Environmental economics

Environmental economics is a sub-field of economics that is concerned with environmental issues. It has become a widely studied topic due to growing concerns in regards to the environment in the 21th century. Environmental Economics undertakes theoretical or empirical studies of the economic effects of national or local environmental policies around the world. Particular issues include the costs and benefits of alternative environmental policies to deal with air pollution, water quality, toxic substances, solid waste, and global warming.

Environmental economics is distinguished from ecological economics in that ecological economics emphasizes the economy as a subsystem of the ecosystem with its focus upon preserving natural capital. One survey of German economists found that ecological and environmental economics are different schools of economic thought, with ecological economists emphasizing “strong” sustainability and rejecting the proposition that natural capital can be substituted by human-made capital.

Economical Environmental Economics

Basics

The Economics of Environmental Economics deals with the consideration and investigation of the relationship between economy and the natural environment of man. For economic analysis, environmental goods only become relevant from the point of view of scarcity. In a market-based system with predominantly private goods, environmental goods are consumed directly in consumption or indirectly through use in the production process. Scarcity calls for efforts to restore used environmental goods, to limit the consumption of these environmental goods or to reduce factor inputs that pollute the environment. At this point, the problem of allocation picks up and the question arises of an appropriate distribution of environmental goods.

Initial problem

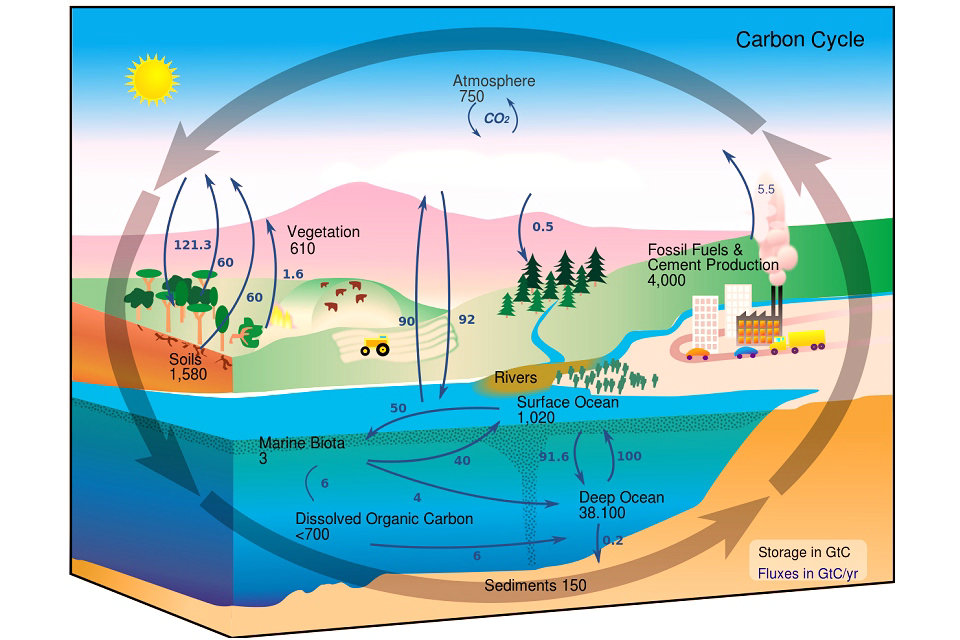

The solution of the allocation problem requires the knowledge of some properties of environmental goods. The starting point of reflection on the causes of environmental problems is the contradiction that natural resources (such as clean air, pure water, etc.) on the one hand through the increasing environmental pollution to a scarce have become so not (any longer) Unlimited available Good, on the other hand simultaneously but still have the character of free or public goods. Against this background, wherever the use of environmental services is not regulated, it threatens its continuous exploitation by overuse, which therebystimulated and encouraged that, due to the nature of environmental services as a public good, there is the possibility of externalising costs or taking so-called ” free rider positions “. There are also additional burdens imposed on individuals of an economy by the economic activities of other economic agents. This is called “external effects”. In the production sector, these lead to a deviation between private and social marginal costs, by influencing the production possibilities of other producers. External effectsRun partly past the regular markets and are not integrated into the price signals (“internalized”). Damage occurs in many ways: in the form of known pressures such as the pollution of waters and the eradication of entire plant and animal species, but also in the form of incompletely clarified relationships such as the unclear consequences of the greenhouse effect or an increase in cancer in stress areas.

Solutions

The possibility of solving environmental problems is obvious in this perspective: If environmental services can be made economically efficient through their integration into the market, that is, through neglect, their scarcity, then the incentives previously misdirected towards misuse and overuse will become one gentle, economical handling of natural resources. In other words, only when market prices, as Ernst Ulrich von Weizsäcker puts it, have the full ecological truthsay, becomes aware of the scarcity and preciousness of natural resources and becomes the subject of everyday economic decisions. Overall, internalisation should ensure the efficiency of the market mechanism with an efficient allocation result even if external effects are present.

Instruments that provide the required market integration of natural resources are called market-oriented instruments of environmental policy. Examples include eco- taxes, steering fees or the trading of emission rights. In contrast to the price control on the basis of the ecotax and the steering charges, the approach of the emission certificates is based on quantity control. The advantage of such solutions is the dynamic economic incentive for companies and households to carry out further environmental protection measures in the interests of their own cost savings, at least as long as the marginal costsenvironmental protection does not exceed the marginal cost of additional environmental impact (which can be controlled by a tightening of tax rates or a tightening of pollution rights). Relevant in this context is the Coase Theorem, which investigates the possibility that the offender and the victim negotiate with each other about the level of the external effect. The prerequisite for an economically efficient internalization of external effects through negotiations between two parties is a clear assignment of property rights to the environmental goods, which conveys the external effect. However, such regulatory approaches to environmental policy (laws and regulationsthat z. For example, certain behaviors or state limits) are only accepted where they are used for short-term environmental protection (eg CFC ban), but otherwise assessed as inefficient with the reference to the lack of dynamic environmental protection incentives and therefore rejected. Regulatory interventions will continue to be allowed if the transaction costs for implementing a market-based solution exceed the hoped-for efficiency gain.

The goal of neoclassical environmental economics is not to reduce environmental pollution, but to limit it to its optimum. This optimum of environmental impact lies where the marginal utility of environmental pollution justifies the border damage.

Specific Tasks

Economically oriented environmental economics is usually understood as part of welfare economics. Environmental economics can thus be classified as a problem-specific extension of the neoclassical mainstream of economics. A key task is the development of instruments for the market integration of natural resources in the decision-making processes for public and private environmental interventions.

Another task is the evaluation of programs and measures with environmental impacts from the point of view of economic efficiency (” environmental assessment “). The central analytical tool for this task is the most environmentally advanced economic cost-benefit analysis (Engl. Cost-benefit analysis). The Environmental Economic Accounts (UGR) of the German Federal and State Statistics could in principle assume similar analytical tasks. A significant extension of the environmental economic cost-benefit analysis compared to the general economic cost-benefit analysis is the use of Total Economic ValueApproach to determining intervention, project and program sequences.

Topics and concepts

Market failure

Central to environmental economics is the concept of market failure. Market failure means that markets fail to allocate resources efficiently. As stated by Hanley, Shogren, and White (2007) in their textbook Environmental Economics: “A market failure occurs when the market does not allocate scarce resources to generate the greatest social welfare. A wedge exists between what a private person does given market prices and what society might want him or her to do to protect the environment. Such a wedge implies wastefulness or economic inefficiency; resources can be reallocated to make at least one person better off without making anyone else worse off.” Common forms of market failure include externalities, non-excludability and non-rivalry.

Externality

An externality exists when a person makes a choice that affects other people in a way that is not accounted for in the market price. An externality can be positive or negative, but is usually associated with negative externalities in environmental economics. For instance, water seepage in residential buildings happen in upper floor affect the lower floor. Another example concerns how the sale of Amazon timber disregards the amount of carbon dioxide released in the cutting.[better source needed] Or a firm emitting pollution will typically not take into account the costs that its pollution imposes on others. As a result, pollution may occur in excess of the ‘socially efficient’ level, which is the level that would exist if the market was required to account for the pollution. A classic definition influenced by Kenneth Arrow and James Meade is provided by Heller and Starrett (1976), who define an externality as “a situation in which the private economy lacks sufficient incentives to create a potential market in some good and the nonexistence of this market results in losses of Pareto efficiency”. In economic terminology, externalities are examples of market failures, in which the unfettered market does not lead to an efficient outcome.

Common goods and public goods

When it is too costly to exclude some people from access to an environmental resource, the resource is either called a common property resource (when there is rivalry for the resource, such that one person’s use of the resource reduces others’ opportunity to use the resource) or a public good (when use of the resource is non-rivalrous). In either case of non-exclusion, market allocation is likely to be inefficient.

These challenges have long been recognized. Hardin’s (1968) concept of the tragedy of the commons popularized the challenges involved in non-exclusion and common property. “Commons” refers to the environmental asset itself, “common property resource” or “common pool resource” refers to a property right regime that allows for some collective body to devise schemes to exclude others, thereby allowing the capture of future benefit streams; and “open-access” implies no ownership in the sense that property everyone owns nobody owns.

The basic problem is that if people ignore the scarcity value of the commons, they can end up expending too much effort, over harvesting a resource (e.g., a fishery). Hardin theorizes that in the absence of restrictions, users of an open-access resource will use it more than if they had to pay for it and had exclusive rights, leading to environmental degradation. See, however, Ostrom’s (1990) work on how people using real common property resources have worked to establish self-governing rules to reduce the risk of the tragedy of the commons.

The mitigation of climate change effects is an example of a public good, where the social benefits are not reflected completely in the market price. This is a public good since the risks of climate change are both non-rival and non-excludable. Such efforts are non-rival since climate mitigation provided to one does not reduce the level of mitigation that anyone else enjoys. They are non-excludable actions as they will have global consequences from which no one can be excluded. A country’s incentive to invest in carbon abatement is reduced because it can “free ride” off the efforts of other countries. Over a century ago, Swedish economist Knut Wicksell (1896) first discussed how public goods can be under-provided by the market because people might conceal their preferences for the good, but still enjoy the benefits without paying for them.

Valuation

Assessing the economic value of the environment is a major topic within the field. Use and indirect use are tangible benefits accruing from natural resources or ecosystem services (see the nature section of ecological economics). Non-use values include existence, option, and bequest values. For example, some people may value the existence of a diverse set of species, regardless of the effect of the loss of a species on ecosystem services. The existence of these species may have an option value, as there may be the possibility of using it for some human purpose. For example, certain plants may be researched for drugs. Individuals may value the ability to leave a pristine environment to their children.

Use and indirect use values can often be inferred from revealed behavior, such as the cost of taking recreational trips or using hedonic methods in which values are estimated based on observed prices. Non-use values are usually estimated using stated preference methods such as contingent valuation or choice modelling. Contingent valuation typically takes the form of surveys in which people are asked how much they would pay to observe and recreate in the environment (willingness to pay) or their willingness to accept (WTA) compensation for the destruction of the environmental good. Hedonic pricing examines the effect the environment has on economic decisions through housing prices, traveling expenses, and payments to visit parks.

Solutions

Solutions advocated to correct such externalities include:

Environmental regulations. Under this plan, the economic impact has to be estimated by the regulator. Usually this is done using cost-benefit analysis. There is a growing realization that regulations (also known as “command and control” instruments) are not so distinct from economic instruments as is commonly asserted by proponents of environmental economics. E.g.1 regulations are enforced by fines, which operate as a form of tax if pollution rises above the threshold prescribed. E.g.2 pollution must be monitored and laws enforced, whether under a pollution tax regime or a regulatory regime. The main difference an environmental economist would argue exists between the two methods, however, is the total cost of the regulation. “Command and control” regulation often applies uniform emissions limits on polluters, even though each firm has different costs for emissions reductions. Some firms, in this system, can abate inexpensively, while others can only abate at high cost. Because of this, the total abatement has some expensive and some inexpensive efforts to abate. Consequently, modern “Command and control” regulations are oftentimes designed in a way, which addresses these issues by incorporating utility parameters. For instance, CO2 emission standards for specific manufacturers in the automotive industry are either linked to the average vehicle footprint (US system) or average vehicle weight (EU system) of their entire vehicle fleet. Environmental economic regulations find the cheapest emission abatement efforts first, then the more expensive methods second. E.g. as said earlier, trading, in the quota system, means a firm only abates if doing so would cost less than paying someone else to make the same reduction. This leads to a lower cost for the total abatement effort as a whole.

Quotas on pollution. Often it is advocated that pollution reductions should be achieved by way of tradeable emissions permits, which if freely traded may ensure that reductions in pollution are achieved at least cost. In theory, if such tradeable quotas are allowed, then a firm would reduce its own pollution load only if doing so would cost less than paying someone else to make the same reduction. In practice, tradeable permits approaches have had some success, such as the U.S.’s sulphur dioxide trading program or the EU Emissions Trading Scheme, and interest in its application is spreading to other environmental problems.

Taxes and tariffs on pollution. Increasing the costs of polluting will discourage polluting, and will provide a “dynamic incentive,” that is, the disincentive continues to operate even as pollution levels fall. A pollution tax that reduces pollution to the socially “optimal” level would be set at such a level that pollution occurs only if the benefits to society (for example, in form of greater production) exceeds the costs. Some advocate a major shift from taxation from income and sales taxes to tax on pollution – the so-called “green tax shift.”

Better defined property rights. The Coase Theorem states that assigning property rights will lead to an optimal solution, regardless of who receives them, if transaction costs are trivial and the number of parties negotiating is limited. For example, if people living near a factory had a right to clean air and water, or the factory had the right to pollute, then either the factory could pay those affected by the pollution or the people could pay the factory not to pollute. Or, citizens could take action themselves as they would if other property rights were violated. The US River Keepers Law of the 1880s was an early example, giving citizens downstream the right to end pollution upstream themselves if government itself did not act (an early example of bioregional democracy). Many markets for “pollution rights” have been created in the late twentieth century—see emissions trading.

Tools of the environmental economy

The example of the Kyoto Protocol

The Kyoto Protocol is a typical illustration of the role of environmental economics: it is a matter of reconciling economic development with environmental constraints. The drafting of the protocol involved a group of specialists from different fields: meteorologists, industrialists, lawyers, etc. And we had to reconcile all the visions. From scientific data (the impact of a tonne of CO 2released into the air) and economic data (impact on growth), within a given legal framework (an international agreement), the environmental economy seeks to define an optimum situation (optimum of pollution) to be achieved and achieved. build a number of tools that will help achieve this goal.

The pollution optimum thus defined will be, by definition, removed from two other positions: that of the partisans of a hard ecology (or deep according to the literal translation of deep ecology) which will aim at canceling carbon emissions, and that of supporters of market ecology who think that public action is useless because the environment will naturally be included in prices. The position of the environmental economy is by nature a compromise.

Thus, the goal of returning in 2012 to a level of CO 25.2% below 1990 levels will be different in different countries. Some developing countries such as Brazil have no emission reduction target, with most developed countries reducing them. The case of France is particular since its objective negotiated in the framework of the sharing of the common objective of the European Union is the stabilization of its emissions in 2012 compared to their level of 1990.

Taxes, bonuses and rights markets to pollute

The state can intervene by regulating by setting a standard or a tax. Both must achieve the same pollution result if the company’s cleanup costs are known. In the case of the tax, the polluter pays a tax which will aim to compensate for the damage suffered by the pollutant. Apparently, the tax respects the polluter pays principle. Note that in France, a tax can not be assigned for a specific purpose, environmental taxes (with the exception of the TIPP) contribute to finance the entire budget of the State 4.

The second instrument is the bonus: either a premium for the modernization of the production apparatus or a non-polluter bonus. In the first case, the polluted is invited to pay a premium which must help the polluter to improve his installations and thus to less pollute: it is the functioning of the PMPOAin France. In the second case, we congratulate companies that do not pollute, or less than others, by paying them a premium. When the bonus mechanism is coupled to that of the tax, the polluter pays principle is generally respected: those who pollute pay a tax that is paid to them in the form of a bonus which will allow the public to guide the modernization. On the other hand, if it is the taxpayer who pays, the polluter pays principle is absolutely not respected; it is however this device that one finds frequently.

The last solution of this type is the establishment of a market of rights to pollute. This solution, which has been prefigured since the beginning of industrialization, 5 has been formalized by Ronald Coasein the 1960s: for Coase, externalities do not mark the failure of economic theory, but only the absence of a right of ownership over the environment. Nature does not belong to anyone and that is the problem. The recommended solution is to reintroduce a property right to the environment itself (as an identifiable material resource such as a watercourse). The property can be attributed to either the polluted or the polluter. Coase then shows that, regardless of the initial owner of the property rights, a direct negotiation between polluter and pollutant will always result in the same final equilibrium, optimal in the sense of Pareto. The notable advantage of this solution compared to the previous ones is that the tax system, and therefore the taxpayers do not intervene. However,Coase theoremThe fundamental assumption is that there are no transaction costs (which is not an assumption when there are a large number of parties involved). The operational solution inspired by the need to define property rights is truly the market of rights to pollute or market of tradable permits, but more explicitly “market of tradable emission allowances”. Companies exchange, that is to say, sell and buy, permits that give them the right to emit for example sulfur (see our example of electricity production). These permits are distributed (free of charge or auctioned) by the public authorities who set the number according to the rationing they want to impose on the polluters. Those who can reduce their emissions easily and at low cost will find it more profitable to use fewer permits and resell the surplus in the market. Those who, on the contrary, have higher costs of reducing their emissions will find it more profitable to buy additional emission permits. The market allows the exchanges between these different polluters and the confrontation of the supply and the demand of license results in the formation of a price of equilibrium of the market. If the public authorities wish to reinforce the constraint on polluters, they can reduce the number of permits: their scarcity leads to higher prices, and more and more companies are encouraged to modernize their installations. TheCoase’s theorem and the one on the tradable permit markets (see also Carbon Exchange).

Law and regulatory instruments

A second major category of instruments is the “regulatory route”, used by the legislator to produce laws and norms limiting or prohibiting the degradation of natural resources and certain pollution, for example by setting maximum emission standards.

Promulgating laws may seem easy, but some pitfalls exist: will the laws be relevant (question of legal certainty)? Can we control the application? (Sometimes the state is not able to bear these control costs, as it may not be able to control tax evasion; the tax may seem easier to implement, but it must also press the law). In addition, regulatory intervention is generally frowned upon by the Liberals who refuse the “hand of the state ” for the benefit of the market.

Defining ” good laws ” and monitoring their actual application requires states to have adequate observatories and monitoring tools. The production of relevant indicators for public policy also involves access to reference data and data relevant environmental (status indicators, response pressure).

For this the European Union relies on the Amsterdam Treaty (whose objectives include environmental efficiency) and on the Lisbon Strategy reviewed by the Göteborg European Council in 2001 which supported its sustainable development objectives, pushing more comprehensive environmental regulation, via the white papers, many European directives (water framework directive, energy directive and sectoral policies…). The European Environment Agency, located in Copenhagen, is holding aenvironmental data registry in support of decisions. Directive 2003/98 / EC provides a framework to ensure that Member States make available the data of public services, to the extent that national laws allow. The Denmark and the United Kingdom launched the project MIReG to provide the reference data in electronic form for the development of a comprehensive policy.

Today, two-thirds of new legislation in Europe comes from European regulations and directives, which are developed according to sustainable development criteria. They include access to environmental information, environmental labeling, the right of the public and markets to have information on the environmental policy of large companies. Another important theme is the protection, management and restoration of biodiversity and natural habitatswhich relies on impact studies, compensatory measures, but also on the notion of fault, prejudice and environmental crime and the criminal law of the environment, environmental and climate research, certain exemptions, the taking account of the environment in the face of competition law, social and environmental responsibility, the integration of environmental clauses in public procurement 6, ecodesign, chemicals management (Reach, waste and site regulations Polluted soils and sediments, pesticides, GMOs, nanotechnologies, endocrine disruptors, etc. The law has recently evolved by integrating the carbon market andgreenhouse gas quotas, and perspectives are opened on the economic valuation of nature.

Evaluation of public policies

Beyond their mere implementation and the choice of one or another of these policies, the environment economy must also offer instruments for evaluating these same policies. Many studies have shown that the combination of instruments rarely leads to an optimal situation.

This assessment should be conducted regularly and as far as possible, the environmental associations must participate. Despite the oppositions faced by the antinomic economy of the environment, these associations must be able to speak on an equal footing with companies, public authorities and experts: the integration of environmental economists into their environment. team becomes indispensable.

One of the methods used for environmental monitoring is the model Pressure State Response of the OECD, or derivatives models used in the UN or the European Environment Agency.

Environmental Economics Business

Operational environmental economics examines the effects of a company’s environmental impact and its economic success. In addition to the question of how the fulfillment of legal requirements or environmental goals can be managed as cost-effectively as possible, environmental economics also investigates the extent to which a company can purposefully exploit ecological aspects as a competitive advantage. Furthermore, the environmental economy should show a company the possibilities to meet the environmental requirements of the market, the state and society.

Delineation to the Ecological Economy

Scientists who reject neoclassical orientation tend to prefer ecological economics approaches. In practical work, however, there is a continuum between the two schools or an overlap of the scientists involved. Some scientists also do not use the term in contrast to the neoclassical environmental economics, but as a generic term, under which the resource and environmental economics are summarized.

Relationship to other fields

Environmental economics is related to ecological economics but there are differences. Most environmental economists have been trained as economists. They apply the tools of economics to address environmental problems, many of which are related to so-called market failures—circumstances wherein the “invisible hand” of economics is unreliable. Most ecological economists have been trained as ecologists, but have expanded the scope of their work to consider the impacts of humans and their economic activity on ecological systems and services, and vice versa. This field takes as its premise that economics is a strict subfield of ecology. Ecological economics is sometimes described as taking a more pluralistic approach to environmental problems and focuses more explicitly on long-term environmental sustainability and issues of scale.

Environmental economics is viewed as more pragmatic in a price system; ecological economics as more idealistic in its attempts not to use money as a primary arbiter of decisions. These two groups of specialists sometimes have conflicting views which may be traced to the different philosophical underpinnings.

Another context in which externalities apply is when globalization permits one player in a market who is unconcerned with biodiversity to undercut prices of another who is – creating a race to the bottom in regulations and conservation. This, in turn, may cause loss of natural capital with consequent erosion, water purity problems, diseases, desertification, and other outcomes which are not efficient in an economic sense. This concern is related to the subfield of sustainable development and its political relation, the anti-globalization movement.

Environmental economics was once distinct from resource economics. Natural resource economics as a subfield began when the main concern of researchers was the optimal commercial exploitation of natural resource stocks. But resource managers and policy-makers eventually began to pay attention to the broader importance of natural resources (e.g. values of fish and trees beyond just their commercial exploitation). It is now difficult to distinguish “environmental” and “natural resource” economics as separate fields as the two became associated with sustainability. Many of the more radical green economists split off to work on an alternate political economy.

Environmental economics was a major influence on the theories of natural capitalism and environmental finance, which could be said to be two sub-branches of environmental economics concerned with resource conservation in production, and the value of biodiversity to humans, respectively. The theory of natural capitalism (Hawken, Lovins, Lovins) goes further than traditional environmental economics by envisioning a world where natural services are considered on par with physical capital.

The more radical Green economists reject neoclassical economics in favour of a new political economy beyond capitalism or communism that gives a greater emphasis to the interaction of the human economy and the natural environment, acknowledging that “economy is three-fifths of ecology” – Mike Nickerson.

These more radical approaches would imply changes to money supply and likely also a bioregional democracy so that political, economic, and ecological “environmental limits” were all aligned, and not subject to the arbitrage normally possible under capitalism.

An emerging sub-field of environmental economics studies its intersection with development economics. Dubbed “envirodevonomics” by Michael Greenstone and B. Kelsey Jack in their paper “Envirodevonomics: A Research Agenda for a Young Field,” the sub-field is primarily interested in studying “why environmental quality so poor in developing countries.” A strategy for better understanding this correlation between a country’s GDP and its environmental quality involves analyzing how many of the central concepts of environmental economics, including market failures, externalities, and willingness to pay, may be complicated by the particular problems facing developing countries, such as political issues, lack of infrastructure, or inadequate financing tools, among many others.

Professional bodies

The main academic and professional organizations for the discipline of Environmental Economics are the Association of Environmental and Resource Economists (AERE) and the European Association for Environmental and Resource Economics (EAERE). The main academic and professional organization for the discipline of Ecological Economics is the International Society for Ecological Economics (ISEE). The main organization for Green Economics is the Green Economics Institute.

Source from Wikipedia