Genealogy Tourism, sometimes called roots tourism, is a segment of the tourism market consisting of tourists who have ancestral connections to their holiday destination. These genealogy tourists travel to the land of their ancestors to reconnect with their past and “walk in the footsteps of their forefathers”.

Genealogy tourism is a worldwide industry, although it is more prominent in countries that have experienced mass emigration at some time in history and thus have a large worldwide Diaspora community.

Description

“Family history tourism is perfectly consistent with one of the most current trends in the market, that is, using the past as a resource. Today more and more this look back is left to an individual path, or to sites that work for those who want to put their past in order. And therefore your present “.

The bonds of kinship, affinity and relevance are the essential basis on which the genealogical research is based. Relevance is “the genealogical bond that exists between a person and another, who, although not a relative of his, is in any case genealogically related to the first, through a continuous series of bilateral relations of conjugal, daughter and brotherhood”; in common parlance, it is a logical or factual relationship, a relationship of affinity, function, friendship or interdependence.

The relationship of relevance must be understood in a broad sense: firstly, as a link between the tourist and other people who are not necessarily bound by relationships of kinship and affinity – we can also include the fellow soldiers, the associates, the confreres, among the relevant ones. and the university or college companions. Secondly, with things, territories, photographs, diaries, letters and memorials, with houses and ruins, and with the thousand roads of good or bad fate that marked the destinies of their ancestors.

Considering that genealogical and family history research, both strictly and broadly, is a basic aspect of genealogical tourism, archives play a considerable role.

Alex Haley, perhaps the first and also one of the most famous genealogical tourists, recounts, in his bestseller Radici, that he went innumerable times at the Library of Congress in Washington.

Museums are par excellence repositories of memories. Among those that we mention here: ethnographic, ecomuseums, some photographic collections, war and heraldic museums, some of the industrial museums, local history museums and surname museums. A surname can denote membership in a family, a parental bond, as well as the link with a nation, or more closely with a region, a community, a village: in the world meetings are held, even hundreds of people, planned for the more at yearly intervals, between carriers of the same surname, and not necessarily bound by blood ties.

Biographers, family historians, lovers of local history, archivists, cultural mediators and naturally genealogists constitute the human capital indispensable for the constitution of an offer adapted to the needs of demanding genealogical tourists.

Origin and developments

Genealogical tourism appeared at the same time as mass tourism, when the holidays became a consumer good for all walks of life. From the United States the African Americans began to want to discover their African origins, while the descendants of the European immigrants were able to afford return crossings and later the same implications were for the intra-European migrants.

The desire to rediscover one’s ancestors or one’s own ‘roots’ is a far-reaching phenomenon that invests the entire Western world and is related to the dissolution of generational cohesion and the loosening of those narratives capable of re-placing the individual within of a collective story. The rarefaction of history as a shared heritage leaves space for individual paths that seek to bring order into the past by reconnecting it to the present. The loss of continuity between ‘living and dead’ can be repaired by genealogical research, albeit only on an individual level. In a 1995 interview J. Revel, denounced the memorial obsession in progress in European society that manifested itself in an excess of museification and observed that: “our societies are thought as collections of individuals of which each would give a particular memory that would not be a summary or a bending of memory general but that would be valid for its own singularity “. It is an observation that gives meaning to the widespread ‘genealogical trend’ in progress.

It would seem that the search for places and the reconstructions of genealogical trees practiced in the archives compensate for a collective narration that failed. A society that perhaps no longer identifies itself only in the network of powers displaced on the territory by the central state and which instead seeks to support an alternative connective tissue. However, it is a positive phenomenon because it tends to rekindle the links between past and present taking the moves from the history of one’s family, which is then the fundamental constitutive core of every society. If this necessity is then carried out by employing do-it-yourself methodologies, often improvised, it is up to public institutions to grasp these signals and try to bring these new heritage of individual stories into the heritage of the community.

Genealogical culture belongs traditionally to the great families of feudal nobility. The Genealogy, throughout the ‘ modern age and until the’ nineteenth century, it is primarily rooted in the sphere of economic interests. Tests of ancestry and descent were often produced in hereditary processes for assets acquired, donated or come through through dowries, sealing the seal of agreements between powerful families or running for power. The successors rights were essentially based on parental hierarchies arranged in an extensive legal and custom system. Genealogists and distinguished lawyers were highly sought after for the dexterity with which they moved in the labyrinths of hereditary norms and customs.

The search for identity through the genealogical tree for bourgeois families, for the artisans and for the nuclei of small landowners, of workers and laborers, has developed in another context and only recently seems to have acquired its own sphere of diffusion. On the other hand, to social groups that have been perceived for centuries in a historical condition of mass, of movement or simply of distance from the top of the social pyramid, could not correspond to the genealogical representation just described.

The interest for the origins is in fact a phenomenon of the last thirty years that has been expressed in the search for the paths made by the members of a family rather than in the recognition of a patrimonial or blood bond with a legendary ancestor story here it does not mean conservation and duration but the transformation of large sectors of society, emancipation from conditions of poverty, overcoming the age-old lack of economic and intellectual means. History, then caesura, interruption, or even breaking of ties with the past and removal of younger generations from the older ones.

The advent of electronic communication and the diffusion of equipment and computer knowledge, facilitated also by the growing schooling, have influenced our imagination and the world in which we live.

In 1996 the magazine “Altreitalie” was also put online and was the first Italian scientific publication to be distributed in full and free on the internet. This specialized magazine on the subject of Italian migrations has helped to change the perception and knowledge of Italian migrants and has informed them about the history of their migrations and settlements. Until the year 2000 on the portal of the magazine were also available lists of Italian passengers disembarked, from 1859 to 1920, in the ports of New York, Buenos Aires and Vittoria.

Journeys back to the country of origin have always been a crucial moment for migrants and their children in the discovery and construction of their individual and family identity. For those who emigrated overseas in the twentieth century, and in particular for those who left after the Second World War, it was a well-established practice to make the first visit to the native places ten years after departure.

The second return trip normally took place after another ten years when the emigrant had created his family nucleus and felt the need to make their children know the country from which they came. The trip usually included a visit to major cities of art – Florence, Rome, Venice, etc. – and continued with the stay of a few weeks in the country of origin, thus giving the children the opportunity to meet the ‘root’ of the family that remained in Italy.

The return journey also represented a moment of redemption for the emigrant who could prove to himself and to those who had not emigrated both the success achieved and the validity of the choice to migrate.

Obviously the habits described differ according to the different migratory experiences because both the place and the historical period in which the departures took place are decisive. In any case, maintaining a link with Italy is much easier today than in the past. We live in a globalized world where the distances, thanks to the accessibility to low cost flights and the advent of the Internet, have become shorter.

Statistics

The archives are no longer the exclusive province of professional historians narrow elite of undergraduates and graduate students in history, aims to collect material for writing essays and dissertations. On the contrary, more and more in recent decades the public has expanded to various social classes each with their own memory needs and their identity needs.

The surveys show this: according to a survey carried out in the British archives in 2001, only 5.5% of users stated that the visit was for academic research purposes or similar, 9.6% was related to other professional and even 82.3% claimed to carry out research for personal interest or for hobbies.

Further research conducted the following year has investigated in detail the aims of these users and it has emerged that among them a good 71.8% carried out family history surveys. This is a fact that confirms a long-standing trend that began in the 1980s. In 1997 the Family Records Center was inaugurated in London, which saw its presence double in three years. To get an idea of the turnout in this center in 2002 there were about 300,000 visitors while in 2005, thanks to the networking of a large part of the archival heritage, they went down to 260,000.

In France between the seventies and the end of the nineties the number of users of the national and departmental archives has quadrupled, reaching 200,000 to be added another 100,000 amateur genealogists attending the halls of the various municipal archives. A survey carried out in 2003 confirmed that they were mostly non-professional users: 29% said they were attending national archives for academic and university study activities, another 29% in the context of a professional activity including research academic and 48% for personal reasons or for leisure. Percentage that rises to 56% among the general public of the municipal and departmental archives, reaching the latter up to 62%.

In the United States, a survey conducted in the year 2000 gave 60% of Americans likely to carry out genealogical research. Internet and computer science have revolutionized genealogy. In the US there are over two million websites published by “groups of friends” of the National Archives: genealogy is one of the most popular online hobbies. The US portal Ancestry.com that markets software to create genealogical trees and migration maps (graphically similar to family trees but family branches are linked by dates of family reunions and return visits) was born in 2004 and already the first year could boast 1,500,000 paying subscribers; Ancestry is a multinational company and in Italy markets its products through the www.ancestry.it website. The genealogists have exploited to their advantage the information revolution to reconstruct their family stories, to inquire about their origin logos and to book trips in order to reach them.

For Italy there are no precise statistics but the number of presences in the study rooms of the State Archives has risen from 78,000 in the decade 1963-72, to 127,000 in the following year, to about 200,000 in the decade 1983-92. In the last decade, 1995-2004, there were 313,000 visitors.

Dissemination: an overview

Depending on the place of departure and personal and family migration history we can distinguish between different types of genealogical tourist: the descendants of immigrants of European origin who return to their places of origin in Europe; the descendants of the first emigrants coming from Europe to emigration places of their ancestors in the new world and also those who follow the routes from the ports of embarkation to the ports of arrival – obviously in the case where entry and control points (like the hospedarias of Latin America) have been preserved and are proposed in tourist guides; the emigrants who return to visit the countries where they were born as tourists because they do not want or can not return permanently.

On the “active” front, that is the countries which, marked by the mass emigration of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, have put forward return tourism policies, Ireland was the first. In fact, Ireland and five other European countries – Germany, Poland, Greece, Scandinavia and the Netherlands – have been able to take advantage of European funds for the implementation of root tourism for the period 1993-1996. They launched a project called ‘Routes to the Roots’ whose common goal was to nurture and satisfy the strong identity demand formulated by their expatriate citizens. Even Lebanon, aware of the economic possibilities offered by its diasporic population, has devised a week-long tourist packages and has directed them to the young descendants of the Lebanese emigrants. The answer,

On the “passive” front, that is the countries that have welcomed the immigrants, the Americas are the most significant area of investigation both in numerical terms and because the genealogical trends in the USA (and in part also in Canada) are similar to those Australians and New Zealanders. These are the criteria that we will follow, in the following paragraphs, to develop our discourse on root tourism.

Americas

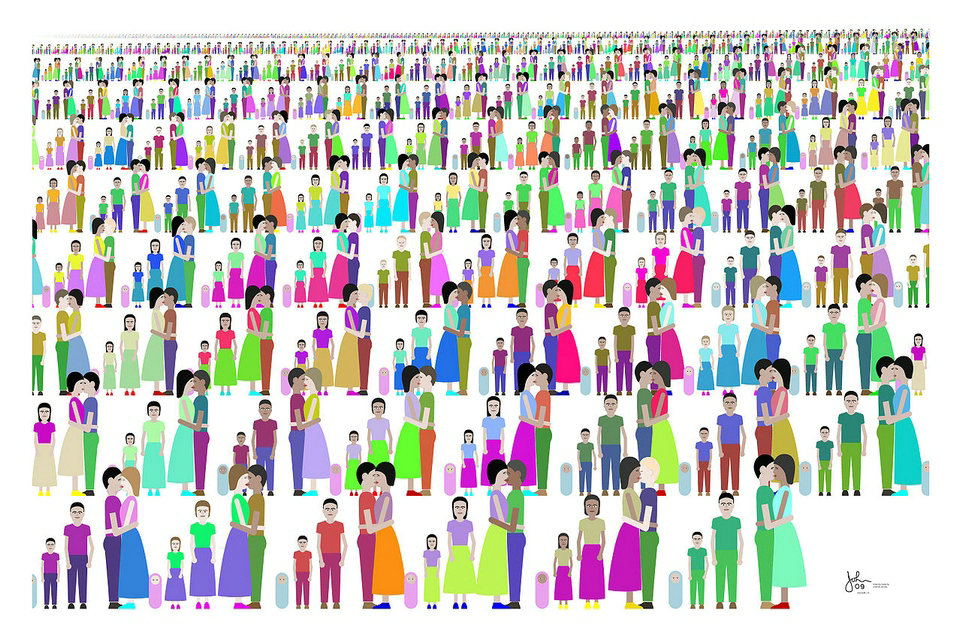

In 1815 there were 2000 passengers who emigrated from England to the United States. Their number rose progressively until reaching 57,000 in the 1830s. The famine of 1846-1847, however, brought in the United States two and a half million Irish. The failure of the revolts of 1848 also caused a mass emigration of the Germans: in 1847 they landed 100,000 and in 1854 had risen to double. The discovery of gold in California (1850), the colonization of the West and the early industrialization attracted about thirteen million foreigners between 1850 and 1890, of which almost 90% were Europeans. At the end of the nineteenth century the origin of the migrants changed: no longer from the northwestern countries but from Russia, Austria-Hungary and Italy. In addition to the USA, Canada was a privileged destination, while towards Latin America, Italians, French, Portuguese and Spanish were oriented above all1. If we add to these data the impressive ones of the Chinese diaspora and those of internal migrations, it is clear that the Americas constitute a potentially huge reservoir of genealogical tourists.

USA

The baby boomers represent a third of the American population and today make up about 80% of the entire population included in the age group between 50 and 74 years2. A perfect clientele for genealogical tourism and which, moreover, has a high level of computer literacy. Genealogical searches begin mainly on the Web.

Among the physical places, the most famous stop is the Ellis Island immigration museum in New York, inaugurated in 1990, where, from the day of its opening, it is possible to carry out searches via computer.

Brazil

“Between 1875 and 1935 it is estimated that about 1.5 million Italians entered Brazil, with a peak of greater intensity between 1880 and 1930. Although the Italians in Brazil are estimated at 23 million, the tourist proposals for this category in Italy (see Brazil Tourism Office in Rome) or in Brazil, are still rare “. An offer was not organized with products specifically reserved for Italian genealogical tourists.

The natives Italians are estimated at 14% of the total population of Brazil. They arrived en masse starting from 1875, especially in the Rio Grande do Sul. Between 1875 and 1914, between 80,000 and 100,000 Italians arrived, coming mainly from the provinces of Vicenza, Treviso, Verona and Belluno. Too often, however, the Italian settlement is almost forgotten. Italian, for example, was the colonization of the town of Orleans in the state of Santa Catarina, with its Immigration Museum, where Italian memories mingle with those of other European nationalities. In the same State, also of Italian origin is Criciúma, 185,506 inhabitants in 2007, one of the richest cities. His name is not Italian, but it is that of a local cane. But it was founded in 1880 by families from the provinces of Belluno, Udine, Vicenza and Treviso. The cultural initiative Caminhos de Pedra is worthy of note.

Europe

Internal immigration and new immigration from external countries do not produce, for the moment at least, genealogical tourism flows as relevant as those coming from overseas. Among the many “alternative” flows, mention should be made of those of the Germans towards Lithuania visiting the lands from which their families were hunted; those of Romanian emigrants returning to the Maramureç region, in Romania itself, to make a holiday; the same practice is used by European Moroccans who return home as tourists because life is cheaper there; the Turks living in Germany who are visited by their relatives; finally, those from France who report Italians in our country and those of Italians who have moved to work in the industrial triangle and who return to the South during the summer.

Ireland

The myth of the return trip to Ireland has been fed since the 1950s by writers and filmmakers such as Sam Shepard, John Ford, Herman Boxer (director: H. BOXER, The irish in me, USA, International Color-Cudley Pictures 1959). The heroes of these stories are Americans of Irish descent, second, third and fourth generation who face the Atlantic crossing to get closer to an “original home”. They start to discover their identity, travel the land of their ancestors, reinforce their sense of belonging and within this experience enrich their “memory”. The sentiments expressed by the protagonists of these artistic and literary works, today, unite thousands of anonymous travelers every year.

The agencies specialized in genealogical tourism thrive. The famous Lynott tours promises that in one month it will analyze the documents in the archives and send a detailed report and a map with the places to visit directly to overseas customers: the cost of the service is around 80 euros and the possibility of organize a totally tailor-made holiday.

Scotland

The Scottish genealogical tourists distinguish themselves from the others for their strong bond towards the clan: not a simple genealogy research of the family; moreover, the main motivation lies in the moral obligation to pay a debt of gratitude to the ancestors.

A mixed public and private committee was formed in which the board of the Ayrshire and Arran Tourism Industry Forum merged, local groups of family history enthusiasts, a company specialized in genealogical research, libraries, the regional tourism agency, the Local university and an expert in local history. The two main objectives identified were: to verify the level of preparation of the main tour operators; to quantify the demand for genealogical tourism for the area of Ayrshire and Arran. The methodology for achieving the first objective was: a survey through call centers on local tour operators; a further questionnaire to be submitted this time to taxi drivers (the first point of contact for tourists who visit this area). The investigations highlighted an information gap that was filled with the following actions: appropriate information leaflets at the points where research on ancestors was carried out; a video to educate the public relations workers of these structures to the needs of the new public; a web portal of family history inserted into the existing local tourism portal.

The proposed itineraries include the visit of “intentional monuments” (sites linked to the “great story of Scottish history), and of” unintentional “monuments, linked to the” small family history “, such as the tombs of the ancestors in the cemeteries or the ruins of the old houses that belonged to the family. In addition to places connected to the memory of the past, these trips can also include moments related to the present and research and the meeting with distant relatives of family branches left in the country of origin: the discovery of “new cousins” is identified as one of the maximum aspirations and satisfactions of the whole journey.

Italy

In Italy, unlike the countries surveyed so far, root tourism has never really been considered as an object of scientific research, nor as a real resource to invest in, even though there are many people who go there every year. in Italy because they are linked by relationships of kinship or simply inspired by the desire to know the places where their origins reside. This is also demonstrated by the almost total absence of official statistics that testify to the presence of this phenomenon on our territory.

Sporadic news appeared in recent years in the press, a poor institutional commitment and punctuated by initiatives sometimes valuable but always few and in any case lacking in coordination. A tourism, that genealogy, abandoned to small private initiatives consisting of associations and small farms of which we have found track on the web. The ‘tourist of the roots’ who travels for the first time in Italy is interested in visiting the main cities of art and the most famous tourist attractions and of course knowing the place where his ancestors were born, in which to be enchanted by the beauties of minor Italy.

Cultural impact

Return visits play an important role in the migratory experience and represent a fundamental aspect of the life of the emigrant. Embracing such a perspective requires the reconceptualization of numerous concepts related to the study of emigration, in particular theories on cultural transmission and the relationship between identity, ethnicity and territory. Therefore, emigration is not a process that ends with the establishment of the first generation, but rather as an interweaving of links and relations with the country of origin that persist after the settlement and which continue to influence subsequent generations.

Return journeys also call into question the very concept of settlement, if by settlement we mean the exclusive identification with the country of adoption. In fact, “it is possible to show that the emigrants who often return to the country do not feel they belong to a single territory, but feel loyal to both. This is a problem that can not be explained by the paradigms of classical studies on emigration, since it is part of a discourse on the search for an identity, recognized as a psychological need of the individual “.

The tourist of the roots lives an inner conflict made of love and hate. The country he goes to is still his homeland but his closest family lives in the adopted country. The new country is the anchor of the family while the ancient homeland is a place of lost memories: you do not really feel at home in any of the two countries and experience a consequent sense of disorientation. The continuous identification with the country of origin envelops him in a spiral of nostalgia that makes him return. For him the hearth is a “fulcrum” that moves continuously without ever stopping.

Whether the returns come from a feeling of obligation towards the original community or for other personal reasons, the continuous shuttling between the two countries makes them similar to the pilgrims. Using this metaphor, return visits are a kind of secular pilgrimage, a cultural renewal for the first generation and a transformation for the following generations. The native country becomes a sort of secular sanctuary, a point of orientation for its identity.

The return visit, often yearly, is perhaps the integrating factor of his life for the emigrant. It follows that the emigrants feel more “home” during the journey between the two “houses”: the migratory movement between two countries in itself creates a sense of homeland. For this reason, visits to the country are constitutive of the identity of the emigrant.

The return visits of first generation and subsequent immigrants also produce an impact on the identity of those who remained, in particular the residents who dialogue, host and compare themselves with genealogical tourists: getting in touch with other ways of experiencing ‘national identity, in our case, Italianness, also causes them to deterritorialize their identity. At the same time, it is the natives, with their welcoming attitude, who hold the power to make tourists feel part of the nation visited, a sort of extended family.

Some scholars support the theory that identity in contemporary society is deterritorialized and that this is the condition of post-modernity. Others, in contrast with this point of view, affirm that cultures belong fundamentally to social relations and networks of relationships: the less people are in one place and the more tenuous the link between culture and territory becomes. Both theses are valid, provided that the territory is interpreted also as a place of imagination. Diasporic identities like that of tourists descended from ancient migrants are by definition deterritorialized but are rooted in the imaginary of the territory. The territory assumes a central importance, and continues, for the construction of identity.

“The identification of the complex and overlapping social realities, which cause identity problems for transnational emigrants, contradicts the homogenizing tendencies within the processes of globalization”. This is why emigrants have the impression of having no country, of belonging neither to the native country nor to the elective one. Now it is clear why the “homeland” of the emigrant can become a destabilized “hub” and cause a deterritorialized identity.

The meanings of home, home and country – effectively synthesized by the Anglo-Saxon culture in the word home -, exist in the imaginary and are reworked through the experiences of return journeys and stays in the country. This feeling at home of the emigrants of first or subsequent generations only while they make the journey – going to that sanctuary that is the home country, and returning to life as pilgrims in the land that hosts them – depends more on a sense of belonging to the place that from the absence of a territory and perhaps it is the children that bind them to the territory preventing them from becoming rootless nomads.

Economic impact

According to estimates by the Scalabrinian Fathers, the Italians in the world are eighty million, of which twenty-seven million in Brazil, twenty million in Argentina, seventeen million in the United States, more than one million in Uruguay where they represent 35% of the total population, etc.

Conscious of these figures, ENIT, in the annual report documents related to these countries, highlights the tourist opportunities arising from the return tourism and suggests considering the possibility of adopting appropriate strategies to exploit this resource. Perhaps, it is not enough for Italy to point to a generic return tourism; it should instead focus on genealogical tourism communicated in terms of ‘journey to the roots’ and based on genealogical research.

In this way we could maximize and multiply the positive economic impact deriving from the propensity of these tourists to travel in seasonally adjusted, to spend more than others to buy local products, to stay for longer periods, in contrast with the current contemporary concept vacation city break: more stays and less time.

Genealogical tourism does not fear competition from other countries. Those who cross the ocean, perhaps having to wait to get an entry visa, probably will want to visit the major art cities of other states but will be the cities, villages, events, fashion, design and popular culture of territory of its origins to catalyze its attention.

The positive effects also affect the country of origin when tourist communication is disseminated through foreign media, or when international cooperation agreements are signed for archival research; but it is mainly in the country of origin that the greatest benefits are obtained: the many travel agencies in crisis, due to the spread of online bookings, could re-qualify and propose to organize genealogical tourism trips with on-site assistance; new professions of ‘tour operator returning to the roots’ could arise; graduates, for example in archives or cultural heritage could be employed in the tasks of assistant to genealogical research in the State Archives and ecclesiastics.

The greater identity pride will produce in the country of habitual residence a request for products from the ‘country of roots’ and a consequent opening of shops, pubs, restaurants and employment in cultural associations, institutions that protect the language etc.; and, in return, the increase in exports of typical products.

Italian regional legislation

The Veneto Region with the Regional Law 2/2003, in art. 12, provides that the administration promotes, through funding, the organization of stays in the region of foreign nationals residing abroad. Residents of Venetian origin resident abroad are eligible for funding, in order to give them the opportunity to get to know their places of origin and re-enter in direct contact with the Veneto region, culture and society. Sardinia reserves economic benefits for stays of those born in Sardinia residing abroad while in Abruzzo a similar proposal has been put forward but also intended for their children.

Conclusions

The tourism of the roots, a mainly international tourism but that is directed towards the minor and often unknown centers, could favor the birth of new destinations and contribute to the economic development of some territories: it increases the consumption of products and the use of infrastructures and services locals; it is a sustainable tourism because it does not invade areas where tourism already has a significant impact; on the contrary, it aims at enhancing those small towns where the presence of visitors could trigger virtuous processes of rethinking the territory that in this case would be subtracted from oblivion and abandonment.

Source from Wikipedia