imperial propaganda to “inculcate the habits of peacetime”. As the classicist Clifford Ando has noted:

Most of the cultural appurtenances popularly associated with imperial culture—public cult and its games and civic banquets, competitions for artists, speakers, and athletes, as well as the funding of the great majority of public buildings and public display of art—were financed by private individuals, whose expenditures in this regard helped to justify their economic power and legal and provincial privileges.

Even the Christian polemicist Tertullian declared that the world of the late 2nd century was more orderly and well-cultivated than in earlier times: “Everywhere there are houses, everywhere people, everywhere the res publica, the commonwealth, everywhere life.” The decline of cities and civic life in the 4th century, when the wealthy classes were unable or disinclined to support public works, was one sign of the Empire’s imminent dissolution.

In the city of Rome, most people lived in multistory apartment buildings (insulae) that were often squalid firetraps. Public facilities—such as baths (thermae), toilets that were flushed with running water (latrinae), conveniently located basins or elaborate fountains (nymphea) delivering fresh water, and large-scale entertainments such as chariot races and gladiator combat—were aimed primarily at the common people who lived in the insulae. Similar facilities were constructed in cities throughout the Empire, and some of the best-preserved Roman structures are in Spain, southern France, and northern Africa.

The public baths served hygienic, social and cultural functions. Bathing was the focus of daily socializing in the late afternoon before dinner. Roman baths were distinguished by a series of rooms that offered communal bathing in three temperatures, with varying amenities that might include an exercise and weight-training room, sauna, exfoliation spa (where oils were massaged into the skin and scraped from the body with a strigil), ball court, or outdoor swimming pool. Baths had hypocaust heating: the floors were suspended over hot-air channels that circulated warmth. Mixed nude bathing was not unusual in the early Empire, though some baths may have offered separate facilities or hours for men and women. Public baths were a part of urban culture throughout the provinces, but in the late 4th century, individual tubs began to replace communal bathing. Christians were advised to go to the baths for health and cleanliness, not pleasure, but to avoid the games (ludi), which were part of religious festivals they considered “pagan”. Tertullian says that otherwise Christians not only availed themselves of the baths, but participated fully in commerce and society.

Rich families from Rome usually had two or more houses, a townhouse (domus, plural domūs) and at least one luxury home (villa) outside the city. The domus was a privately owned single-family house, and might be furnished with a private bath (balneum), but it was not a place to retreat from public life. Although some neighbourhoods of Rome show a higher concentration of well-to-do houses, the rich did not live in segregated enclaves. Their houses were meant to be visible and accessible. The atrium served as a reception hall in which the paterfamilias (head of household) met with clients every morning, from wealthy friends to poorer dependents who received charity. It was also a centre of family religious rites, containing a shrine and the images of family ancestors. The houses were located on busy public roads, and ground-level spaces facing the street were often rented out as shops (tabernae). In addition to a kitchen garden—windowboxes might substitute in the insulae—townhouses typically enclosed a peristyle garden that brought a tract of nature, made orderly, within walls.

The villa by contrast was an escape from the bustle of the city, and in literature represents a lifestyle that balances the civilized pursuit of intellectual and artistic interests (otium) with an appreciation of nature and the agricultural cycle. Ideally a villa commanded a view or vista, carefully framed by the architectural design. It might be located on a working estate, or in a “resort town” situated on the seacoast, such as Pompeii and Herculaneum.

The programme of urban renewal under Augustus, and the growth of Rome’s population to as many as 1 million people, was accompanied by a nostalgia for rural life expressed in the arts. Poetry praised the idealized lives of farmers and shepherds. The interiors of houses were often decorated with painted gardens, fountains, landscapes, vegetative ornament, and animals, especially birds and marine life, rendered accurately enough that modern scholars can sometimes identify them by species. The Augustan poet Horace gently satirized the dichotomy of urban and rural values in his fable of the city mouse and the country mouse, which has often been retold as a children’s story.

On a more practical level, the central government took an active interest in supporting agriculture. Producing food was the top priority of land use. Larger farms (latifundia) achieved an economy of scale that sustained urban life and its more specialized division of labour. Small farmers benefited from the development of local markets in towns and trade centres. Agricultural techniques such as crop rotation and selective breeding were disseminated throughout the Empire, and new crops were introduced from one province to another, such as peas and cabbage to Britain.

Maintaining an affordable food supply to the city of Rome had become a major political issue in the late Republic, when the state began to provide a grain dole (Cura Annonae) to citizens who registered for it. About 200,000–250,000 adult males in Rome received the dole, amounting to about 33 kg. per month, for a per annum total of about 100,000 tons of wheat primarily from Sicily, north Africa, and Egypt. The dole cost at least 15% of state revenues, but improved living conditions and family life among the lower classes, and subsidized the rich by allowing workers to spend more of their earnings on the wine and olive oil produced on the estates of the landowning class.

The grain dole also had symbolic value: it affirmed both the emperor’s position as universal benefactor, and the right of all citizens to share in “the fruits of conquest”. The annona, public facilities, and spectacular entertainments mitigated the otherwise dreary living conditions of lower-class Romans, and kept social unrest in check. The satirist Juvenal, however, saw “bread and circuses” (panem et circenses) as emblematic of the loss of republican political liberty:

The public has long since cast off its cares: the people that once bestowed commands, consulships, legions and all else, now meddles no more and longs eagerly for just two things: bread and circuses.

Museum of Roman Civilization

The Museum of Roman Culture unites in its halls and extraordinary and rich display of various aspects of ancient Rome, documented in their entirety, through the combination of casts, models and reconstructions of works conserved in museums throughout the world and of monuments from all over the Roman Empire.

The Museum of Roman Civilization is located in Rome, in the EUR district. It documents the various aspects of Roman civilization, including habits and customs, through a very rich collection of copies of statues, casts of bas – reliefs, architectural models of individual works and monumental complexes, including large plastic models; all artifacts are made with an accuracy that makes them real works of art. Among the works on display, two stand out: the complete series of the casts of the Trajan ‘s Column and the large model of imperial Rome, made by Italo Gismondi. It is part of the “Shared museums” system of the municipality of Rome.

The course is divided into two sectors, one chronological and one thematic. The first, which is divided into twelve rooms, offers a historical summary of Rome from its origins to the 6th century AD; the thematic sector runs along twelve other rooms and documents the various aspects of daily life and material culture. The series of casts of the Trajan ‘s Column is exhibited within the thematic sector and at the end of it there is the large model of imperial Rome.

The visit to the museum is complementary to the observation of the ancient monuments of the capital, given that thanks to the very accurate models on display, the visitor can better understand their structure and original appearance. In addition, the museum excellently completes the visit to the city also because it allows you to get to know the most important works of the lands in which Roman civilization has spread and to know its many aspects of daily life. For these reasons, despite the almost total absence of original finds, the museum has a great didactic and documentary value.