Space-based solar power (SBSP) is the concept of collecting solar power in outer space and distributing it to Earth. Potential advantages of collecting solar energy in space include a higher collection rate and a longer collection period due to the lack of a diffusing atmosphere, and the possibility of placing a solar collector in an orbiting location where there is no night. A considerable fraction of incoming solar energy (55–60%) is lost on its way through the Earth’s atmosphere by the effects of reflection and absorption. Space-based solar power systems convert sunlight to microwaves outside the atmosphere, avoiding these losses and the downtime due to the Earth’s rotation, but at great cost due to the expense of launching material into orbit. SBSP is considered a form of sustainable or green energy, renewable energy, and is occasionally considered among climate engineering proposals. It is attractive to those seeking large-scale solutions to anthropogenic climate change or fossil fuel depletion (such as peak oil).

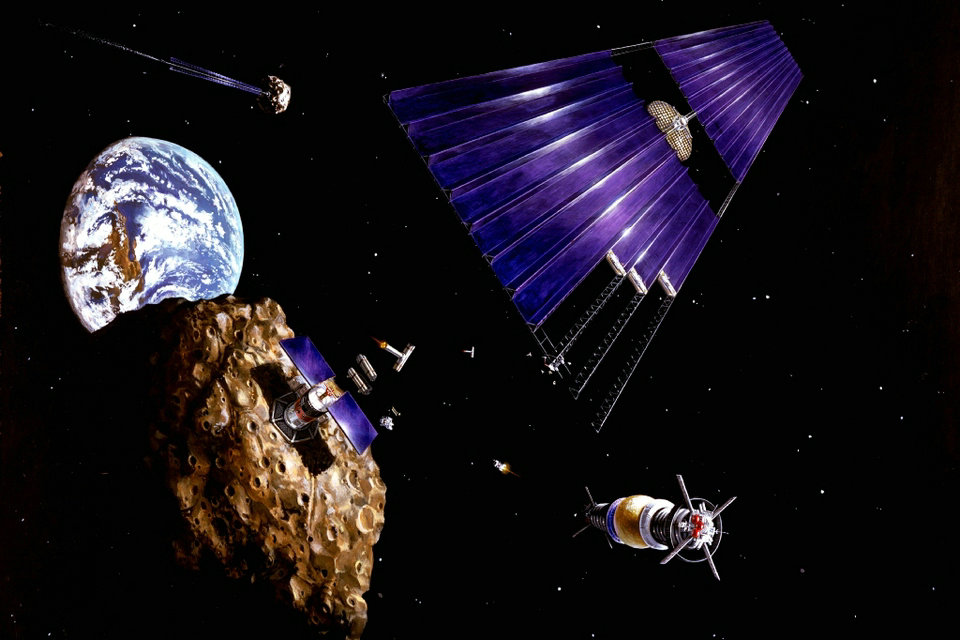

Various SBSP proposals have been researched since the early 1970s, but none are economically viable with present-day space launch infrastructure. A modest Gigawatt-range microwave system, comparable to a large commercial power plant, would require launching some 80,000 tons of material to orbit, making the cost of energy from such a system vastly more expensive than even present-day renewable energy. Some technologists speculate that this may change in the distant future if an off-world industrial base were to be developed that could manufacture solar power satellites out of asteroids or lunar material, or if radical new space launch technologies other than rocketry should become available in the future.

Besides the cost of implementing such a system, SBSP also introduces several technological hurdles, including the problem of transmitting energy from orbit to Earth’s surface for use. Since wires extending from Earth’s surface to an orbiting satellite are neither practical nor feasible with current technology, SBSP designs generally include the use of some manner of wireless power transmission with its concomitant conversion inefficiencies, as well as land use concerns for the necessary antenna stations to receive the energy at Earth’s surface. The collecting satellite would convert solar energy into electrical energy on board, powering a microwave transmitter or laser emitter, and transmit this energy to a collector (or microwave rectenna) on Earth’s surface. Contrary to appearances of SBSP in popular novels and video games, most designs propose beam energy densities that are not harmful if human beings were to be inadvertently exposed, such as if a transmitting satellite’s beam were to wander off-course. But the vast size of the receiving antennas that would be necessary would still require large blocks of land near the end users to be procured and dedicated to this purpose. The service life of space-based collectors in the face of challenges from long-term exposure to the space environment, including degradation from radiation and micrometeoroid damage, could also become a concern for SBSP.

SBSP is being actively pursued by Japan, China, and Russia. In 2008 Japan passed its Basic Space Law which established Space Solar Power as a national goal and JAXA has a roadmap to commercial SBSP. In 2015 the China Academy for Space Technology (CAST) briefed their roadmap at the International Space Development Conference (ISDC) where they showcased their road map to a 1 GW commercial system in 2050 and unveiled a video and description of their design.

Challenges

Potential

The SBSP concept is attractive because space has several major advantages over the Earth’s surface for the collection of solar power:

It is always solar noon in space and full sun.

Collecting surfaces could receive much more intense sunlight, owing to the lack of obstructions such as atmospheric gasses, clouds, dust and other weather events. Consequently, the intensity in orbit is approximately 144% of the maximum attainable intensity on Earth’s surface.

A satellite could be illuminated over 99% of the time, and be in Earth’s shadow a maximum of only 72 minutes per night at the spring and fall equinoxes at local midnight. Orbiting satellites can be exposed to a consistently high degree of solar radiation, generally for 24 hours per day, whereas earth surface solar panels currently collect power for an average of 29% of the day.

Power could be relatively quickly redirected directly to areas that need it most. A collecting satellite could possibly direct power on demand to different surface locations based on geographical baseload or peak load power needs. Typical contracts would be for baseload, continuous power, since peaking power is ephemeral.

Elimination of plant and wildlife interference.

With very large scale implementations, especially at lower altitudes, it potentially can reduce incoming solar radiation reaching earth’s surface. This would be desirable for counteracting the effects of global warming.

Drawbacks

The SBSP concept also has a number of problems:

The large cost of launching a satellite into space

The thinned-array curse preventing efficient transmission of power from space to the Earth’s surface

Inaccessibility: Maintenance of an earth-based solar panel is relatively simple, but construction and maintenance on a solar panel in space would typically be done telerobotically. In addition to cost, astronauts working in GEO (geosynchronous Earth orbit) are exposed to unacceptably high radiation dangers and risk and cost about one thousand times more than the same task done telerobotically.

The space environment is hostile; panels suffer about 8 times the degradation they would on Earth (except at orbits that are protected by the magnetosphere).

Space debris is a major hazard to large objects in space, and all large structures such as SBSP systems have been mentioned as potential sources of orbital debris.

The broadcast frequency of the microwave downlink (if used) would require isolating the SBSP systems away from other satellites. GEO space is already well used and it is considered unlikely the ITU would allow an SPS to be launched.[irrelevant citation]

The large size and corresponding cost of the receiving station on the ground.

Energy losses during several phases of conversion from photons to electrons to photons back to electrons.

Design

Space-based solar power essentially consists of three elements:

collecting solar energy in space with reflectors or inflatable mirrors onto solar cells

wireless power transmission to Earth via microwave or laser

receiving power on Earth via a rectenna, a microwave antenna

The space-based portion will not need to support itself against gravity (other than relatively weak tidal stresses). It needs no protection from terrestrial wind or weather, but will have to cope with space hazards such as micrometeors and solar flares. Two basic methods of conversion have been studied: photovoltaic (PV) and solar dynamic (SD). Most analyses of SBSP have focused on photovoltaic conversion using solar cells that directly convert sunlight into electricity. Solar dynamic uses mirrors to concentrate light on a boiler. The use of solar dynamic could reduce mass per watt. Wireless power transmission was proposed early on as a means to transfer energy from collection to the Earth’s surface, using either microwave or laser radiation at a variety of frequencies.

Microwave power transmission

William C. Brown demonstrated in 1964, during Walter Cronkite’s CBS News program, a microwave-powered model helicopter that received all the power it needed for flight from a microwave beam. Between 1969 and 1975, Bill Brown was technical director of a JPL Raytheon program that beamed 30 kW of power over a distance of 1 mile (1.6 km) at 84% efficiency.

Microwave power transmission of tens of kilowatts has been well proven by existing tests at Goldstone in California (1975) and Grand Bassin on Reunion Island (1997).

More recently, microwave power transmission has been demonstrated, in conjunction with solar energy capture, between a mountain top in Maui and the island of Hawaii (92 miles away), by a team under John C. Mankins. Technological challenges in terms of array layout, single radiation element design, and overall efficiency, as well as the associated theoretical limits are presently a subject of research, as it is demonstrated by the Special Session on “Analysis of Electromagnetic Wireless Systems for Solar Power Transmission” to be held in the 2010 IEEE Symposium on Antennas and Propagation. In 2013, a useful overview was published, covering technologies and issues associated with microwave power transmission from space to ground. It includes an introduction to SPS, current research and future prospects. Moreover, a review of current methodologies and technologies for the design of antenna arrays for microwave power transmission appeared in the Proceedings of the IEEE

Laser power beaming

Laser power beaming was envisioned by some at NASA as a stepping stone to further industrialization of space. In the 1980s, researchers at NASA worked on the potential use of lasers for space-to-space power beaming, focusing primarily on the development of a solar-powered laser. In 1989 it was suggested that power could also be usefully beamed by laser from Earth to space. In 1991 the SELENE project (SpacE Laser ENErgy) had begun, which included the study of laser power beaming for supplying power to a lunar base. The SELENE program was a two-year research effort, but the cost of taking the concept to operational status was too high, and the official project ended in 1993 before reaching a space-based demonstration.

In 1988 the use of an Earth-based laser to power an electric thruster for space propulsion was proposed by Grant Logan, with technical details worked out in 1989. He proposed using diamond solar cells operating at 600 degrees to convert ultraviolet laser light.

Orbital location

The main advantage of locating a space power station in geostationary orbit is that the antenna geometry stays constant, and so keeping the antennas lined up is simpler. Another advantage is that nearly continuous power transmission is immediately available as soon as the first space power station is placed in orbit; other space-based power stations have much longer start-up times before they are producing nearly continuous power. A collection of LEO (Low Earth Orbit) space power stations has been proposed as a precursor to GEO (Geostationary Orbit) space-based solar power.

Earth-based receiver

The Earth-based rectenna would likely consist of many short dipole antennas connected via diodes. Microwave broadcasts from the satellite would be received in the dipoles with about 85% efficiency. With a conventional microwave antenna, the reception efficiency is better, but its cost and complexity are also considerably greater. Rectennas would likely be several kilometers across.

In space applications

A laser SBSP could also power a base or vehicles on the surface of the Moon or Mars, saving on mass costs to land the power source. A spacecraft or another satellite could also be powered by the same means. In a 2012 report presented to NASA on Space Solar Power, the author mentions another potential use for the technology behind Space Solar Power could be for Solar Electric Propulsion Systems that could be used for interplanetary human exploration missions.

Launch costs

One problem for the SBSP concept is the cost of space launches and the amount of material that would need to be launched.

Much of the material launched need not be delivered to its eventual orbit immediately, which raises the possibility that high efficiency (but slower) engines could move SPS material from LEO to GEO at an acceptable cost. Examples include ion thrusters or nuclear propulsion. Power beaming from geostationary orbit by microwaves carries the difficulty that the required ‘optical aperture’ sizes are very large. For example, the 1978 NASA SPS study required a 1-km diameter transmitting antenna, and a 10 km diameter receiving rectenna, for a microwave beam at 2.45 GHz. These sizes can be somewhat decreased by using shorter wavelengths, although they have increased atmospheric absorption and even potential beam blockage by rain or water droplets. Because of the thinned array curse, it is not possible to make a narrower beam by combining the beams of several smaller satellites. The large size of the transmitting and receiving antennas means that the minimum practical power level for an SPS will necessarily be high; small SPS systems will be possible, but uneconomic.

To give an idea of the scale of the problem, assuming a solar panel mass of 20 kg per kilowatt (without considering the mass of the supporting structure, antenna, or any significant mass reduction of any focusing mirrors) a 4 GW power station would weigh about 80,000 metric tons, all of which would, in current circumstances, be launched from the Earth. Very lightweight designs could likely achieve 1 kg/kW, meaning 4,000 metric tons for the solar panels for the same 4 GW capacity station. This would be the equivalent of between 40 and 150 heavy-lift launch vehicle (HLLV) launches to send the material to low earth orbit, where it would likely be converted into subassembly solar arrays, which then could use high-efficiency ion-engine style rockets to (slowly) reach GEO (Geostationary orbit). With an estimated serial launch cost for shuttle-based HLLVs of $500 million to $800 million, and launch costs for alternative HLLVs at $78 million, total launch costs would range between $11 billion (low cost HLLV, low weight panels) and $320 billion (‘expensive’ HLLV, heavier panels). To these costs must be added the environmental impact of heavy space launch missions, if such costs are to be used in comparison to earth-based energy production. For comparison, the direct cost of a new coal or nuclear power plant ranges from $3 billion to $6 billion per GW (not including the full cost to the environment from CO2 emissions or storage of spent nuclear fuel, respectively); another example is the Apollo missions to the Moon cost a grand total of $24 billion (1970s dollars), taking inflation into account, would cost $140 billion today, more expensive than the construction of the International Space Station.

Building from space

From lunar materials launched in orbit

Gerard O’Neill, noting the problem of high launch costs in the early 1970s, proposed building the SPS’s in orbit with materials from the Moon. Launch costs from the Moon are potentially much lower than from Earth, due to the lower gravity and lack of atmospheric drag. This 1970s proposal assumed the then-advertised future launch costing of NASA’s space shuttle. This approach would require substantial up front capital investment to establish mass drivers on the Moon. Nevertheless, on 30 April 1979, the Final Report (“Lunar Resources Utilization for Space Construction”) by General Dynamics’ Convair Division, under NASA contract NAS9-15560, concluded that use of lunar resources would be cheaper than Earth-based materials for a system of as few as thirty Solar Power Satellites of 10GW capacity each.

In 1980, when it became obvious NASA’s launch cost estimates for the space shuttle were grossly optimistic, O’Neill et al. published another route to manufacturing using lunar materials with much lower startup costs. This 1980s SPS concept relied less on human presence in space and more on partially self-replicating systems on the lunar surface under remote control of workers stationed on Earth. The high net energy gain of this proposal derives from the Moon’s much shallower gravitational well.

Having a relatively cheap per pound source of raw materials from space would lessen the concern for low mass designs and result in a different sort of SPS being built. The low cost per pound of lunar materials in O’Neill’s vision would be supported by using lunar material to manufacture more facilities in orbit than just solar power satellites. Advanced techniques for launching from the Moon may reduce the cost of building a solar power satellite from lunar materials. Some proposed techniques include the lunar mass driver and the lunar space elevator, first described by Jerome Pearson. It would require establishing silicon mining and solar cell manufacturing facilities on the Moon.

On the Moon

Physicist Dr David Criswell suggests the Moon is the optimum location for solar power stations, and promotes lunar-based solar power. The main advantage he envisions is construction largely from locally available lunar materials, using in-situ resource utilization, with a teleoperated mobile factory and crane to assemble the microwave reflectors, and rovers to assemble and pave solar cells, which would significantly reduce launch costs compared to SBSP designs. Power relay satellites orbiting around earth and the Moon reflecting the microwave beam are also part of the project. A demo project of 1 GW starts at $50 billion. The Shimizu Corporation use combination of lasers and microwave for the Luna Ring concept, along with power relay satellites.

From an asteroid

Asteroid mining has also been seriously considered. A NASA design study evaluated a 10,000 ton mining vehicle (to be assembled in orbit) that would return a 500,000 ton asteroid fragment to geostationary orbit. Only about 3,000 tons of the mining ship would be traditional aerospace-grade payload. The rest would be reaction mass for the mass-driver engine, which could be arranged to be the spent rocket stages used to launch the payload. Assuming that 100% of the returned asteroid was useful, and that the asteroid miner itself couldn’t be reused, that represents nearly a 95% reduction in launch costs. However, the true merits of such a method would depend on a thorough mineral survey of the candidate asteroids; thus far, we have only estimates of their composition. One proposal is to capture the asteroid Apophis into earth orbit and convert it into 150 solar power satellites of 5 GW each or the larger asteroid 1999 AN10 which is 50x the size of Apophis and large enough to build 7,500 5-Gigawatt Solar Power Satellites

Non-typical configurations and architectural considerations

The typical reference system-of-systems involves a significant number (several thousand multi-gigawatt systems to service all or a significant portion of Earth’s energy requirements) of individual satellites in GEO. The typical reference design for the individual satellite is in the 1-10 GW range and usually involves planar or concentrated solar photovoltaics (PV) as the energy collector / conversion. The most typical transmission designs are in the 1–10 GHz (2.45 or 5.8 GHz) RF band where there are minimum losses in the atmosphere. Materials for the satellites are sourced from, and manufactured on Earth and expected to be transported to LEO via re-usable rocket launch, and transported between LEO and GEO via chemical or electrical propulsion. In summary, the architecture choices are:

Location = GEO

Energy Collection = PV

Satellite = Monolithic Structure

Transmission = RF

Materials & Manufacturing = Earth

Installation = RLVs to LEO, Chemical to GEO

There are several interesting design variants from the reference system:

Alternate energy collection location: While GEO is most typical because of its advantages of nearness to Earth, simplified pointing and tracking, very small time in occultation, and scalability to meet all global demand several times over, other locations have been proposed:

Sun Earth L1: Robert Kennedy III, Ken Roy & David Fields have proposed a variant of the L1 sunshade called “Dyson Dots” where a multi-terawatt primary collector would beam energy back to a series of LEO sun-synchronous receiver satellites. The much farther distance to Earth requires a correspondingly larger transmission aperture.

Lunar Surface: Dr. David Criswell has proposed using the Lunar surface itself as the collection medium, beaming power to the ground via a series of microwave reflectors in Earth Orbit. The chief advantage of this approach would be the ability to manufacture the solar collectors in-situ without the energy cost and complexity of launch. Disadvantages include the much longer distance, requiring larger transmission systems, the required “overbuild” to deal with the lunar night, and the difficulty of sufficient manufacturing and pointing of reflector satellites.

MEO: MEO systems have been proposed for in-space utilities and beam-power propulsion infrastructures. For example, see Royce Jones’ paper.

Highly Elliptical Orbits: Molniya, Tundra, or Quazi Zenith orbits have been proposed as early locations for niche markets, requiring less energy to access and providing good persistence.

Sun-Sync LEO: In this near Polar Orbit, the satellites precess at a rate that allows them to always face the Sun as they rotate around Earth. This is an easy to access orbit requiring far less energy, and its proximity to Earth requires smaller (and therefore less massive) transmitting apertures. However disadvantages to this approach include having to constantly shift receiving stations, or storing energy for a burst transmission. This orbit is already crowded and has significant space debris.

Equatorial LEO: Japan’s SPS 2000 proposed an early demonstrator in equatorial LEO in which multiple equatorial participating nations could receive some power.

Earth’s Surface: Dr. Narayan Komerath has proposed a space power grid where excess energy from an existing grid or power plant on one side of the planet can be passed up to orbit, across to another satellite and down to receivers.

Energy Collection: The most typical designs for Solar Power Satellites include photovoltaics. These may be planar (and usually passively cooled), concentrated (and perhaps actively cooled). However, there are multiple interesting variants.

Solar Thermal: Proponents of Solar Thermal have proposed using concentrated heating to cause a state change in a fluid to extract energy via rotating machinery followed by cooling in radiators. Advantages of this method might include overall system mass (disputed), non-degradation due to solar-wind damage, and radiation tolerance. One recent thermal solar power satellite design by Keith Henson has been visualized here.

Solar Pumped Laser: Japan has pursued a solar-pumped laser, where sunlight directly excites the lasing medium used to create the coherent beam to Earth.

Fusion Decay: This version of a power-satellite is not “solar”. Rather, the vacuum of space is seen as a “feature not a bug” for traditional fusion. Per Dr. Paul Werbos, after fusion even neutral particles decay to charged particles which in a sufficiently large volume would allow direct conversion to current.[citation needed]

Solar Wind Loop: Also called a Dyson–Harrop satellite. Here the satellite makes use not of the photons from the Sun but rather the charged particles in the solar wind which via electro-magnetic coupling generate a current in a large loop.

Direct Mirrors: Early concepts for direct mirror re-direction of light to planet Earth suffered from the problem that rays coming from the sun are not parallel but are expanding from a disk and so the size of the spot on the Earth is quite large. Dr. Lewis Fraas has explored an array of parabolic mirrors to augment existing solar arrays.

Alternate Satellite Architecture: The typical satellite is a monolithic structure composed of a structural truss, one or more collectors, one or more transmitters, and occasionally primary and secondary reflectors. The entire structure may be gravity gradient stabilized. Alternative designs include:

Swarms of Smaller Satellites: Some designs propose swarms of free-flying smaller satellites. This is the case with several laser designs, and appears to be the case with CALTECH’s Flying Carpets. For RF designs, an engineering constraint is the sparse array problem.

Free Floating Components: Solaren has proposed an alternative to the monolithic structure where the primary reflector and transmission reflector are free-flying.

Spin Stabilization: NASA explored a spin-stabilized thin film concept.

Photonic Laser Thruster (PLT) stabilized structure: Dr. Young Bae has proposed that photon pressure may substitute for compressive members in large structures.

Transmission: The most typical design for energy transmission is via an RF antenna at below 10 GHz to a rectenna on the ground. Controversy exists between the benefits of Klystrons, Gyrotrons, Magnetrons and solid state. Alternate transmission approaches include:

Laser: Lasers offer the advantage of much lower cost and mass to first power, however there is controversy regarding benefits of efficiency. Lasers allow for much smaller transmitting and receiving apertures. However, a highly concentrated beam has eye-safety, fire safety, and weaponization concerns. Proponents believe they have answers to all these concerns. A laser-based approach must also find alternate ways of coping with precipitation.

Atmospheric Waveguide: Some have proposed it may be possible to use a short pulse laser to create an atmospheric waveguide through which concentrated microwaves could flow.

Scalar: Some have even speculated it may be possible to transmit power through scalar waves.

Nuclear synthesis: Particle accelerators based in the inner solar system (whether in orbit or on a planet such as Mercury) could use solar energy to synthesize nuclear fuel from naturally-occurring materials. While this would be highly inefficient using current technology (in terms of the amount of energy needed to manufacture the fuel compared to the amount of energy contained in the fuel) and would raise obvious nuclear safety issues, the basic technology upon which such an approach would rely on has been in use for decades, making this possibly the most reliable means of sending energy especially over very long distances – in particular, from the inner solar system to the outer solar system.

Materials and Manufacturing: Typical designs make use of the developed industrial manufacturing system extant on Earth, and use Earth based materials both for the satellite and propellant. Variants include:

Lunar Materials: Designs exist for Solar Power Satellites that source >99% of materials from lunar regolith with very small inputs of “vitamins” from other locations. Using materials from the Moon is attractive because launch from the Moon is in theory far less complicated than from Earth. There is no atmosphere, and so components do not need to be packed tightly in an aeroshell and survive vibration, pressure and temperature loads. Launch may be via a magnetic mass driver and the requirement to use propellant for launch entirely. Launch from the Moon the GEO also requires far less energy than from Earth’s much deeper gravity well. Building all the solar power satellites to fully supply all the required energy for the entire planet requires less than one millionth of the mass of the Moon.

Self-Replication on the Moon: NASA explored a self-replicating factory on the Moon in 1980. More recently, Justin Lewis-Webber proposed a method of speciated manufacture of core elements based upon John Mankins SPS-Alpha design.

Asteroidal Materials: Some asteroids are thought to have even lower Delta-V to recover materials than the Moon, and some particular materials of interest such as metals may be more concentrated or easier to access.

In-Space/In-Situ Manufacturing: With the advent of in-space additive manufacturing, concepts such as SpiderFab might allow mass launch of raw materials for local extrusion.

Counter arguments

Safety

The use of microwave transmission of power has been the most controversial issue in considering any SPS design. At the Earth’s surface, a suggested microwave beam would have a maximum intensity at its center, of 23 mW/cm2 (less than 1/4 the solar irradiation constant), and an intensity of less than 1 mW/cm2 outside the rectenna fenceline (the receiver’s perimeter). These compare with current United States Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSHA) workplace exposure limits for microwaves, which are 10 mW/cm2, – the limit itself being expressed in voluntary terms and ruled unenforceable for Federal OSHA enforcement purposes. A beam of this intensity is therefore at its center, of a similar magnitude to current safe workplace levels, even for long term or indefinite exposure. Outside the receiver, it is far less than the OSHA long-term levels Over 95% of the beam energy will fall on the rectenna. The remaining microwave energy will be absorbed and dispersed well within standards currently imposed upon microwave emissions around the world. It is important for system efficiency that as much of the microwave radiation as possible be focused on the rectenna. Outside the rectenna, microwave intensities rapidly decrease, so nearby towns or other human activity should be completely unaffected.

Exposure to the beam is able to be minimized in other ways. On the ground, physical access is controllable (e.g., via fencing), and typical aircraft flying through the beam provide passengers with a protective metal shell (i.e., a Faraday Cage), which will intercept the microwaves. Other aircraft (balloons, ultralight, etc.) can avoid exposure by observing airflight control spaces, as is currently done for military and other controlled airspace. The microwave beam intensity at ground level in the center of the beam would be designed and physically built into the system; simply, the transmitter would be too far away and too small to be able to increase the intensity to unsafe levels, even in principle.

In addition, a design constraint is that the microwave beam must not be so intense as to injure wildlife, particularly birds. Experiments with deliberate microwave irradiation at reasonable levels have failed to show negative effects even over multiple generations. Suggestions have been made to locate rectennas offshore, but this presents serious problems, including corrosion, mechanical stresses, and biological contamination.

A commonly proposed approach to ensuring fail-safe beam targeting is to use a retrodirective phased array antenna/rectenna. A “pilot” microwave beam emitted from the center of the rectenna on the ground establishes a phase front at the transmitting antenna. There, circuits in each of the antenna’s subarrays compare the pilot beam’s phase front with an internal clock phase to control the phase of the outgoing signal. This forces the transmitted beam to be centered precisely on the rectenna and to have a high degree of phase uniformity; if the pilot beam is lost for any reason (if the transmitting antenna is turned away from the rectenna, for example) the phase control value fails and the microwave power beam is automatically defocused. Such a system would be physically incapable of focusing its power beam anywhere that did not have a pilot beam transmitter. The long-term effects of beaming power through the ionosphere in the form of microwaves has yet to be studied, but nothing has been suggested which might lead to any significant effect.

Source from Wikipedia