History painting

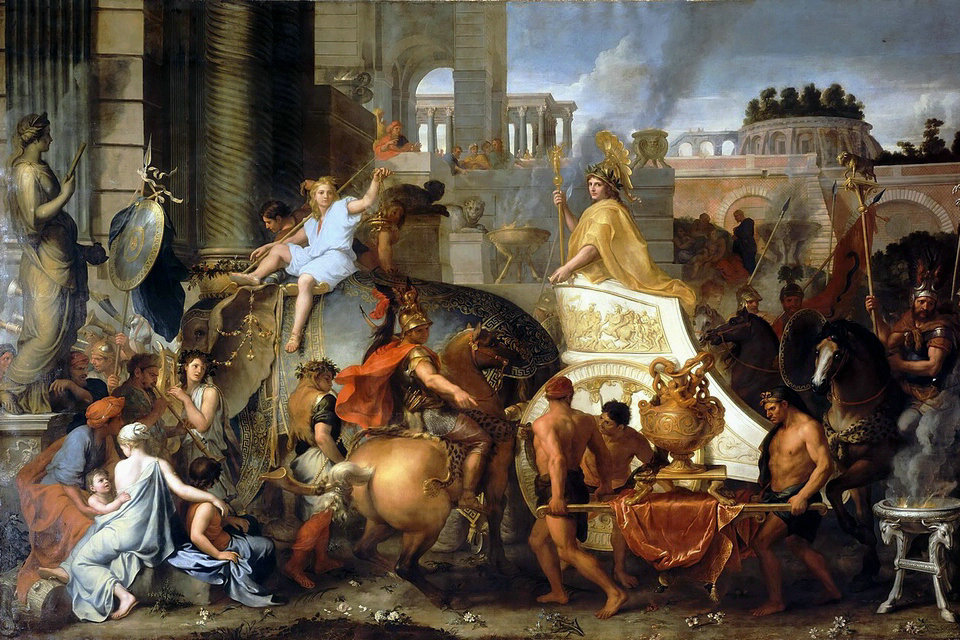

The history painting is an art form that its origins in the Renaissance has. In historical painting , historical, religious, mythical, legendary or literary material is shown condensed to an ahistorical moment . History painting is a genre in painting defined by its subject matter rather than artistic style. History paintings usually depict a moment in a narrative story, rather than a specific and static subject, as in a portrait.

The term is derived from the wider senses of the word historia in Latin and Italian, meaning “story” or “narrative”, and essentially means “story painting”. Most history paintings are not of scenes from history, especially paintings from before about 1850. An important characteristic of history painting is that the main characters shown are namable. [2] There is often the focus of a hero , a single personality shown as an autonomously acting. Historical images serve to deliberately transfigure them, to exaggerate them and to create a myth of history , not a realistic representation of past events. They were often commissioned, purchased or issued by rulers.

In modern English, historical painting is sometimes used to describe the painting of scenes from history in its narrower sense, especially for 19th-century art, excluding religious, mythological and allegorical subjects, which are included in the broader term history painting, and before the 19th century were the most common subjects for history paintings.

History paintings almost always contain a number of figures, often a large number, and normally show some type of action that is a moment in a narrative. The genre includes depictions of moments in religious narratives, above all the Life of Christ, as well as narrative scenes from mythology, and also allegorical scenes. These groups were for long the most frequently painted; works such as Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling are therefore history paintings, as are most very large paintings before the 19th century. The term covers large paintings in oil on canvas or fresco produced between the Renaissance and the late 19th century, after which the term is generally not used even for the many works that still meet the basic definition.

History painting may be used interchangeably with historical painting, and was especially so used before the 20th century. Where a distinction is made, “historical painting” is the painting of scenes from secular history, whether specific episodes or generalized scenes. In the 19th century, historical painting in this sense became a distinct genre. In phrases such as “historical painting materials”, “historical” means in use before about 1900, or some earlier date.

Assessment

History painting was traditionally considered the most important genre. This preeminence is explained within a certain concept of art in general: it is not valued so much that art imitates life, but rather that it proposes noble and plausible examples. It is not narrated what men do but what they can do. That is why the superiority of those artistic works in which what is narrated is considered high or noble is defended.

The Renaissance artist Alberti, in his work De Pictura, Book II, pointed out that “the relevance of a painting is not measured by its size, but by what it tells, by its history.” 2 The idea comes from classical Greece, in which tragedy was valued more, that is, the representation of a noble action performed by gods or heroes, than comedy, which was understood as the everyday actions of vulgar people. In this sense, Aristotle, in his Poetics, ends up giving prevalence to poetic fiction, since it narrates what could happen, what is possible, plausible or necessary, rather than what actually happened, which would be the field of the historian. Now, bearing in mind that it is not that this fiction is pure invention or fantasy, but that the myth is fabulation, stylization or idealization based on historically possible human examples. When Aristotle values tragedy above all else, it is because, of all possible human actions, those he imitates are the best and the noblest.

That is why, when in 1667 André Félibien (historiographer, architect and theorist of French classicism) hierarchized the pictorial genres, he reserved the first place to history painting, which he considered the grand genre. During the 17th to 19th centuries, this genre was the touchstone of every painter, in which he had to strive to stand out, and which earned him recognition through prizes (such as the Rome Prize), the favor of the general public and even admission to academiesOf paint. In addition to the high level of the message they transmitted, there were technical reasons. Indeed, this type of painting required the artist to have a great command of other genres such as portraiture or landscape, and he had to have a certain culture, with particular knowledge of literature and history.

Certainly, this position began to decline from the end of the 18th century and throughout the 19th century, to the benefit of other genres such as portraiture, genre scenes and landscape. Little by little, the representation of what classical art considered “comedy” began to be more valued: the everyday, the minor stories of vulgar people. Not by chance, Hogarth’s representations of his contemporaries were called by this comic history painting ” comic history painting.”

Features

History painting is characterized, in terms of its content, as a narrative painting: the represented scene tells a story. Thus it expresses an interpretation of life or conveys a moral or intellectual message.

They are usually large format paintings, large dimensions. There is a concentration of a few main characters amidst other minor characters in a confused crowd. And all this framed, generally in the background and the least prominent places of the painting, in architectural structures typical of the time being represented.

Colors are usually sober. Care is given to accessories, details of clothing or objects related to the topic to be treated. However, the event, if appropriate, need not have occurred exactly as it is portrayed, and artists often take great liberties with historical events in portraying the desired message. This was not always the case, since at the beginning the artists dressed their characters in classic costumes, regardless of when the events reported had occurred. When Benjamin West set out to depict The Death of General Wolfe in 1770In contemporary dress, several people firmly told him to wear classic clothing. But he represented the scene in the clothes of the moment the event occurred. Although King George III refused to buy the work, West succeeded both in overcoming his critics’ objections and in inaugurating a more historically appropriate style in such paintings.

The genus history painting

One reason for the emergence of this art discipline was the changing awareness of history as well as an associated need to depict the past with certain intentions. Artists painted historical motifs in large format and sometimes in coherence with the exhibition location, which they interpreted and faked in pictures.

Common to historical painting in all art-historical epochs is the demarcation from the event picture, which often represented everyday events such as field work or city life. The historical picture, on the other hand, can and wants to tell of the historically special moment through timeless and transferable symbolism. The question often arises as to whether a historical picture is art or history. Both disciplines can give an answer to this, which must be understood depending on the scientific perspective.

For the historianthe historical picture is also history or history in so far as the abstracted historical moment is abstracted from the history of origin and the circumstances in which the painter found himself. Views and intentions as well as design means typical of a time give the historical picture an actual historical content. The content, which is often cleverly staged, manipulated or trimmed by a truth, is merely the interpretation of an event or the interpretation of the past by the artist. From this point of view, one can now approach the picture from the perspective of art. The content and expression of historical images are determined by the aesthetic design principles of art, so that the visual staging of history must be viewed as an art (work).

Even the artistic staging and design of the painter is usually not under his own direction, as intentions such as the adoration of the rulers, which were often commissioned by the depicted parties themselves to legitimize a person or a state and to legitimize it. In this way, artistic self-work and political interests are mutually exclusive. However, this dimension was not necessarily clear to the contemporary viewer, since the often transfigured representation had a real effect on the recipient. So there was rarely a separation of fiction and reality, which was due to the level of education but also the degree of maturity of large sections of society.

Furthermore, the tangibility of the medium image was an advantage, since something was apparently objectively depicted in it. In this sense, the artist interpreted the past in the present, the time the picture was created, taking a certain perspective, and thus updated it for the public. The viewer should be shown a symbiosis between the past and the future initiated by the image, with the aim of historicizing the material depicted in the memory. This visual offer was particularly attractive for naive and uneducated recipients.

Prestige

History paintings were traditionally regarded as the highest form of Western painting, occupying the most prestigious place in the hierarchy of genres, and considered the equivalent to the epic in literature. In his De Pictura of 1436, Leon Battista Alberti had argued that multi-figure history painting was the noblest form of art, as being the most difficult, which required mastery of all the others, because it was a visual form of history, and because it had the greatest potential to move the viewer. He placed emphasis on the ability to depict the interactions between the figures by gesture and expression.

This view remained general until the 19th century, when artistic movements began to struggle against the establishment institutions of academic art, which continued to adhere to it. At the same time, there was from the latter part of the 18th century an increased interest in depicting in the form of history painting moments of drama from recent or contemporary history, which had long largely been confined to battle-scenes and scenes of formal surrenders and the like. Scenes from ancient history had been popular in the early Renaissance, and once again became common in the Baroque and Rococo periods, and still more so with the rise of Neoclassicism. In some 19th or 20th century contexts, the term may refer specifically to paintings of scenes from secular history, rather than those from religious narratives, literature or mythology.

Development

The term is generally not used in art history in speaking of medieval painting, although the Western tradition was developing in large altarpieces, fresco cycles, and other works, as well as miniatures in illuminated manuscripts. It comes to the fore in Italian Renaissance painting, where a series of increasingly ambitious works were produced, many still religious, but several, especially in Florence, which did actually feature near-contemporary historical scenes such as the set of three huge canvases on The Battle of San Romano by Paolo Uccello, the abortive Battle of Cascina by Michelangelo and the Battle of Anghiari by Leonardo da Vinci, neither of which were completed. Scenes from ancient history and mythology were also popular. Writers such as Alberti and the following century Giorgio Vasari in his Lives of the Artists, followed public and artistic opinion in judging the best painters above all on their production of large works of history painting (though in fact the only modern (post-classical) work described in De Pictura is Giotto’s huge Navicella in mosaic). Artists continued for centuries to strive to make their reputation by producing such works, often neglecting genres to which their talents were better suited.

There was some objection to the term, as many writers preferred terms such as “poetic painting” (poesia), or wanted to make a distinction between the “true” istoria, covering history including biblical and religious scenes, and the fabula, covering pagan myth, allegory, and scenes from fiction, which could not be regarded as true. The large works of Raphael were long considered, with those of Michelangelo, as the finest models for the genre.

In the Raphael Rooms in the Vatican Palace, allegories and historical scenes are mixed together, and the Raphael Cartoons show scenes from the Gospels, all in the Grand Manner that from the High Renaissance became associated with, and often expected in, history painting. In the Late Renaissance and Baroque the painting of actual history tended to degenerate into panoramic battle-scenes with the victorious monarch or general perched on a horse accompanied with his retinue, or formal scenes of ceremonies, although some artists managed to make a masterpiece from such unpromising material, as Velázquez did with his The Surrender of Breda.

An influential formulation of the hierarchy of genres, confirming the history painting at the top, was made in 1667 by André Félibien, a historiographer, architect and theoretician of French classicism became the classic statement of the theory for the 18th century:

Celui qui fait parfaitement des païsages est au-dessus d’un autre qui ne fait que des fruits, des fleurs ou des coquilles. Celui qui peint des animaux vivants est plus estimable que ceux qui ne représentent que des choses mortes & sans mouvement; & comme la figure de l’homme est le plus parfait ouvrage de Dieu sur la Terre, il est certain aussi que celui qui se rend l’imitateur de Dieu en peignant des figures humaines, est beaucoup plus excellent que tous les autres… un Peintre qui ne fait que des portraits, n’a pas encore cette haute perfection de l’Art, & ne peut prétendre à l’honneur que reçoivent les plus sçavans. Il faut pour cela passer d’une seule figure à la représentation de plusieurs ensemble; il faut traiter l’histoire & la fable; il faut représenter de grandes actions comme les historiens, ou des sujets agréables comme les Poëtes; & montant encore plus haut, il faut par des compositions allégoriques, sçavoir couvrir sous le voile de la fable les vertus des grands hommes, & les mystères les plus relevez.

He who produces perfect landscapes is above another who only produces fruit, flowers or seashells. He who paints living animals is more than those who only represent dead things without movement, and as man is the most perfect work of God on the earth, it is also certain that he who becomes an imitator of God in representing human figures, is much more excellent than all the others… a painter who only does portraits still does not have the highest perfection of his art, and cannot expect the honour due to the most skilled. For that he must pass from representing a single figure to several together; history and myth must be depicted; great events must be represented as by historians, or like the poets, subjects that will please, and climbing still higher, he must have the skill to cover under the veil of myth the virtues of great men in allegories, and the mysteries they reveal”.

By the late 18th century, with both religious and mytholological painting in decline, there was an increased demand for paintings of scenes from history, including contemporary history. This was in part driven by the changing audience for ambitious paintings, which now increasingly made their reputation in public exhibitions rather than by impressing the owners of and visitors to palaces and public buildings. Classical history remained popular, but scenes from national histories were often the best-received. From 1760 onwards, the Society of Artists of Great Britain, the first body to organize regular exhibitions in London, awarded two generous prizes each year to paintings of subjects from British history.

The unheroic nature of modern dress was regarded as a serious difficulty. When, in 1770, Benjamin West proposed to paint The Death of General Wolfe in contemporary dress, he was firmly instructed to use classical costume by many people. He ignored these comments and showed the scene in modern dress. Although George III refused to purchase the work, West succeeded both in overcoming his critics’ objections and inaugurating a more historically accurate style in such paintings. Other artists depicted scenes, regardless of when they occurred, in classical dress and for a long time, especially during the French Revolution, history painting often focused on depictions of the heroic male nude.

The large production, using the finest French artists, of propaganda paintings glorifying the exploits of Napoleon, were matched by works, showing both victories and losses, from the anti-Napoleonic alliance by artists such as Goya and J.M.W. Turner. Théodore Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa (1818–1819) was a sensation, appearing to update the history painting for the 19th century, and showing anonymous figures famous only for being victims of what was then a famous and controversial disaster at sea. Conveniently their clothes had been worn away to classical-seeming rags by the point the painting depicts. At the same time the demand for traditional large religious history paintings very largely fell away.

In the mid-nineteenth century there arose a style known as historicism, which marked a formal imitation of historical styles and/or artists. Another development in the nineteenth century was the treatment of historical subjects, often on a large scale, with the values of genre painting, the depiction of scenes of everyday life, and anecdote. Grand depictions of events of great public importance were supplemented with scenes depicting more personal incidents in the lives of the great, or of scenes centred on unnamed figures involved in historical events, as in the Troubadour style. At the same time scenes of ordinary life with moral, political or satirical content became often the main vehicle for expressive interplay between figures in painting, whether given a modern or historical setting.

By the later 19th century, history painting was often explicitly rejected by avant-garde movements such as the Impressionists (except for Édouard Manet) and the Symbolists, and according to one recent writer “Modernism was to a considerable extent built upon the rejection of History Painting… All other genres are deemed capable of entering, in one form or another, the ‘pantheon’ of modernity considered, but History Painting is excluded”.

15th century

In addition to the disciplines of genre, portrait, landscape and still life, history painting also developed in the 15th century. Not least due to the increasing concern with one’s own identity and the past of society, this genre was formed through a previously unavailable awareness of history and the past.

There was a consensus that a person is more difficult to depict than a landscape and for this reason a hierarchization gradually developed among the painters. They enjoyed a higher reputation for the creation of histories or portraits and also better pay. The content and motifs of the first historical pictures were based on elements and figures from the ancient world and thus adapted the figures or themes of mythology. In addition to this creative function, the pictures all had historical or religious content, and not seldom did they combine both in the picture.

The center of the first phase of history painting is Italy, where Leon Battista Alberti dealt early with the art theory of this type of painting. For him, the history painter should have a special status among the other artists. In addition to historical factual knowledge, which was important for the content of the picture, the painter should be able to inspire the viewer with the way he designed the reality. In order to leave this effect on the recipient, the primary educational goal of a painter was the study of nature and mathematics – not humanistic education – in order to make figures and elements of the picture as appealing as possible through the mimesis of reality.

16th century

The design principles of the 15th century should initially be adhered to in the following 16th century. The view of the slowly constituting Italian art theory was still to provide the painter with guidelines and framework for his work. The fact that historical painters must also have knowledge of the historical material they portrayed further matured. The form of representation also had the claim that the viewer should be attracted to the image and affected. The demand for the preservation of convenevolezza was new- attention to the appropriateness of the presentation. In theory, idealizing motifs were pushed back as far as possible and appealed to the painter’s art of representation. In addition to the influences of the Catholic Church on motifs and picture content – in many cases works of art were interpreted as sermons in pictures – the demand for a simple reading of the pictures marked this phase of historical painting. Gabriele Paleotti called for a stringent and clear design, which should make it easier for the viewer to read the pictures. Furthermore, he saw in the medium image the opportunity to address a much larger group of recipients than was possible with writings and texts, since only a few people enjoyed training in reading and writing. The epoch transition from Renaissance toBaroque, who is known as Mannerism, portrayed the painter not only as an artisan who designed pictures, but rather as the creator of a work whose talent is reflected in the works he created.

17th century

Towards the end of the 16th century and at the beginning of the 17th century, the center of (historical) painting shifted increasingly from Italy to France. Here too, opinions about the purpose and content of historical painting increasingly split. On the one hand, this type of image became the subject of the discipline now institutionalized at the Académie Française. The Academy’s Art Committee had both organizational and conceptual tasks in the field of painting. The council decided on the status of the professional title of painter, on the rules of the prevailing art, on the apprenticeship and teaching of painters and the functionalization of painting in political matters. On the other hand, painters and critics like Roger de Piles stoppedthe independence of the painters. De Piles took a clear opposition to academic art, the core of which referred to the perception of the painter and not to established regularities. Both approaches to art theory, that of the academy and the de Piles, combined the educational and moral aspect of the historical images.

18th century

The preliminary work of the 17th century in the field of art criticism opened up an even greater discussion in the 18th century in institutions, but also by private individuals with the subject of historical painting. Denis Diderotre-exposed the conflict that already existed between the basic ideas of the Académie Française and those of de Piles. An opposition between aesthetic design principles in the sense of the painter himself and the conservative rules of painting is difficult to reconcile, says Diderot. In contemporary painters, he saw only the inability to transfer moral statements of the hero characters depicted, so that there was no expression of passion. Diderot’s thoughts on aesthetics even went beyond the old principles of the genre and he gave painters of expressive landscape paintings the same status as history painters.

The art theorist Louis Etienne Watelet, on the other hand, clearly rejected this assessment and considered the genre hierarchy in painting to be justified. Since the history painter needs more knowledge than artists from other disciplines, he must also receive more fame and support, Watelet said. He also demanded that the public and the institutions as well as rulers have to support the history painter with orders.

The discussion between the rules of painting and the independent design principles was decisively broken by the painter Benjamin West. West’s painting The Death of General Wolfe no longer focused directly on the design principle, but rather on the content depicted. West, as the title suggests, painted the death of British general James Wolfe in the battle at the Abraham levelagainst French troops near Quebec in September 1759. What was special about this picture was that it showed an event in contemporary history and was made immediately after the general’s death. After some discussions about the exhibition of the picture, West was able to prevail and it was made accessible to the public. West based his picture on the fact that, in addition to the position of the painter, he also saw himself as a historian, whose duty it was to document such an important contemporary history in the medium of the image.

Initially, “history painting” and “historical painting” were used interchangeably in English, as when Sir Joshua Reynolds in his fourth Discourse uses both indiscriminately to cover “history painting”, while saying “…it ought to be called poetical, as in reality it is”, reflecting the French term peinture historique, one equivalent of “history painting”. The terms began to separate in the 19th century, with “historical painting” becoming a sub-group of “history painting” restricted to subjects taken from history in its normal sense. In 1853 John Ruskin asked his audience: “What do you at present mean by historical painting? Now-a-days it means the endeavour, by the power of imagination, to portray some historical event of past days.” So for example Harold Wethey’s three-volume catalogue of the paintings of Titian (Phaidon, 1969–75) is divided between “Religious Paintings”, “Portraits”, and “Mythological and Historical Paintings”, though both volumes I and III cover what is included in the term “History Paintings”. This distinction is useful but is by no means generally observed, and the terms are still often used in a confusing manner.

Because of the potential for confusion modern academic writing tends to avoid the phrase “historical painting”, talking instead of “historical subject matter” in history painting, but where the phrase is still used in contemporary scholarship it will normally mean the painting of subjects from history, very often in the 19th century. “Historical painting” may also be used, especially in discussion of painting techniques in conservation studies, to mean “old”, as opposed to modern or recent painting.

19th century

History painting in the area of today’s Germany later developed as z. B. in Italy and France. Images from the late 18th and early 19th centuries showed epic-philosophically exaggerated events in world or regional history up to folk tales; military and battle paintings as well as monumental paintings predominated.

In the second half of the 19th century, some major European powers pushed ahead with their colonization efforts. This opened up new perspectives and content for painters. The cult of people was also practiced in the medium of the picture. Also patriotism was discussed figuratively.

With regard to the form of the representation, the art critic Robert Vischer demanded that historical pictures should be “cheerful and myth-empty” and should have a clear artistic color. Accordingly, like some of his European predecessors, he established rules of art, which he was later to revise in favor of the freedom of art. His ideal now was free artistic development, which, however, should aim for an expressive picture.

Cornelius Gurlitt transferred this conflict between historical knowledge and the design of the pictures, which Alberti discussed in the 15th century, to the recipients. In his view, viewing the historical pictures by an uneducated viewer means only half the aesthetic and factual enjoyment. Furthermore, he appealed to the design principles of contemporary painters, because they idealize the depiction of people and facts, and, as a result, they clarify history and evoke a “stunted reality”.

Richard Muther saw it similarly, although he analyzed it somewhat more distantly by attributing the task of historical painting to conveying historical knowledge. The function and purpose of historical painting was particularly complex in the 19th century, as a spectrum of the use of private edification and sentimental emotion, scientific knowledge and illustrative instruction can be recorded.

The year 1871 was particularly significant in Prussia. After Prussia’s victory against France in the Franco-Prussian War in 1870/71 and the proclamation of the German Reich in Versailles, i.e. on hostile territory, the past was received by numerous painters in favor of the political ruling elite, including the emperor, in order to legitimize the long-forced national unity. From the second half of the 19th century, five central motifs can be identified, which were to serve this purpose in a manipulative manner: The first of these motifs was the battle in the Teutoburg Forest in 9 AD between Varus and Arminius, also known as Hermann der Cherusker, from whom Hermann emerged as the winner, who was understood as the first German in the pictorial re-functionalization of the 19th century. As a result of the founding of the empire, he was not only paid homage to in some paintings, such as those of Karl Friedrich Schinkel and Friedrich Gunkel, but also the Hermann monument in Detmold, inaugurated in 1875.

The second historical event that was received and alienated in many ways is the death of Frederick I Barbarossa. His death in Anatolia during the Crusades in 1190 was adapted and functionalized by artists. So Wilhelm I appears in a picture in the Barbarossa scroll, which should not imitate the Holy Roman Emperor, but should rather be interpreted as a picture of the successor or executor of Frederick I’s intentions. Since Barbarossa had a strong resemblance to the crucified Jesus in contemporary painting, not only appealed to political traditions, but also to the religiosity of the nation. Friedrich Kaulbach tooand Hermann Wislicenus (Goslar Imperial Palace) worked on the Barbarossa motif and transfigured it in the sense of political intentions. The presence of the name Barbarossa was clearly felt even beyond the turn of the century, because not only Wilhelm I, but also Adolf Hitler with the Barbarossa company tried to legitimize their claims to power and rule in Europe with the name of the former emperor.

A person whose religious background was updated as a German in the 19th century is also used for the next motif. Martin Luther, who was portrayed in pictures by artists, although he lived much sooner, as an enlightener. In this example, too, the painter interprets a historical event in a retrospective: the burning of the threat of ban by Luther in 1520. Catel considers this in his picture Martin Luther burns the papal bull and canon law. Luther is represented in the design symbolism of the 19th century as the reformer and enlightener of the Germans, who brought the language of the many to the few (educated) through his Bible translations, at the same time suggesting to the viewer of these pictures that Luther was the founder of the Protestant Empire. The Reformation served as an important hub of the origin of national unity in the estrangement through the art and politics of the 19th century.

In the chronological order of time, the next historical event can only be located again at the beginning of the 19th century. The Battle of the Nations near Leipzig in 1813 and the preceding years of the war not only influenced political and literary writings, but also contemporary painting. The intellectual elite prepared themselves in words and pictures to achieve solidarity and patriotic cohesion among the population towards the French enemy led by Napoleon.

The painting Ferdinande von Schmettau sacrificing her hair on the altar of the fatherland was one of the best known pictures of the time; it combined all motifs in the picture and title intended for the historical event. The elements of unity and willingness to make sacrifices as well as religious motifs become clear in the title and in the graphic representation and are expanded by other works in areas such as voluntary declaration of war and later by the motive of the winner. Like the Barbarossa motif, that of the Battle of Nations near Leipzig influenced the history of the following century. In 1913 the Monument to the Battle of the Nationsinaugurated near Leipzig and alienation also took place here. The memorial, designed for the fallen, served as a symbol of the German victory, but without the Russian-Austrian alliance against Napoleon the latter would probably not have been defeated.

The fifth significant historical event is the foundation of the German Reich, the unification of Germany. At the historical moment of the Imperial Proclamation, German history seemed to have been fulfilled as a military victory for the German armies under the leadership of Prussia. Anton von Werner was commissioned to take part in this event as an artist in order to capture it in the picture. Werner’s three versions of his painting The Proclamation of the German Empire (January 18, 1871) show how history can be received and shaped by the painter. The perspective of the viewer changes in all pictures, so that the perspective of the German princes and the military in the version for theBerlin Castle from 1877, the Prussian army in the version for the Hall of Fame Berlin from 1882 and the Hohenzollern family as a gift to Bismarck from 1885 is represented. A side effect of the change in perspective is the increase in detail. The last, the Friedrichsruher version, focuses on Kaiser Wilhelm I and Crown Prince Friedrich III., Bismarck, Moltke and Roon. Werner painted them all in a photo-realistic manner as they look in the present, not in 1871 but in 1885. He showed how far they have come in the present. Only the long-deceased Roon, who was unable to attend the proclamation, was painted as he had looked in 1871 and remembered by the other portrayed, and how he had portrayed him in 1871. Werner’s goal in this version was to highlight the merits of the emperor and Bismarck as well as the Prussian generals in the fifteenth year of the empire. Here too, the history picture does not show what history was like, but should be seen.

Similar to Anton von Werner, Hermann Wislicenus was also commissioned to design paintings that should form a symbiosis between history and the present. After the Kaiserpfalz Goslar became in need of renovation at the end of the 19th century, Wislicenus won a competition to renovate and redesign the residence. The 52 murals he designed in the Kaisersaalformed a chronological sequence of German history with topics such as the medieval imperial glory, an Sleeping Beauty allegory, which stood for the awakening of the German states from deep political sleep, and ultimately the founding of the empire in 1871. The motifs symbolize the artist’s and the historical career of the empire, which has now been revived, for the clients.

What is important in all paintings of the time is that the viewer should be effective, which is why the appropriate way of publication had to be found to guarantee them. On the one hand, exhibitions such as the National Gallery (founded in 1861) were planned, which, based on the French model, were initially intended only for historical paintings. Another publication option was the use of the outside of public buildings, such as the Munich Hofarkaden. The histories created here were commissioned by the state and, in addition to the primary development of national pride, were also to be regarded as educational resources for the people. Peter von Corneliusgot to his proposal in 1826 through the award of the organization and design of arcades with 16 pictures of the history of the Wittelsbach house since the dynasty justification by Otto I.

Whether Ernst forester paintings liberation of the army in the bottleneck of Chiusa by Otto of Wittelsbach in 1155 or Karl Sturmer Max Emanuel conquering Belgrade in 1688, the respective important figures of the Wittelsbach house are always central as heroic figures in a glorious pose. This series of historical paintings also attempted to motivate people to patriotism in the country; although contemporary Sulzer notes that the pictures do have educational advantages in terms of content, but are no competition for historiography. As shown above, the reasons in the field of image design and motif selection are due to historically striking events and personalities. The viewer’s acceptance of these representations is based on the turning point in Europe after the phase of the French Revolution. The term freedom was henceforth tied to that of the nation or the state, and the community living in a state was thus oriented towards this. By visualizing myths and history, the concept of unity was interpreted as the primary goal on the way to the well-being of the nation. Mythical and legendary material, such as a sleeping Barbarossa, which portrays the political situation before the founding of the empire in 1871 as glaring in deep sleep, should enable historical references and continuity to previous epochs.

History painting and historical painting

The terms

Initially, “history painting” and “historical painting” were used interchangeably in English, as when Sir Joshua Reynolds in his fourth Discourse uses both indiscriminately to cover “history painting”, while saying “…it ought to be called poetical, as in reality it is”, reflecting the French term peinture historique, one equivalent of “history painting”. The terms began to separate in the 19th century, with “historical painting” becoming a sub-group of “history painting” restricted to subjects taken from history in its normal sense. In 1853 John Ruskin asked his audience: “What do you at present mean by historical painting? Now-a-days it means the endeavour, by the power of imagination, to portray some historical event of past days.” So for example Harold Wethey’s three-volume catalogue of the paintings of Titian (Phaidon, 1969–75) is divided between “Religious Paintings”, “Portraits”, and “Mythological and Historical Paintings”, though both volumes I and III cover what is included in the term “History Paintings”. This distinction is useful but is by no means generally observed, and the terms are still often used in a confusing manner. Because of the potential for confusion modern academic writing tends to avoid the phrase “historical painting”, talking instead of “historical subject matter” in history painting, but where the phrase is still used in contemporary scholarship it will normally mean the painting of subjects from history, very often in the 19th century. “Historical painting” may also be used, especially in discussion of painting techniques in conservation studies, to mean “old”, as opposed to modern or recent painting.

In 19th-century British writing on art the terms “subject painting” or “anecdotic” painting were often used for works in a line of development going back to William Hogarth of monoscenic depictions of crucial moments in an implied narrative with unidentified characters, such as William Holman Hunt’s 1853 painting The Awakening Conscience or Augustus Egg’s Past and Present, a set of three paintings, updating sets by Hogarth such as Marriage à-la-mode.

19th century

History painting was the dominant form of academic painting in the various national academies in the 18th century, and for most of the 19th, and increasingly historical subjects dominated. During the Revolutionary and Napoleonic periods the heroic treatment of contemporary history in a frankly propagandistic fashion by Antoine-Jean, Baron Gros, Jacques-Louis David, Carle Vernet and others was supported by the French state, but after the fall of Napoleon in 1815 the French governments were not regarded as suitable for heroic treatment and many artists retreated further into the past to find subjects, though in Britain depicting the victories of the Napoleonic Wars mostly occurred after they were over. Another path was to choose contemporary subjects that were oppositional to government either at home and abroad, and many of what were arguably the last great generation of history paintings were protests at contemporary episodes of repression or outrages at home or abroad: Goya’s The Third of May 1808 (1814), Théodore Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa (1818–19), Eugène Delacroix’s The Massacre at Chios (1824) and Liberty Leading the People (1830). These were heroic, but showed heroic suffering by ordinary civilians.

Romantic artists such as Géricault and Delacroix, and those from other movements such as the English Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood continued to regard history painting as the ideal for their most ambitious works. Others such as Jan Matejko in Poland, Vasily Surikov in Russia, José Moreno Carbonero in Spain and Paul Delaroche in France became specialized painters of large historical subjects. The style troubadour (“troubadour style”) was a somewhat derisive French term for earlier paintings of medieval and Renaissance scenes, which were often small and depicting moments of anecdote rather than drama; Ingres, Richard Parkes Bonington and Henri Fradelle painted such works. Sir Roy Strong calls this type of work the “Intimate Romantic”, and in French it was known as the “peinture de genre historique” or “peinture anecdotique” (“historical genre painting” or “anecdotal painting”).

Church commissions for large group scenes from the Bible had greatly reduced, and historical painting became very significant. Especially in the early 19th century, much historical painting depicted specific moments from historical literature, with the novels of Sir Walter Scott a particular favourite, in France and other European countries as much as Great Britain. By the middle of the century medieval scenes were expected to be very carefully researched, using the work of historians of costume, architecture and all elements of decor that were becoming available. And example of this is the extensive research of Byzantine architecture, clothing and decoration made in Parisian museums and libraries by Moreno Carbonero for his masterwork The Entry of Roger de Flor in Constantinople. The provision of examples and expertise for artists, as well as revivalist industrial designers, was one of the motivations for the establishment of museums like the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

New techniques of printmaking such as the chromolithograph made good quality monochrome print reproductions both relatively cheap and very widely accessible, and also hugely profitable for artist and publisher, as the sales were so large. Historical painting often had a close relationship with Nationalism, and painters like Matejko in Poland could play an important role in fixing the prevailing historical narrative of national history in the popular mind. In France, L’art Pompier (“Fireman art”) was a derisory term for official academic historical painting, and in a final phase, “History painting of a debased sort, scenes of brutality and terror, purporting to illustrate episodes from Roman and Moorish history, were Salon sensations. On the overcrowded walls of the exhibition galleries, the paintings that shouted loudest got the attention”. Orientalist painting was an alternative genre that offered similar exotic costumes and decor, and at least as much opportunity to depict sex and violence.