The Museum of natural history is a scientific institution with natural history collections that include current and historical records of animals, plants, fungi, ecosystems, geology, paleontology, climatology, and more. The primary role of a natural history museum is to provide the scientific community with current and historical specimens for their research, which is to improve our understanding of the natural world. Some museums have public exhibits to share the beauty and wonder of the natural world with the public; these are referred to as ‘public museums’. Some museums feature non-natural history collections in addition to their primary collections, such as ones related to history, art, and science.

The Natural History Museum is a world-class visitor attraction and leading science research centre. We use our unique collections and unrivaled expertise to tackle the biggest challenges facing the world today. Explore a story of natural history discovery in an interactive experience, Making Natural History, voiced by Museum researchers and curators. Dive into the museum’s 80 million specimens with unique, new features: encounter a prehistoric marine reptile in virtual reality, take a tour of ten new exhibits tackling natural history themes, and take students on an expedition through the galleries to learn about adaptation in the natural world.

Renaissance cabinets of curiosities were private collections that typically included exotic specimens of natural history, sometimes faked, along with other types of object. The first natural history museum was possibly that of Swiss scholar Conrad Gessner, established in Zürich in the mid-16th century. The Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, established in Paris in 1635, was the first natural history museum to take the form that would be recognized as a natural history museum today. Early natural history museums offered limited accessibility, as they were generally private collections or holdings of scientific societies. The Ashmolean Museum, opened in 1683, was the first natural history museum to grant admission to the general public.

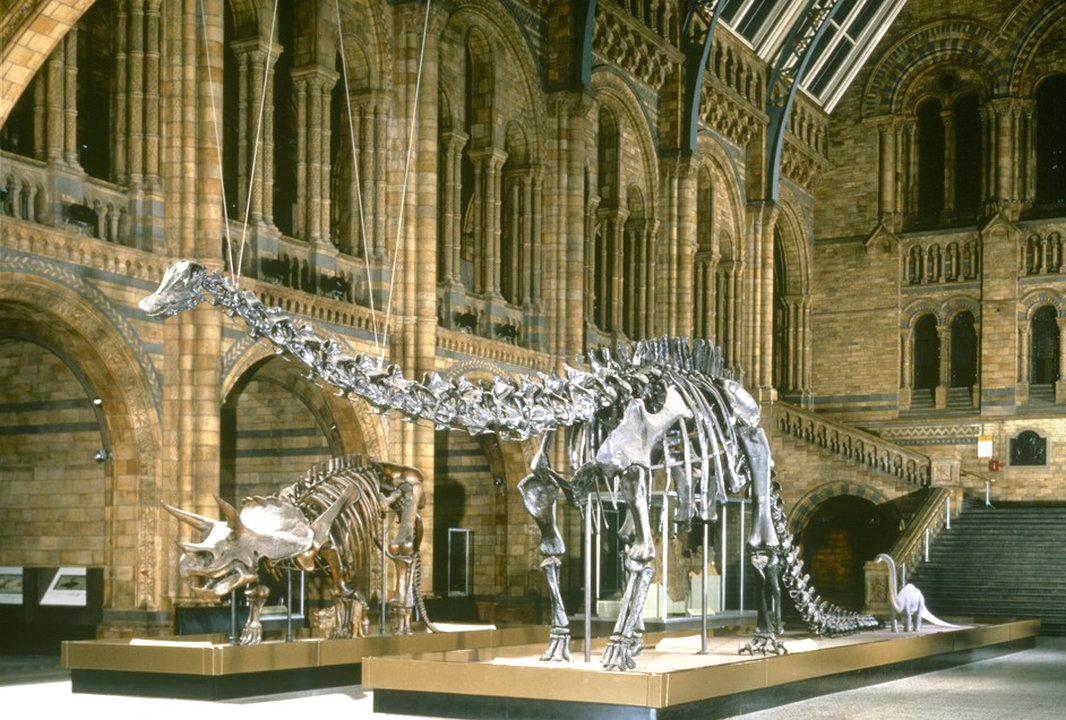

One of the most famous and certainly most prominent of the exhibits—nicknamed “Dippy”—is a 105-foot (32 m)-long replica of a Diplodocus carnegii skeleton situated within the central hall. After 112 years on display at the museum, the dinosaur replica was removed in early 2017 to be replaced by the actual skeleton of a young blue whale. Dippy will start a tour of British museums in 2018.

The blue whale skeleton that would replace Dippy is another iconic display in the museum. The display of the skeleton, some 25 m long and weighing 10 tons, was only made possible in 1934 with the building of the New Whale Hall (now the Large Mammals Hall). The whale had been in storage for 42 years since its stranding on sandbanks at the mouth of Wexford Harbour, Ireland in March 1891 after being injured by whalers.

The Darwin Centre is host to Archie, an eight-metre-long giant squid taken alive in a fishing net near the Falkland Islands in 2004. The squid is not on general display, but stored in the large tank room in the basement of the Phase 1 building. On arrival at the museum, the specimen was immediately frozen while preparations commenced for its permanent storage. Since few complete and reasonably fresh examples of the species exist, “wet storage” was chosen, leaving the squid undissected. A 9.45-metre acrylic tank was constructed (by the same team that provide tanks to Damien Hirst), and the body preserved using a mixture of formalin and saline solution.

The museum holds the remains and bones of the “River Thames whale”, a northern bottlenose whale that lost its way on 20 January 2006 and swam into the Thames. Although primarily used for research purposes, and held at the museum’s storage site at Wandsworth, the skeleton has been put on temporary public display.

Dinocochlea, one of the longer-standing mysteries of paleontology (originally thought to be a giant gastropod shell, then a coprolite and now a concretion of a worm’s tunnel), has been part of the collection since its discovery in 1921.

The museum keeps a wildlife garden on its west lawn, on which a potentially new species of insect resembling Arocatus roeselii was discovered in 2007.