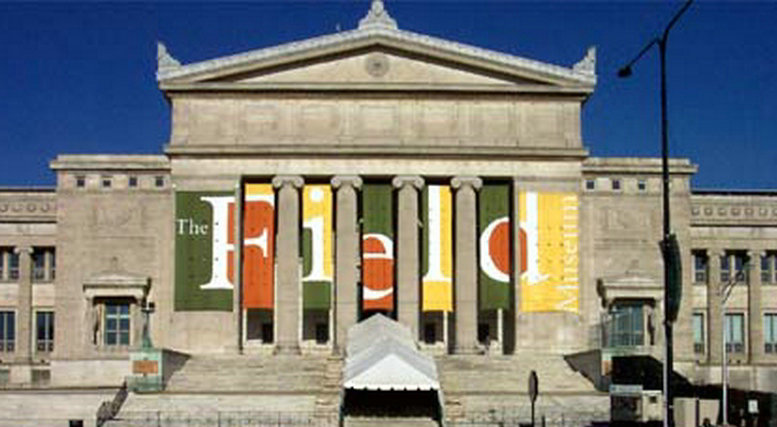

The Field Museum of Natural History, also known as The Field Museum, is a natural history museum in the city of Chicago, and is one of the largest such museums in the world. The museum maintains its status as a premier natural history museum through the size and quality of its educational and scientific programs, as well as due to its extensive scientific specimen and artifact collections. The diverse, high quality permanent exhibitions, which attract up to two million visitors annually, range from the earliest fossils to past and current cultures from around the world to interactive programming demonstrating today’s urgent conservation needs. It is named in honor of its first major benefactor, Marshall Field.

One of the world’s leading natural history museums, The Field Museum is home to more than 30 million artifacts and specimens, exciting exhibitions, and more than 150 scientists, conservators, and collections staff. The Field Museum inspires curiosity about life on Earth while exploring how the world came to be and how we can make it a better place.

Additionally, the Field Museum maintains a temporary exhibition program of traveling shows as well as in-house produced topical exhibitions. The professional staff maintains collections of over 24 million specimens and objects that provide the basis for the museum’s scientific research programs. These collections include the full range of existing biodiversity, gems, meteorites, fossils, as well as rich anthropological collections and cultural artifacts from around the globe. The Field Museum Library, which contains over 275,000 books, journals, and photo archives focused on biological systematics, evolutionary biology, geology, archaeology, ethnology and material culture, supports the Field Museum’s academic research faculty and exhibit development.

The Field Museum academic faculty and scientific staff engage in field expeditions, in biodiversity and cultural research on all continents, in local and foreign student training, in stewardship of the rich specimen and artifact collections, and work in close collaboration with public programming exhibitions and education initiatives.

History:

The Field Museum was primarily an outgrowth of the World’s Columbian Exposition held in Chicago in 1893. The first published suggestion that a museum should be formed as a result of the exposition was, in the opinion of Frederick J.V. Skiff, first Director of the Museum, an article by Professor F.W. Putnam in the Chicago Tribune of May 31, 1890. In that year and the following one Putnam also addressed local bodies on this subject and his views were duly reported in the newspapers.

The Field Museum and its collections originated from the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition and the artifacts displayed at the fair. In order to house the exhibits and collections assembled for the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair for future generations, Edward Ayer convinced the merchant Marshall Field to fund the establishment of a museum. Originally titled the Columbian Museum of Chicago in honor of its origins, the Field Museum was incorporated by the State of Illinois on September 16, 1893, for the purpose of the “accumulation and dissemination of knowledge, and the preservation and exhibition of artifacts illustrating art, archaeology, science and history.” The Columbian Museum of Chicago occupied the only building remaining from the World’s Columbian Exposition in Jackson Park, the Palace of Fine Arts, which now houses the Museum of Science and Industry.

These funds enabled purchases to be made of large collections or important exhibits that had been shown at the exposition. Such purchases included those the War natural history collection, the Tiffany collection of gems, the collection of pre-Columbian gold ornaments, the Hassler ethnological collection from Paraguay, collections representing Javanese, Samoan and Peruvian ethnology, and the Hagenbeck collection of about 600 ethnological objects from Africa, the South Sea Islands, British Columbia, et cetera.

A spirit of generous cooperation was aroused on all sides, and donations of exhibits and collections of great value were received in large numbers. Mr. Ayer presented his large anthropological collection, chiefly devoted to the ethnology of the North American Indian. The Museum acquired by purchase and by gift almost all the extensive collections made by the department of anthropology of the exposition. The technical and special collections made by the department of mines, mining and metallurgy of the exposition were presented, together with the exhibition cases, as were also collections from 130 exhibitors in the same department. From exhibitors in agriculture, forestry and manufactures departments of the exposition collections of timbers, oils, gums, resins, fibers, fruits, seeds and grains were contributed in so large quantity and variety as to insure for the first time in any general natural history museum the formation of an adequate department of botany.

In 1905, the museum’s name was changed from Columbian Museum of Chicago to Field Museum of Natural History to honor its first major benefactor, Marshall Field, and to reflect its focus on the natural sciences. During the period from 1943 to 1966, the museum was known as the Chicago Natural History Museum. In 1921, the Museum moved from its original location in Jackson Park to its present site on Chicago Park District property near downtown. By the late 1930s the Field emerged as one of the three premier museums in the United States, the other two being the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH, New York) and the National Museum of Natural History (Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC).

The Field Museum has maintained its reputation through continuous growth, expanding the scope of collections and its scientific research output, in addition to the its award-winning exhibitions, outreach publications, and programs. The Field Museum is part of Chicago’s lakefront Museum Campus that includes the John G. Shedd Aquarium and the Adler Planetarium.

Collections:

Professionally managed and maintained specimen and artifact collections, such as those at the Field Museum of Natural History, are a major research resource for the national and international scientific community, supporting extensive research that tracks environmental changes, benefits homeland security, public health and safety, and serves taxonomy and systematics research. Many of Field Museum’s collections rank among the top ten collections in the world, e.g., the bird skin collection ranks fourth worldwide; the mollusk collection is among the five largest in North America; the fish collection is ranked among the largest in the world. The scientific collections of the Field Museum originate from the specimens and artifacts assembled between 1891 and 1893 for the World Columbian Exposition. Already at its founding, the Field Museum had a large anthropological collection. A large number of the early natural history specimens were purchased from Ward’s Natural History Establishment in Rochester, New York. An extensive acquisition program, including large expeditions conducted by the museum’s curatorial staff resulted in substantial collection growth. During the first 50 years of the museum’s existence, over 440 Field Museum expeditions acquired specimens from all parts of the world. In addition, material was added through purchase, such as the Strecker butterfly collection in 1908 for example. Extensive specimen material and artifacts were given to the museum by collectors and donors, such as the Boone collection of over 3,500 East Asian artifacts, consisting of books, prints and various objects. In addition, “orphaned collections” were and are taken in from other institutions such as universities that change their academic programs away from collections-based research. For example, already beginning in 1907, Field Museum accepted substantial botanical specimen collections from universities such as University of Chicago, Northwestern University and University of Illinois at Chicago, into its herbarium. These specimens are maintained and continuously available for researchers worldwide. Targeted collecting in the US and abroad for research programs of the curatorial and collection staff continuously add high quality specimen material and artifacts; e.g., Dr. Robert Inger’s collection of frogs from Borneo as part of his research into the ecology and biodiversity of the Indonesian fauna. Collecting of specimens and acquisition of artifacts is nowadays subject to clearly spelled-out policies and standards, with the goal to acquire only materials and specimens for which the provenance can be established unambiguously. All collecting of biological specimens is subject to proper collecting and export permits; frequently, specimens are returned to their country of origin after study. Field Museum stands among the leading institutions developing such ethics standards and policies; Field Museum was an early adopter of voluntary repatriation practices of ethnological and archaeological artifacts.

Field Museum collections are professionally managed by collection managers and conservators, who are highly skilled in preparation and preservation techniques. In fact, numerous maintenance and collection management tools were and are being advanced at Field Museum. For example, Carl Akeley’s development of taxidermy excellence produced the first natural-looking mammal and bird specimens for exhibition as well as for study. Field Museum curators developed standards and best practices for the care of collections. Conservators at the Field Museum have made notable contributions to the preservation of artifacts including the use of pheromone trapping for control of webbing clothes moths. In a modern collections-bearing institution, the vast majority of the scientific specimens and artifact are stored in specially designed collection cabinets, placed in containers made of archival materials, with labels printed on acid-free paper, and specimens and artifact are stored away from natural light to avoid fading. Preservation fluids are continuously monitored and in many collections humidity and temperature are controlled to ensure the long-term preservation of the specimens and artifacts. Field Museum was an early adopter of positive-pressure based approaches to control of environment in display cases, using control modules for humidity control in several galleries where room-level humidification was not practical. The museum has also adopted a low-energy approach to maintain low humidity to prevent corrosion in archaeological metals using ultra-well-sealed barrier film micro-environments. Other notable contributions include methods for dyeing Japanese papers to color match restorations in organic substrates, the removal of display mounts from historic objects, testing of collections for residual heavy metal pesticides, presence of early plastics in collections, the effect of sulfurous products in display cases, and the use of light tubes in display cases. Concordant with research developments, new collection types, such as frozen tissue collections, requiring new collecting and preservation techniques are added to the existing holdings.

Collection management requires meticulous record keeping. Handwritten ledgers captured specimen and artifact data in the past. Field Museum was an early adopter of computerization of collection data beginning in the late 1970. Field Museum contributes its digitized collection data to a variety of online groups and platforms, such as: HerpNet, VertNet and Antweb, Global Biodiversity Information Facility or GBif, and others. All Field Museum collection databases are unified and currently maintained in KE EMu software system. The research value of digitized specimen data and georeferenced locality data is widely acknowledged, enabling analyses of distribution shifts due to climate changes, land use changes and others.

During the World’s Columbian Exposition, all acquired specimens and objects were on display; the purpose of the World’s Fair was exhibition of these materials. For example, right after opening of the Columbian Museum of Chicago the mollusk collection occupied one entire exhibit hall, displaying 3,000 species of mollusks on about 1,260 square feet. By 1910, 20,000 shell specimens were on display, with an additional 15,000 ‘in storage’.

In today’s museum, only a small fraction of the specimens and artifacts are publicly displayed. The vast majority of specimens and artifacts are used by a wide range of people in the museum and around the world. Field Museum curatorial faculty and their graduate students and postdoctoral trainees use the collections in their research and in training e.g., in formal high school and undergraduate training programs. Researchers from all over the world can search online for particular specimens and request to borrow them, which are shipped routinely under defined and published loan policies, to ensure that the specimens remain in good condition. For example, in 2012, Field Museum’s Zoology collection processed 419 specimen loans, shipping over 42,000 specimens to researchers, per its Annual Report. The collection specimens are an important cornerstone of research infrastructure in that each specimen can be re-examined and with the advancement of analytic techniques, new data can be gleaned from specimens that may have been collected more than 150 years ago.

On May 17, 2000, the Field Museum unveiled Sue, the most complete and best-preserved Tyrannosaurus rex fossil yet discovered. Sue is 12.3 m (40 feet) long, stands 3.66 m (12 feet) high at the hips and is 67 million years old. The fossil was named after the person who discovered it, Sue Hendrickson, and is commonly referred to as female, though the fossil’s actual sex is unknown. The original skull, located on the balcony overlooking Sue, was not mounted to the body due to the difficulties in examining the specimen 13 feet off the ground, and for nominal aesthetic reasons (the replica does not require a steel support under the mandible). An examination of the bones revealed that Sue died at age 28, a record for the fossilized remains of a T. rex.

Exhibitions:

Animal exhibitions and dioramas such as Nature Walk, Mammals of Asia, and Mammals of Africa that allow visitors an up-close look at the diverse habitats that animals inhabit. Most notably featured are the infamous Lions of Tsavo

The Grainger Hall of Gems and its large collection of diamonds and gems from around the world, and also includes a Louis Comfort Tiffany stained glass window. The Hall of Jades focuses on Chinese jade artifacts spanning 8,000 years.

The Underground Adventure gives visitors a bugs-eye look at the world beneath their feet. Visitors can see what insects and soil look like from that size, while learning about the biodiversity of soil and the importance of healthy soil.

Inside Ancient Egypt offers a glimpse into what life was like for ancient Egyptians. Twenty-three human mummies are on display as well as many mummified animals. The exhibit features a tomb that visitors can enter, complete with 5,000-year-old hieroglyphs. There are also many interactive displays, for both children and adults, as well as a shrine to the cat goddess Sekhmet and her kinder, less hostile form, Bastet. A popular feature of the exhibit is the replica (with original materials) of the chapel in the tomb of Unis-Ankh, the son of Unas (the last pharaoh of the Fifth Dynasty).

Evolving Planet follows the history and the evolution of life on Earth over 4 billion years, from the first organism to present-day life. Visitors can see how mass extinctions in Earth’s history helped shape all the organisms. There is also an expanded dinosaur hall, with dinosaurs from every era, as well as interactive displays.

The Ancient Americas displays 13,000 years of human ingenuity and achievement in the Western Hemisphere, where hundreds of diverse societies thrived long before the arrival of Europeans. In this large permanent exhibition visitors can learn the epic story of the peopling of these continents, from the Arctic to the tip of South America.

DNA Discovery Center – Visitors can watch real scientists extract DNA from a variety of organisms. Museum goers can also speak to a live scientist through the glass every day and ask them any questions about DNA.

McDonald’s Fossil Prep Lab – The public can watch as paleontologists prepare real fossils for study.

The Regenstein Pacific Conservation Laboratory – 1,600-square-foot (150 m2) conservation and collections facility. Visitors can watch as conservators work to preserve and study anthropological specimens from all over the world.

Other exhibitions include sections on Tibet and China, where visitors can view traditional clothing. There is also an exhibit on life in Africa, where visitors can learn about the many different cultures on the continent and an exhibit where visitors may “visit” several Pacific Islands. The museum houses an authentic 19th century Māori Meeting House, Ruatepupuke II, from Tokomaru Bay, New Zealand. There are also a few vintage Mold-A-Rama machines that create injection-molded plastic dinosaurs collected by Chicago children.

Library:

The library at the Field Museum was organized in 1893 for the museum’s scientific staff, visiting researchers, students, and members of the general public as an resource for research, exhibition development and educational programs. The 275,000 volumes of the Main Research Collections concentrate on biological systematics, environmental and evolutionary biology, anthropology, botany, geology, archaeology, museology and related subjects. The Field Museum Library includes the following collections:

This private collection of Edward E. Ayer, the first president of the museum, contains virtually all the important works in the history of ornithology and is especially rich in color-illustrated works.

The working collection of Dr. Berthold Laufer, America’s first sinologist and Curator of Anthropology until his death in 1934 consists of about 7,000 volumes in Chinese, Japanese, Tibetan, and numerous Western languages on anthropology, archaeology, religion, science, and travel.

The Photo Archives contain over 250,000 images in the areas of anthropology, botany, geology and zoology and documents the history and architecture of the museum, its exhibitions, staff and scientific expeditions. In 2008 two collections from the Photo Archives became available via the Illinois Digital Archives (IDA): The World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 and Urban Landscapes of Illinois. In April 2009, the Photo Archives became part of the Flickr Commons.

The Karl P. Schmidt Memorial Herpetological Library, named for Karl Patterson Schmidt is a research library containing over 2,000 herpetological books and an extensive reprint collection.

Research:

The Field Museum offers opportunities for informal and more structured public learning. Exhibitions remain the primary means of informal education, but throughout its history the Museum has supplemented this approach with innovative educational programs. The Harris Loan Program, for example, begun in 1912, reaches out to children in Chicago area schools, offering artifacts, specimens, audiovisual materials, and activity kits. The Department of Education, begun in 1922, offers classes, lectures, field trips, museum overnights and special events for families, adults and children. The Field has adopted production of the YouTube channel The Brain Scoop, hiring its host Emily Graslie full-time as ‘Chief Curiosity Correspondent’.

The Museum’s curatorial and scientific staff in the departments of Anthropology, Botany, Geology, and Zoology conducts basic research in systematic biology and anthropology, besides its responsibility for collections management, and educational programs. Since its founding the Field Museum has been an international leader in evolutionary biology and paleontology, and archaeology and ethnography. It has long maintained close links, including joint teaching, students, seminars, with the University of Chicago and the University of Illinois at Chicago. Professional symposia and lectures, like the annual A. Watson Armour III Spring Symposium, present scientific results to the international scientific community and the public at large.