Nouvelle Tendance is a nonaligned modernist art movement, emerged in the early 1960s in the former Yugoslavia, a nonaligned country. It represented a new sensibility, rejecting both Abstract Expressionism and socialist realism in an attempt to formulate an art adequate to the age of advanced mass production.

the development of New Tendencies as a major international art movement in the context of social, political, and technological history. Doing so, he traces concurrent paradigm shifts: the change from Fordism (the political economy of mass production and consumption) to the information society, and the change from postwar modernism to dematerialized postmodern art practices.

New Tendencies, rather than opposing the forces of technology as most artists and intellectuals of the time did, imagined the rapid advance of technology to be a springboard into a future beyond alienation and oppression. Works by New Tendencies cast the viewer as coproducer, abolishing the idea of artist as creative genius and replacing it with the notion of the visual researcher. In 1968 and 1969, the group actively turned to the computer as a medium of visual research, anticipating new media and digital art.

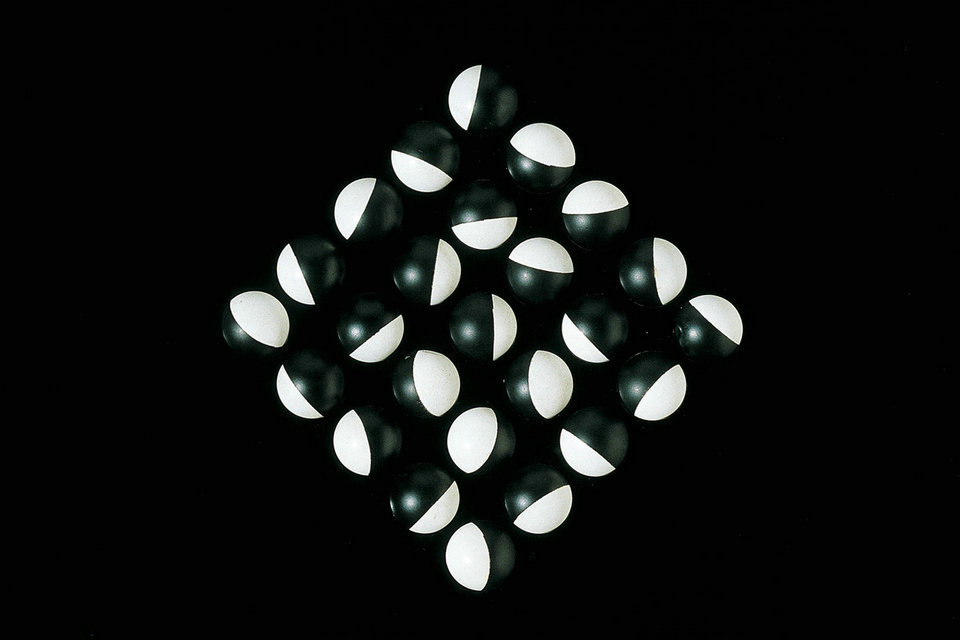

The Nouvelle Tendance was more accurately a reflection of common approaches used by artists in a variety of simultaneous movements worldwide, such as Concrete art, Kinetic art, and Op Art. The main consideration of the movement has been described as the “problem of movement as conveyed through repetition”. The “sensation of displeasure” is provoked in some Nouvelle Tendance works, to “stimulate a more active field of vision” and interest the spectator in an “auto-creative process”.

Artist group:

The “theoretician” of the group was Serbian art critic Marko Mestrovich. The other original founders of Nouvelle Tendance were Brazilian painter Almir Mavignier, and Bozo Bek, the Croatian director of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Zagreb.

Medosch discusses modernization in then-Yugoslavia and other nations on the periphery; looks in detail at New Tendencies’ five major exhibitions in Zagreb (the capital of Croatia); and considers such topics as the group’s relation to science, the changing relationship of manual and intellectual labor, New Tendencies in the international art market, their engagement with computer art, and the group’s eventual eclipse by other “new art practices” including conceptualism, land art, and arte povera. Numerous illustrations document New Tendencies’ works and exhibitions.

Distinct self-identified groups of artists who became associated with Nouvelle Tendance included GRAV, Gruppo T, Gruppo N, and Zero. The movement attracted artists from France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and Spain. International artists participated in a series of exhibits at European galleries.

Nouvelle tendance artists recognized themselves as subjects of a common sentiment, as more orientated towards design and architecture, sociology or psychology than to individual artistic poetics. At hand was a kind of spontaneous germination that envisioned young people from disparate areas of study and various professions working together. From that point on they formed groups centered upon collective working. Many were completely new to the field of art and only a small minority came from art academies.

Nouvelle tendance artists worked on optical problems, perception, virtual images, the intrinsic dynamism of the work, the intervention of the spectator, on light and space, on seriality, new materials and on an unseen presentation of what was known, with mathematics and exact forms as a base. All of this was conducted with a new spirit, with a rationality and logic that promoted new operative modes, different expressive possibilities and all those elaborated phenomena, ideologies and psychologies relative to the problems of the visual and the optical. These were needs that addressed the human conscious, yet with a research approach closer to science. Nouvelle tendance wanted to give art a scientific meaning and consequently a social dimension. This was an art based on objectivity, free from any literal interpretation, art as a proposition and resolution of plastic problems that were always verifiable. This was an art that amplified the field of knowledge, maintaining a strong didactic component.

This group should not be confused with an early 20th century circle of Paris-based artists who operated briefly under the name “Tendances nouvelles” and held an exhibition in 1904; founding members included Alice Dannenberg and Martha Stettler.

Exhibition

Commencing with the 1961 exhibition of concrete and constructive art Nove tendencije in Zagreb, the New Tendencies developed into a dynamic movement dedicated to visual research. Around the mid-1960s, the New Tendencies triggered an international Op-Art-boom, which was endorsed by participation in an exhibition entitled The Responsive Eye, at the New York MoMA, in 1965. However, success brought the New Tendencies no closer to its aims: the assertion of ‘art as research’ and the establishment of new forms of distribution beyond the art market, which should be accessible to everyman.

The organizers of the New Tendencies decided to bring their strategy up-to-date and, in the summer of 1968, initiated in the context of the fourth exhibition, Tendencije 4, the program Computer and Visual Research. In 1968 the movement decided to incorporate into its program the computer as a medium of artistic work so as to thereby assert its avantgarde claim and to contribute to the definition of a technology which, as one quite rightly presumed, would define the future of civilization.

Until 1973 the supporting institution of the New Tendencies, the former Gallery of Contemporary Art Zagreb – today the Museum of Contemporary Art – had dedicated itself to artistic research by computer with a series of international exhibitions and symposia. At the peak of the Cold War artists and scientists throughout the world presented their work in Zagreb. The New Tendencies thus established a unique platform for the exchange of ideas and experiences from the area of art, the natural sciences and engineering. With the multi-lingual journal Bit International Zagreb became a point of initiation for aesthetics and media-theoretical thought.

The organizers of NT initially sought to consciously accompany and form the historical transition in which the computer was perceived as medium of artistic creation. They set computer generated works in relation to Constructive and Kinetic art (1968/69) and to Conceptual art (1973). The arts of the electronic media were not considered as an isolated phenomenon but rather incorporated into the history and discourse of fine-and performing arts.