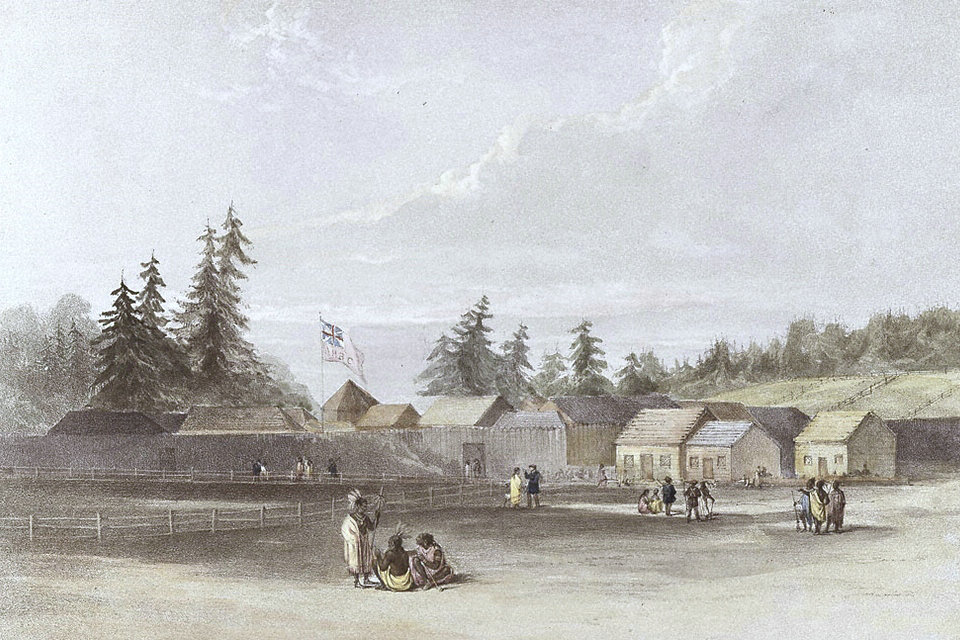

Fort Vancouver was a 19th-century fur trading post that was the headquarters of the Hudson’s Bay Company’s Columbia Department, located in the Pacific Northwest. Named for Captain George Vancouver, the fort was located on the northern bank of the Columbia River in present-day Vancouver, Washington. The fort was a major center of the regional fur trading. Every year trade goods and supplies from London arrived either via ships sailing to the Pacific Ocean or overland from Hudson Bay via the York Factory Express. Supplies and trade goods were exchanged with a plethora of Indigenous cultures for fur pelts. Furs from Fort Vancouver were often shipped to the Chinese port of Guangzhou where they were traded for Chinese manufactured goods for sale in the United Kingdom. At its pinnacle, Fort Vancouver watched over 34 outposts, 24 ports, six ships, and 600 employees. Today, a full-scale replica of the fort, with internal buildings, has been constructed and is open to the public as Fort Vancouver National Historic Site.

Located on the north bank of the Columbia River, in sight of snowy mountain peaks and a vibrant urban landscape, this park has a rich cultural past. From a frontier fur trading post, to a powerful military legacy, the magic of flight, and the origin of the American Pacific Northwest, history is shared at four unique sites. Discover stories of transition, settlement, conflict, and community.

Discover a place with a deeply layered history. Nestled along the Columbia River in the heart of the Portland-Vancouver Metropolitan Area, Fort Vancouver National Historic Site has for generations been a hub for the exchange of ideas, values, and beliefs between diverse peoples.

Long before European contact, the Chinookan people of the area hunted, gathered, and traded, hosting visitors traveling from every direction. Epidemics and the British colonial settlement of Fort Vancouver irrevocably changed this, but created a unique community which merged multiple ways of understanding and responding to the world.

Fort Vancouver was a surprising place: it was a headquarters and primary supply depot for fur trading operations, but employed more people at agriculture than any other activity. It was a large corporate monopoly that kept order and stability by employing many different ethnic groups. It was a British establishment, but the primary languages were Canadian French and Chinook Jargon. It represented British territorial interests, yet made American settlement in the Pacific Northwest possible. Even those who wished it gone praised the hospitality and assistance they found there.

The subsequent U.S. Army post at the site, Vancouver Barracks, was equally surprising. Its goal was to provide for peaceful settlement of the Oregon Country, yet it did so, in part, by battling and dispossessing the established inhabitants. For more than 150 years it housed and supported thousands of soldiers and their families, yet it also incarcerated Native American families and Italian prisoners of war. Through two world wars, conflict abroad bred innovation and industry here.

Today, it is a national park where we help visitors make personal connections to the people, places, stories, and collections of Fort Vancouver National Historic Site.

History:

During the War of 1812, the Pacific Northwest was a distant region of the conflict. Two rival fur trading outfits, the Canadian North West Company (NWC) and the American Pacific Fur Company (PFC), had until then both operated in the region peaceably. Funded largely by John Jacob Astor, the PFC operated without many opportunities for military defense by the United States Navy. News of the war and of a coming British warship put the American company into a difficult position. In October 1813, management met at Fort Astoria and agreed to liquidate its assets to the NWC. The HMS Racoon arrived the following month and in honor of George III of the United Kingdom, Fort Astoria was renamed to Fort George.

In negotiations with American Albert Gallatin throughout 1818, British plenipotentiary Frederick John Robinson was offered a proposition for a partition that would have, as Gallatin stated, “all the waters emptying in the sound called the Gulf of Georgia.” Frederick Merk has argued the definition used by the negotiators of the Gulf of Georgia included the entirety of the Puget Sound, in addition to the Straits of Georgia and Juan de Fuca. This would have given the United Kingdom the most favorable location for ports north of Alta California and south of Russian America. Robinson didn’t agree to the proposal and subsequent talks didn’t focus on establishing a permanent border west of the Rocky Mountains.

The Treaty of 1818 made the resources of the vast region were to be “free and open” to citizens from either nation. The treaty wasn’t made to combine American and British interests against other colonial powers in the region. Rather, the document states that the joint occupancy of the Pacific Northwest was intended to “prevent disputes” between the two nations from arising. In the ensuing years, the North West Company would continue to expand its operations in the Pacific Northwest. Skirmishes with its major competitor, the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC), had already flared into the Pemmican War. The end of the conflict in 1821 saw the NWC mandated by the British Government to merge into the HBC.

Throughout 1825 and 1826, British officials would continue to offer Americans partition plans for the Pacific Coast of North America. These largely originated in part from correspondence with the NWC and later HBC. The border would continue to extend west on the 49th parallel to the Rocky Mountains, where the Columbia (and some times the Snake River) would be used as the border until it reached the Pacific Ocean. Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs George Canning has been appraised by later historians most supportive British Foreign minister in securing a border along the Columbia. United States Secretary of State Henry Clay had given instructions the American plenipotentiaries to offer a partition of the Pacific Northwest along the 49th parallel to the Pacific Ocean. The difference in the two considered plans were too much to solve, making the diplomats put off a formal colonial division once more.

In the early 1820s a general reorganization of all NWC properties, now entirely under HBC management, was overseen directly by Sir George Simpson. The newly established Columbia District needed a more suitable headquarters than Fort George at the mouth of the Columbia. Simpson was instrumental in the establishment of Fort Vancouver. Using the HBC position that any settlement of the Oregon boundary dispute would place the border placed along the Columbia; Simpson selected a location situated opposite from the mouth of the Willamette River. This expanse was an open and fertile prairie that was outside the flood plain and had easy access to the Columbia.

Places:

Featuring a reconstructed British fur trading fort, a historic U.S. Army Post, one of the oldest continuously operating airfields, a historic house designated as one of the first national historic sites in the west, and the site of one of the largest multicultural villages in the Pacific Northwest, the concept of place is core to Fort Vancouver National Historic Site.

Fort Vancouver

The fort was substantial. The palisades that protected it were 750 feet (230 m) long, 450 feet (140 m) wide and about 20 feet (6.1 m) high. Inside, there were 24 buildings, including housing, warehouses, a school, a library, a pharmacy, a chapel, a blacksmith, plus a large manufacturing facility. The Chief Factor’s residence was in the center of Fort Vancouver was two stories tall. Inside was a dining hall where company clerks, traders, physicians, and others of the gentleman class would dine with the supervising Chief Factor. In general, the entirety of the Chief Factor’s House and its meals were typically barred for general laborers and fur trappers. After dinner the majority of these gentlemen would relocate to the “Bachelor’s Hall” to “amuse themselves as they please, either in smoking, reading, or telling and listening to stories of their own and others’ curious adventures.”

The London-based Hudson’s Bay Company established Fort Vancouver in 1825 to serve as the headquarters of the Company’s interior fur trade. The first Fort Vancouver was located on the bluff to the northeast of the fort’s current location, where it was relocated in 1829. The fort served as the core of the HBC’s western operations, controlling the fur business from Russian Alaska to Mexican California, and from the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Ocean. Vancouver was the principal colonial settlement in the Pacific Northwest, and a major center of industry, trade, and law.

With high demand from Europe for fur based textiles in the early 19th Century, the Hudson’s Bay Company was forced to expand its fur trade operations across North America to the Pacific Northwest. Prior to the establishment of Fort Vancouver, the Hudson’s Bay Company’s largest westward fort was Fort William in present day Ontario, which the company gained through it’s merger with the North West Company. From its establishment, Fort Vancouver was the regional headquarters of the Hudson’s Bay Company’s fur trade operations in the Columbia District. The territory it oversaw stretched from the Rocky Mountains in the East to the Pacific Ocean in the West, and from Sitka, Alaska in the North to San Francisco in the South. Fur trappers would bring pelts collected during the winter to the fort to be traded in exchange for company credit. The credit, issued by the company clerks, could be used to purchase goods in the fort’s trade shops. Furs from throughout the Columbia District were brought to Fort Vancouver from smaller Hudson’s Bay Company outposts either overland, or by water via the Columbia River. Once they were sorted and inventoried by the Company’s clerks, the furs were hung out to dry in the fur storehouse, a large two story post on sill type building located within the walls of the fort. After the furs had been processed, they were mixed, weighed into 270 pounds (120 kg) bundles, and packed with tobacco leaves as an insecticide. The 270 pounds (120 kg) bundle of furs would be placed in a large press and wrapped in elk or bear hide to create overseas fur bales. The large 270 pounds (120 kg) bales were then placed on boats on the Columbia River for shipment to London via the Hudson’s Bay Company trade routs. The furs would then be auctioned off to textile manufacturers in London. A large demand came from hatters who produced popular beaver felted hats.

The Village

The significance of the workforce employed by Fort Vancouver has often been overlooked, and so have the grounds they inhabited.

Fort Vancouver could not have fulfilled its role as the headquarters of the Columbia Department without its employees.

Vancouver Barracks

Known by a variety of names, including Camp Vancouver (1849-1850), Columbia Barracks (1850-1853), Fort Vancouver (1853-1879), and finally Vancouver Barracks (1879 to present), the United States Army established this post in 1849 on a low ridge above the Hudson’s Bay Company’s Fort Vancouver to provide for peaceful American settlement of the Oregon Country.

As the first U.S. Army post in the Pacific Northwest, Vancouver Barracks served as a major headquarters and supply depot during the Civil War and Indian War eras. Some seventy officers who attained the rank of general were stationed here, including Ulysses S. Grant, Philip H. Sheridan, George B. McClellan, George Pickett, George Crook, Oliver O. Howard, and Nelson Miles. Later, it served as a recruitment, mobilization and training facility for the Spanish-American War, the Philippine War, and other foreign engagements.

Today, Vancouver Barracks remains one of the nation’s most historic military posts, and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Although the boundaries and surrounding scenery have changed significantly, the central core of the original Vancouver Barracks remains. Thanks, in part, to more than 160 years of Army presence and stewardship, this significant place in our nation’s history is well prepared for transfer to the National Park Service, where it will be preserved in perpetuity for the enjoyment, education, and inspiration of future generations.

Agricultural:

At its inception, Governor George Simpson wanted the fort to be self-sufficient as food was costly to ship. Fort staff typically maintained one year’s extra supplies in the fort warehouses to avoid the disastrous consequences of ship wrecks and other calamities. Fort Vancouver eventually began to produce a surplus of food, some of which was used to provision other HBC posts in the Columbia Department. The area around the fort was commonly known as “La Jolie Prairie” (the pretty prairie) or “Belle Vue Point” (beautiful vista). In time, Fort Vancouver would diversify its economic activities beyond fur trading and begin exporting agricultural foodstuffs from HBC farms, along with salmon, lumber, and other products. It developed markets for these exports in Russian America, the Kingdom of Hawaii, and Mexican California. The HBC opened agencies in Sitka, Honolulu, and Yerba Buena (San Francisco) to facilitate such trade.

Restoration:

Because of its significance in United States history a plan was put together to preserve the location. Fort Vancouver was declared a U.S. National Monument on June 19, 1948, and redesignated as Fort Vancouver National Historic Site on June 30, 1961. This was taken a step further in 1996 when a 366-acre (1.48 km2) area around the fort, including Kanaka Village, the Columbia Barracks and the bank of the river, was established as the Vancouver National Historic Reserve maintained by the National Park Service. It is possible to tour the fort. Notable buildings of the restored Fort Vancouver include a bake house, where Hardtack baking techniques are shown, a Blacksmith shop, a carpenter shop and its collection of carpentry tools, and the kitchen, where daily meals were prepared.