A heterogeneous mass of consumers arose during the first half of the nineteenth century, something never previously seen in Austrian cultural history. With the effects of the Industrial Revolution and the growing cultural, social, and economic strength of the middle class, it became both possible and necessary to produce differentiated products for these consumers. It now became both necessary and possible to put at the disposal of the more general public items that had previously only been available to a small circle of consumers. Besides the wide variety of tastes, the range of products on offer was therefore also marked by a subtle gradation from expensive luxury items to cheap substitutes. A generally understood language for materials and forms thus emerged, which was no longer specific to any particular social stratum, but instead determined by financial factors. The depictions were no longer symbolic in character, but were related to real people, things, and events.

The selection of objects displayed here therefore shows, alongside outstanding achievements of Austrian art and craft production, above all the variety of designs and materials used for everyday commodities during the Empire and Biedermeier period. The explosion of richly varying forms is demonstrated by a series of variations in chairs, porcelain cups with a limitless range of moods, glasses conveying all sorts of information, and silverware pieces with designs ranging in character from abstract to decorative.

Jenny Holzer never liked museum labels and brochures. She wanted to find another system to present information about the collection and about the times in which the objects were made. She tried to think of an appealing way to show a super-abundance of text on Biedermeier and Empire. She chose electronic signs with large memories to talk about why what was produced for whom. The signs display the predictable facts, and softer material such as personal letters of the period. Because some people hate to read in museums, She placed the signs near the ceiling so they can be ignored. To encourage people who might read, I varied the signs’ programs and included special effects. For serious, exhausted readers, she provided an aluminum mock-Biedermeier sofa on which to sit. She also rearranged the furniture, silverware, glassware, and porcelain, as would any good housewife.

The media artist Jenny Holzer investigates the means and possibilities for disseminating her own ideas and artistic concerns in public space. Since the 1970s, she has been using such media that allow her work to blend with its environment. The texts in her work are comments that harmonize with their surroundings. They stimulate perception and confront the viewer with social circumstances that are communicated by the specific conditions of the site.

Furniture and woodwork Collection

The main focus of the MAK Furniture and Woodwork Collection is on Baroque and Rococo furniture, Empire and Biedermeier furniture as well as Historicism and Art Nouveau furniture, each represented by outstanding examples.

Other highlights include Gothic and Renaissance furniture, on which the museum’s collection policy focused primarily when it was founded, simple and practical furniture from the period around 1900, an extraordinary collection of furniture from the Viennese interwar period that spanned the period 1918 to 1938 in a unique way documented, as well as contemporary furniture since about the 1960s. The MAK also has excellent holdings of courtly furniture from Austria and Vienna as well as original and copied English furniture from around 1900.

Central stages of the design history trace the proven collection of bentwood furniture as well as the unique collection of furniture and objects from the Wiener Werkstätte.

The artistic highlights as well as a large part of the historically most important objects of this collection segment are presented in the MAK’s permanent collection according to style-historical criteria. For example, the Historicism Art Nouveau permanent collection shows an overview of one hundred years of Thonet furniture production and that of competing companies from the 1930s to the 1930s.

The exhibits in the Baroque Rococo Classicism collection are particularly worth seeingpresented an art cabinet (Neuwied am Rhein, 1776) made by David Roentgen for the Governor General of the Netherlands, Prince Karl Alexander of Lorraine, which is considered the highlight of German cabinet making.

The diverse typology of seating furniture in different eras was visible in the seating furniture study collection from 1993 to 2013: Here, different or identical types, functions, development levels and materials of seating furniture were compared.

During the Second World War, significant historical holdings of the MAK furniture and woodwork collection were lost: almost a third of the furniture collection was destroyed by the war. In the course of the museum reorganization in the late 1930s and early 1940s, almost the entire inventory of wooden sculptures was given to the Kunsthistorisches Museum; a significant part of the English and Austrian furniture from the turn of the century was lost.

After the war ended, the museum made intensive efforts to rebuild the furniture department. With new purchases, an attempt was made to acquire representative examples of the Wiener Werkstätte and the period between the wars. The Biedermeier, Historism and Art Nouveau collections were completed, and more recent positions since the 1960s have been documented since around the 1980s. The order of the collection has changed from material classification to a typological classification: The furniture collection has long since ceased to include only objects made of wood, but also furniture made of tubular steel, plastic, cardboard or felt.

The border area between art, architecture and furniture design emerges as a new focus of the collectionMAK Collection Contemporary Art plays a central role. Contemporary purchases by Donald Judd, Ron Arad, Tom Dixon and Jerszy Seymour, for example, mark new positions in experimental furniture design.

Museum of Applied Arts, Vienna

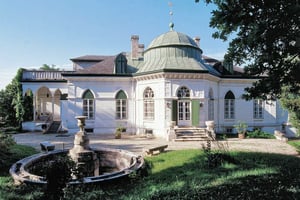

The MAK – Museum of Applied Arts is one of the most important museums of its kind worldwide. Founded as the Imperial Royal Austrian Museum of Art and Industry in 1863, today’s museum—with its unique collection of applied arts and as a first-class address for contemporary art—can boast an incomparable identity. Originally established as an exemplary source collection, today’s MAK Collection continues to stand for an extraordinary union of applied art, design, contemporary art and architecture.

The MAK is a museum and laboratory for applied art at the interface of design, architecture and contemporary art. His core competency is dealing with these areas in a contemporary way, in order to create new perspectives based on the tradition of the house and to explore border areas.

The spacious halls of the Permanent Collection in the magnificent Ringstraße building by Heinrich von Ferstel were later redesigned by contemporary artists in order to present selected highlights from the MAK Collection. The MAK DESIGN LAB expands our understanding of design—a term that is traditionally grounded in the 20th and 21st centuries—by including previous centuries, thereby enabling a better evaluation of the concept of design today. In temporary exhibitions, the MAK presents various artistic stances from the fields of applied arts, design, architecture, contemporary art, and new media, with the mutual relationships between them being a consistently emphasized theme.

It is particularly committed to the corresponding recognition and positioning of applied art. The MAK develops new perspectives on its rich collection, which spans different eras, materials and artistic disciplines, and develops them rigorously.