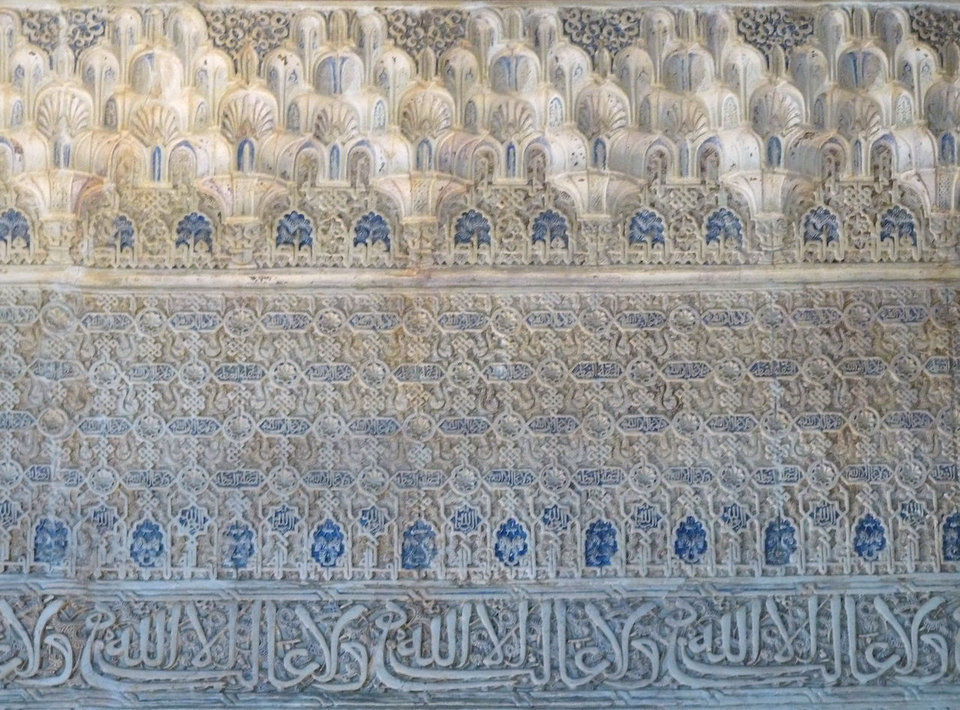

Yeseria is a technique of carving plaster used by the Spanish Moors like also by the post-Reconsquista’s Mudéjar architecture. Plaster was often carved into geometric and Islamic-influenced motifs. The Alhambra and the Córdoba Synagogue have many fine examples of yeseria.

History

It is assumed that plaster was introduced in the Iberian peninsula by Muslims, from the East, probably from Iran. Its use was abundant during Islamic domination, continuing during the period of the taifes kingdom. From here it spread to the Christian territories.

These plasterwork works are found in Christian churches, in synagogues in palaces and houses of main people. An important example of civil works is given to the Alcázar de Segovia whose work is documented in terms of authors and dates of execution. His study has provided important data in this regard. The Hall of the Throne or the Soli is signed and dated by Xadel Alcalde.

Some of the Mudejar palaces became convents and this fact gave rise to its conservation through the centuries; In addition, by doing some necessary works for its transformation it was necessary to call the same creators, thus constantly their names in the archives of the convents. In Castilla y León there is a clear example of the documents of the works of the Astudillo monastery in which the Brahmi algepser is named, who shortly after returns to appear in the works of the Consolation monastery (Calabazanos), where he performs some arches and a burial urn. In addition to other names of plaster casters, they are also known by means of documentary or by the own stamped signature when finishing their work.

The art of plasterwork extends until the sixteenth century in the Renaissance. In Castile and León, the work of the artists Corral de Villalpando, highly praised Algeciras masters, triumphs in this century. The iconographic motifs carried out by these artists have a great influence on carpentry works of the time devoted to roofs and choirs.

Techniques

For the execution of this work different techniques were used. The mold was used especially for the repeated friezes or for the inscriptions in the tombs or the works made in the pulpits. The subject was first drawn with an incision and elaborating the size. Emptying was done and different levels worked up to achieve the vegetal subjects or calligraphy or flowers that could finally be painted or gilded. The finish was sometimes made with oils to make the waterproof work.

The use of plaster was not limited to decoration. Sometimes it was used for lands instead of paved and wood. The technique consisted of mixing the plaster with marble powder and cooking at a very high temperature, which resulted in a great hardness. Sometimes it was stained with mangrove (red iron oxide). Thus the pavements of the palace of Astudillo and those of some choirs of churches or convents were obtained.

Decoration

Decoration in the Mudejar plasterwork was always considered an important work. The plaster or algepser artists, following the teachings of their ancestors, brought a wide and rich ornamentation to the Mudejar world. The large surfaces, walls and facades, were covered in full extent with a horror vacui approach. The main themes were arabesque, an ornamentation with stylized and intertwined vegetable repetitive motifs; the Mozarabic, which became one of the richest decorations in the Islamic world that presents some hawthorns or bee nests molded in plaster, decorating the architecture in friezes, tubes, shells, etc.; Handwriting, so appreciated by Muslims; the sebka, a lattice of diamonds and lobed and mixtiline tracings.

Decorated spaces

The spaces that were decorated on the architecture were numerous but also many of the architectural elements were made directly in plasterwork such as columns, capitals, arches, pulpits, stairs, tombs, etc. Some whole buildings had Mudejar plaster decorations; You can count palaces, houses that were luxurious residences, funerary chapels, synagogues. The favorite spaces were the frames of the doors and upper part of the walls, the capitals, latticework, friezes.

Examples of buildings that are conserved

In Castile and Leon some palaces or part of them are conserved, that when being transformed later in convents they did not undergo almost modifications. This is the case of the palace of King Peter I, where there is still a community of nuns Clarisses. Platters that are preserved are from the 14th century. In León, on Calle de la Rua, there was a palace, whose remains of plasterwork are stored in the National Archaeological Museum and in the Museum of León. In Segovia its Alcázar keeps whole rooms, whose walls are decorated with plasterwork, some frieze doors and strength. Also in Segovia had his Mudejar palace king Enrique III, founded in 1455, converted into a convent of Clarisses.

In Toledo there are interesting examples of plasterwork not only in its two well-known synagogues, that of Traffic and that of Santa Maria la Blanca, but in what were luxurious palaces such as the Casa de Mesa that is the seat of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts and Historical Sciences of Toledo, the Workshop of the Moor, palace of century XIV, turned into museum of art and crafts. The Palace of the Infantry of Guadalajara retains the 15th Century Linares Hall with vaults lined with Mozarabic only comparable to those of Alhambra in Granada.

In Andalusia, apart from the Alcázar, there are houses that were splendid residences such as the Casa de Pilatos or the Casa de las Dueñas, named the Palacio de las Dueñas in Seville.

Source From Wikipedia