The Hamzanama (Persian/Urdu: حمزه نامه Hamzenâme, Epic of Hamza) or Dastan-e-Amir Hamza (Persian/Urdu: داستان امیر حمزه Dâstâne Amir Hamze, Adventures of Amir Hamza) narrates the legendary exploits of Amir Hamza, an uncle of the Prophet Muhammad, though most of the stories are extremely fanciful, “a continuous series of romantic interludes, threatening events, narrow escapes, and violent acts”.

Most of the characters of the Hamzanama are fictitious. In the West the work is best known for the enormous illustrated manuscript commissioned by the Mughal Emperor Akbar in about 1562.

The Hamzanama contains 46 volumes and has approximately 48000 pages. It is said that Dastaan Ameer Hamza was written in the era of Mahmud of Ghazni.

The text augmented the story, as traditionally told in dastan performances. The dastan (storytelling tradition) about Amir Hamza persists far and wide up to Bengal and Arakan (Burma), as the Mughals controlled those territories.

Akbar’s manuscript

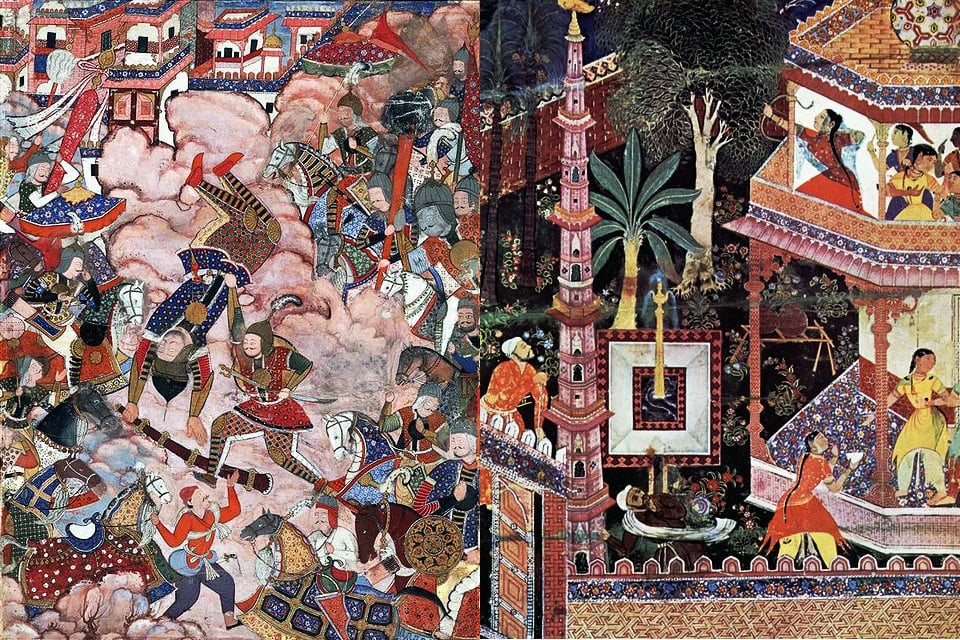

Though the first Mughal Emperor, Babur, described the Hamzanama as “one long far-fetched lie; opposed to sense and nature”, his grandson Akbar, who came to the throne at the age of fourteen, greatly enjoyed it. He commissioned his court workshop to create an illustrated manuscript of the Hamzanama early in his reign (he was by then about twenty), which was conceived on such an unusually large scale that it took fourteen years, from about 1562 to 1577, to complete. Apart from the text, it included 1400 full page Mughal miniatures of an unusually large size, nearly all painted on paper, which were then glued to a cloth backing. The work was bound in 14 volumes. After the early pages, where various layouts were experimented with, one side of most folios has a painting, about 69 cm x 54 cm (approx. 27 x 20 inches) in size, done in a fusion of Persian and Mughal styles. On the other side is the text in Persian in Nasta’liq script, arranged so that the text is opposite the matching picture in most openings of the book.

The size of the commission was completely unprecedented, and stretched even the huge imperial workshop. According to contemporary accounts, about thirty main artists were used, and over a hundred men worked on the various aspects of the book in all. According to Badauni and Shahnawaz Khan the work of preparing the illustrations was supervised initially by Mir Sayyid Ali and subsequently by Abdus Samad, the former possibly being replaced as head of the workshop because the pace of production was too slow. After seven years only four volumes were completed, but the new head was able to galvanize production and complete the ten volumes in another seven years, without any loss of quality. Indeed, “the later pages are the most exciting and innovative in the work”.

The colophon of this manuscript is still missing. None of the folios of this manuscript so far found is signed, though many have been attributed to different artists. Compared to Akbar’s Tutinama, a smaller commission begun and completed while the Hamzanama commission was in progress, the manuscript shows a much greater fusion of the styles of Indian and Persian miniatures. Though the elegance and finish may seem closer to Persian works, the compositional style and narrative drama owe more to Indian tradition. Between them, these two manuscripts are the key works in the formation of the Mughal miniature style.

Only a little over a hundred of the paintings survive. The largest group of 61 images is in the Museum of Applied Arts, Vienna (Österreichisches Museum für angewandte Kunst or MAK), with the rest spread over many collections. The Victoria and Albert Museum possess 27 images, bought in Kashmir, and the British Museum in London has one. The MAK organized in 2009 the exhibition GLOBAL:LAB, Art as a Message. Asia and Europe 1500-1700, which showed its whole holding of the Hamzanama. Other recent exhibitions dedicated to the manuscript have been at the Victoria and Albert Museum in 2003 and in 2002/2003 at the Smithsonian in Washington D.C. which transferred to the Brooklyn Museum in New York.

Whole miniature of Mughal Hamzanama trace by John seyller in his book “The adventures of Hamza : painting and storytelling in Mughal India”

Other versions

The Dastan-e-Amir Hamza existed in several other illustrated manuscript versions. One version by Navab Mirza Aman Ali Khan Ghalib Lakhnavi was printed in 1855 and published by the Hakim Sahib Press, Calcutta, India. This version was later embellished by Abdullah Bilgrami and published by the Naval Kishore Press, Lucknow, in 1871. Two English language translations have been published. The first is available in an expanded version on the website of the translator Frances Pritchett, of Columbia University. Pritchett’s former student at Columbia University, Pasha Mohamad Khan, who currently teaches at McGill University, researches qissa/dastan (romances) and the art of dastan-goi (storytelling), including the Hamzanama. In 2007 Musharraf Ali Farooqi, a Pakistani-Canadian author, translated the Ghalib Lakhnavi/Abdulla Bilgriami version into English.

A Pakistani author Maqbool Jahangir wrote Dastan-e-Amir Hamza for children in Urdu language. His version contains 10 volumes and was published by Ferozsons (also Ferozsons Publishers).

The story is also performed in Indonesian puppet theatre, where it is called Wayang Menak. Here, Hamzah is also known as Wong Agung Jayeng Rana or Amir Ambyah.

Characters

Qubad Kamran The king of Iran

Alqash Grand Minister of Qubad Kamran and an astrologer

Khawaja Bakht Jamal A descendant of Prophet Daniel (not in reality) who knows of astrology and became teacher and friend of Alqash.

Bozorgmehr Son of Khawaja Bakht Jamal, a very wise, noble and talented astrologer who became Grand Minister of Qubad Kamran.

Source from Wikipedia