“An attempt to right – even slightly – the wrong that was being caused to the murdered people”

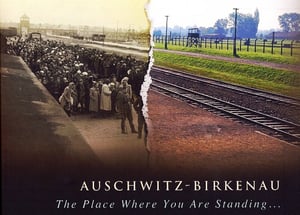

Nazi Germany occupied the region of Volhynia in North West Ukraine in June-July 1941. Only few of the Jews were able to escape from the rapidly advancing German army, and soon the mass shooting of Jews began by German killing units and Ukrainian auxiliary forces. The remaining Jews were confined in ghettos, where they were subjected to terrible conditions and forced labor. In summer 1942 a new wave of killings was launched. Until October of that year some 142,000 Jews in Volhynia had been murdered, and by the beginning of 1943 all remaining Jews in ghettos and camps where liquidated, and only a few managed to go into hiding with local Ukrainians or Poles or escape and join the partisans in Volhynia’s forests. It is estimated that only 1.5% of Volhynia’s Jews survived.

Many German agencies – SS, army, police and government offices and economic enterprises – participated in the destruction of the Jews. Many were ideologically motivated, others acquiesced, and only few had the courage to resist. One of the latter was a civilian engineer, Hermann Friedrich Graebe, who had been sent to Ukraine by the Josef Jung works in September 1941 to renovate the railroad system. Jung were employing a Jewish work force comprising some 5,000 men and women. While Jewish workers everywhere were exploited as slave laborers, Graebe became the protector and rescuer of his workers.

Born in 1900, in Gräfrath, a small town in the Rhineland in Germany, Graebe came from a poor family – his father was a weaver and his mother helped supplement the family’s income by working as a domestic. The Graebes were Protestants in a predominantly Roman Catholic area. Like many of his generation, Graebe had joined the Nazi party, but soon became disenchanted with the movement. After he had criticized the party, Graebe was apprehended by the Gestapo and jailed in for several months.

Graebe became witness to the atrocities perpetrated against the Jewish population. On October 5, 1942, he arrived at the mass-killing site near Dubno and saw how 5,000 Jewish men, women, and children, lined up naked in front of previously dug pits, were cold-bloodedly executed by SS firing squads and the Ukrainians.

“The people from the trucks – men, women and children – were forced to undress under the supervision of an SS soldier with a whip in his hand…. I watched a family of about eight…An old lady, her hair completely white, held the baby in her arms, rocking it, and singing it a song. The infant was crying aloud with delight. The parents watched the groups with tears in their eyes. The father held the ten-year-old boy by the hand, speaking softly to him: the child struggled to hold back his tears. Then the father pointed a finger to the sky, and, stroking the child’s head, seemed to be explaining something. At this moment, the SS near the ditch called something to his comrade. The latter counted off some twenty people and ordered them behind the mound. The family of which I have just spoken was in the group…. I walked around the mound and faced a frightful common grave. Tightly packed corpses were heaped so close together that only the heads showed.” Hermann Friedrich Graebe’s affidavit, Nuremberg, 10 November 1945

Propelled by moral indignation, Graebe set out to save as many Jews as he could. He deliberately accepted more assignments than his company could handle, and consequently requested to employ a greater number of Jewish workers. He established a branch in Poltava with the sole purpose of providing shelter to “his” Jews. His uneconomic practices began to arouse suspicion, but he somehow managed to avoid prosecution. In January 1944, when the Germans began retreating, he took his Jewish office team of twenty person with him and was able to protect them until the end of the war.

“Working in the technical department of the firm, I realized that it was receiving large orders. I feared that we would not be able to fulfill the orders, despite our long working hours. I turned to Graebe drew his attention to the large number of orders and even warned that he would not be able to meet the demand. After we had exchanged words he took me to his room and revealed his intention. The increase in orders would have to be matched with laborers. Since there were no Poles in the area, he would receive Jews who would be saved from being put in the ghetto or their deportation to Germany or to the camps.” From the testimony of Aloise Dudkovski, a Polish worker of Jung, 1965.

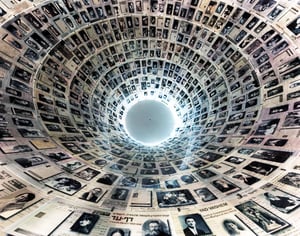

From February 1945 until the autumn of 1946, Graebe worked with the War Crimes Branch of the U.S. Army on the preparation of the Nuremberg trials, and became the only German who testified for the prosecution. In post-war German society he was regarded as a traitor and received some threats against his life. Consequently, in 1948 Graebe decided to emigrate to the United States and settle in San Francisco. Despite this forced exile, he considered himself to be a proud German, and continued his efforts to bring German war criminals to justice. His preoccupation with the Nazi past brought him some enemies in Germany who tried to besmirch his name. But the Jewish survivors remembered their rescuer. On March 23, 1965, Yad Vashem decided to recognize Hermann Friedrich Graebe as Righteous Among the Nations and he planted a tree in the Avenue of the Righteous on the Mount of Remembrance.

“He felt the eternal shame that the Nazis had brought onto the German people. And always said that his rescue operations were an attempt to right – even slightly – the wrong that was being caused to the murdered people and to the German people. He saved not only Jews, but also Poles. He was not a religious man, His motivation was humanitarian. What a great man!” From the testimony of Aloise Dudkovski, a Polish worker of Jung, 1965

“I have often been asked what brought me to help the Jews and to endanger my life and the lives of my family. The best explanation I can think of is that I remembered my mother who came from the family of petty farmers in Hessen, making their lives from an unfertile, poor soil. From my earliest youth my mother instilled one principle in me – not knowing that it came from the great philosopher and teacher Hillel, who lived in Jerusalem 2,000 years ago: ‘do not do to others that which you hate done unto yourself”. …To this day I have the deepest respect for my mother and I am grateful to her for having given me this to accompany me through life.” Hermann Friedrich Graebe, Yad Vashem, 1965.