Biphasic sleep (or diphasic, bimodal or bifurcated sleep) is the practice of sleeping during two periods over 24 hours, while polyphasic sleep refers to sleeping multiple times – usually more than two. Each of these is in contrast to monophasic sleep, which is one period of sleep over 24 hours. Segmented sleep and divided sleep may refer to polyphasic or biphasic sleep, but may also refer to interrupted sleep, where the sleep has one or several shorter periods of wakefulness. A common form of biphasic or polyphasic sleep includes a nap, which is a short period of sleep, typically taken between the hours of 9 am and 9 pm as an adjunct to the usual nocturnal sleep period.

The term polyphasic sleep was first used in the early 20th century by psychologist J. S. Szymanski, who observed daily fluctuations in activity patterns (see Stampi 1992). It does not imply any particular sleep schedule. The circadian rhythm disorder known as irregular sleep-wake syndrome is an example of polyphasic sleep in humans. Polyphasic sleep is common in many animals, and is believed to be the ancestral sleep state for mammals, although simians are monophasic.

The term polyphasic sleep is also used by an online community that experiments with alternative sleeping schedules to achieve more time awake each day. However, researchers such as Piotr Woźniak warn that such forms of sleep deprivation are not healthy. While many claim that polyphasic sleep was widely used by some polymaths and prominent people such as Leonardo da Vinci, Napoleon, and Nikola Tesla, there are few reliable sources supporting that view.

Theory

The most common sleep pattern, known as single-phase sleep, consists of several phases, some of which are long as they naturally occur. The brain initially resists shorter and more frequent periods of sleep, but when it comes to the polyphasic sleep pattern, it learns to enter the essential stages of sleep much faster, as a survival strategy.

This period of adaptation tends to dissipate in two weeks of practice and the symptoms of fatigue are completely overcome after 14 days. However, poor planning of the sleep schedule can complicate or completely frustrate the process. Once the adjustment period is over, all balance is restored and naps replace sleep for long periods.

Polyphasic sleep of normal total duration

An example of polyphasic sleep is found in patients with irregular sleep-wake syndrome, a circadian rhythm sleep disorder which usually is caused by neurological retardation, head injury or dementia. Much more common examples are the sleep of human infants and of many animals. Elderly humans often have disturbed sleep, including polyphasic sleep.

In their 2006 paper “The Nature of Spontaneous Sleep Across Adulthood”, Campbell and Murphy studied sleep timing and quality in young, middle-aged, and older adults. They found that, in free-running conditions, the average duration of major nighttime sleep was significantly longer in young adults than in the other groups. The paper states further:

Whether such patterns are simply a response to the relatively static experimental conditions, or whether they more accurately reflect the natural organization of the human sleep/wake system, compared with that which is exhibited in daily life, is open to debate. However, the comparative literature strongly suggests that shorter, polyphasically-placed sleep is the rule, rather than the exception, across the entire animal kingdom (Campbell and Tobler, 1984; Tobler, 1989). There is little reason to believe that the human sleep/wake system would evolve in a fundamentally different manner. That people often do not exhibit such sleep organization in daily life merely suggests that humans have the capacity (often with the aid of stimulants such as caffeine or increased physical activity) to overcome the propensity for sleep when it is desirable, or is required, to do so.

Comparison of sleep patterns

| sleep patterns | entire sleeping time | REM Number | method |

|---|---|---|---|

| monophasic | ≈ 8.0 hours | 5 phases | 8 hours main sleep phase with five REM phases |

| Divided up | ≈ 7 hours | 4 phases | 2 × 3.5 hours main sleep phase with 2 REM phases each |

| Biphasic (20-minute nap) | ≈ 6.3 hours | 5 phases | 6 hours main sleep phase with four REM phases and a 20 minute ” daytime sleep ” with a REM phase |

| Biphasic (90-minute nap) | ≈ 6 hours | 4 phases | 4.5 hours main sleep phase with three REM phases and a 90 minute sleep with a REM phase |

| triphasic | ≈ 4.5 hours | 3 phases | three times 1.5 hours nap, each with a REM phase |

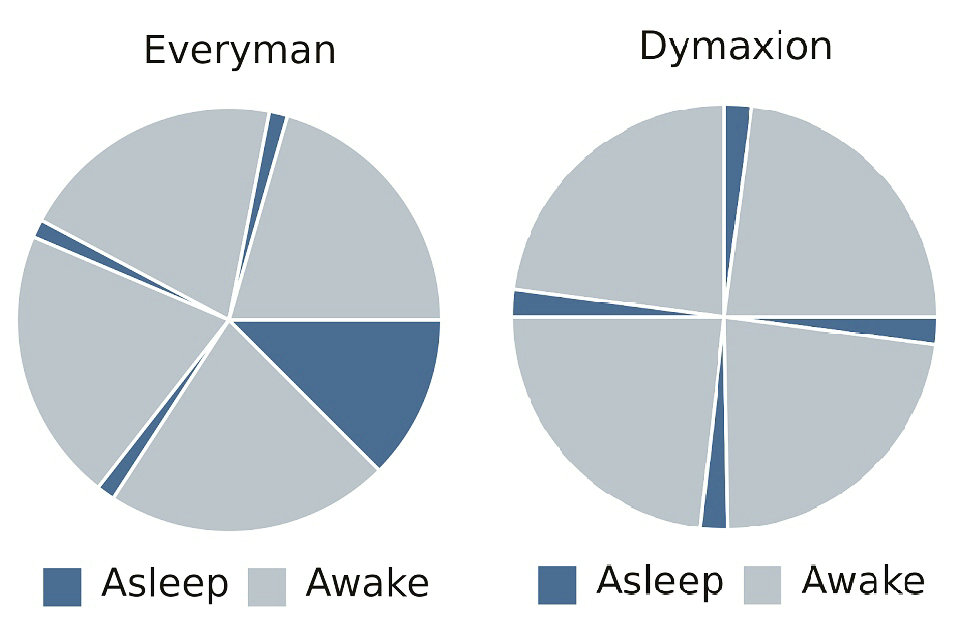

| Everyman (“Everyman”, with two nap) | 5.2 hours | 5 phases | 4.5 hours main sleep phase with three REM phases and two 20-minute day sleep phases with one REM phase each |

| Everyman (“Everyman”, with three naps) | 4 hours | 5 phases | 3 hours main sleep phase with two REM phases and three 20 minute daytime sleep phases with one REM phase each |

| Everyman (“Everyman”, with four to five naps) | ≈ 3 hours | 5-6 phases | 1.5 hours main sleep phase with one REM phase and four to five 20 minute daytime sleep phases with one REM phase each |

| Dymaxion | 2 hours | 4 phases | four times 30 minutes nap with one REM-phase (every 6 hours) |

| Uberman (“Superman”) | 2 hours | 6 phases | six times 20 minutes nap with one REM-phase (every 4 hours) |

According to Süddeutscher Zeitung , the “Uberman” appeared on the Internet at the beginning of the millennium, when an American woman under the pseudonym PureDoxyK reported that she had been practicing this pattern for months as a college student . However, this pattern has two prerequisites: unconditional discipline in keeping the nap and condition in the approximately ten-day transition period.

Adherence to sleep times

Polyphasic sleep requires strict adherence to sleep times. Sleeping times must be evenly distributed and adhered to precisely, as sleeping or skipping sleep results in a drastic drop in performance. Even with monophasic sleep, this leads to a drop in performance, which, however, usually does not turn out as drastically as with polyphasic sleep.

It is particularly problematic that regularly sleeping accommodations must be visited, in which the sleep is not disturbed. This is a hindrance, for example, for longer trips and activities. Even the professional life is usually adapted to the monophasic sleep pattern, which can lead to collisions.

These effects are stronger, the more sleep phases the respective sleep pattern provides.

Another obstacle is the acclimatization phase, which takes about two to three weeks.

Followers of polyphasic sleep usually end their sleep with an alarm clock. In contrast, practitioners of biphasic sleep (night sleep and nap) often wake up without an alarm clock.

Functionality

The usual night sleep lasting about 8 hours is divided into a total of 5 sleep phases, each lasting about 90 minutes. Towards the end of a sleep phase, REM sleep, which is valuable for mental recovery, is achieved.

“Polyphasic sleep” aims to achieve as much REM sleep as possible with as little total sleep as possible. Basically, this is nothing more than stringing together multiple poweraps.

However, by antraining in the acclimation of about 10 days, the proportion of the REM phase z. For example, in the Uberman within the 20 minutes increased so that you reach a total of 2 hours of sleep equivalent to the normal 8-hour night sleep total duration of REM sleep. Here, the so-called “REM rebound” effect plays a role.

Mechanism

According to Dr. Claudio Stampi’s book “Why We Nap, Evolution, Chronobiology, and Functions of Polyphasic and Ultrashort Sleep”, on sleep deprivation, measurement and control of polyphasic sleep, memory and analytical ability present improvements when compared with monophasic or biphasic sleep (although it represents an average of 12% when compared to free sleep, without programming).

According to Stampi, this improvement is due to the extraordinary evolutionary predisposition to adopt such a model. He launches the hypothesis that polyphasic sleep is the closest to sleep habits of human ancestors used for thousands of years, especially when compared to biphasic sleep established after the advent of agriculture and industrial single-phase sleep.

There are at least two schools of thought on how polyphasic sleep affects the sleep pattern. One of the schools advocates that REM is the most important and necessary stage, and that the body needs multiple hours of this stage per day, so that an established nipple sleep in the polyphasic sleep is composed entirely of the REM stage. Another school of researchers suggests that the body goes into different stages, at different sleep intervals.

The idea that polyphasic sleep is composed only by the REM period is relatively popular among its adherents, probably because it suggests that this is the reason for the mentally rejuvenating effect of this sleep pattern. However, this is a controversial subject, still not scientifically established. It has been proven that sleep deprivation can lead to death in mice over a period of 3 to 8 weeks, but the notion that the REM stage is the most important stage of sleep or even necessary for good health is still doubtful: depressed people have excessive REM stages and the MAO Inhibitors used in these cases do not negatively affect cognition, attention or memory, although they virtually cancel out the REM stages.

Classifications

The term polyphasic sleep alone only means sleeping multiple times in a 24-hour period, but does not suggest any particular timing. In this way, specific names are used to designate different methods:

“Uberman” is the name given to the most rigid and well-known type of polyphasic sleep. It consists of six 20-minute naps. According to neurologist Claudio Stampi, creator of the Chronobiology Research Institute in Boston, USA, polyphasic sleep works best when it is not done at strict times. “You’ll have the best time when you feel it’s the right time to sleep. It’s like a train that you should get, but you do not have the right time to go,” and you should not go past the 20-minute nap. By passing this limit, the person goes into a deeper sleep and it becomes more difficult to wake up.

“Everyman” is a Uberman variant in which a longer sleep block is added to the schedule by replacing one or two of the naps. The term is also used to describe a longer period of accidental sleep, which eventually occurs for people in the Uberman method.

Buckminster Fuller suggested in one issue of Time magazine in October 1943 another variant of the polyphasic sleep named ” Dymaxion Sleep.” The regimen consists of sleep periods of 30 minutes every six hours. According to the article, Fuller followed this method for two years before abandoning him because of conflicts with his partners who “insisted on continuing to sleep as they used to.”

Application

Polyphasic sleep is used when sleep periods need to be minimized over a long period of time. This is about athletes. As in the multi-day cycling race RAAM and Weltumseglern, the case.

Polyphase sleep in practice

The most common examples are the sleep regimes of infants, the elderly and many animals. In a 2006 paper, “The Nature of Spontaneous Sleep in Adulthood,” Campbell and Murphy studied the duration and quality of sleep in young, middle-aged and elderly people. They found that in free conditions, the average duration of the main night’s sleep was significantly greater in young people than in other groups.

The question that such models is a simple reaction to the relatively static experimental conditions, or they more accurately reflect the natural organization of the person’s sleep / wake system, compared to what is manifested in everyday life, is open to discussion. Nevertheless, a comparison of the literature suggests that polyphasic sleep should be considered a rule rather than an exception for the entire animal kingdom (Campbell & Tobler, 1984; Tobler, 1989). There is little reason to believe that the human sleep / wake system will evolve on a fundamentally different basis. The fact that people often do not show this kind of sleep organization in everyday life simply suggests that people have the opportunity (often with the help of stimulants such as caffeine or increased physical activity) to overcome the tendency to sleep.

Buckminster Fuller made the first of the documented transitions to polyphasic sleep. Fuller’s experiments with sleep were conducted in the mid-1900s and developed a regime called “Dimaxion” (the same name Fuller gave his trademark that combined several inventions). In Time magazine on October 11, 1942, there was a short article devoted to this method. According to her, the author adhered to this schedule for two years, but then he had to stop this occupation, because “his schedule was contrary to the schedule of his companions who insisted on sleeping like normal people.” The doctors who examined him concluded that he was healthy.

In 2006, American blogger Steve Pavlinafor 5.5 months he lived in a mode of polyphasic sleep (Uberman), laying out in his blog detailed reports on the progress of his experiment. His records are still the most comprehensive guide to the transition to polyphase sleep. In the process of tuning to polyphasic sleep, Steve identifies the stages of physiological and psychological adaptation. After spending several weeks adapting, Steve reports the complete disappearance of negative side effects (drowsiness, physical ailments, etc.). Adapted to the polyphase regime, the author conducts (and describes in detail) a series of experiments (stretching phases, skipping one phase, studying the effect of coffee on the sleeping polyphasic body, etc.). After 5.5 months of polyphasic sleep, Steve returns to monophasic mode, explaining his decision by the lack of synchronization with the surrounding world, living in monophasic mode.

Quick sleep in extreme situations

It often happens that people can not be able to achieve the recommended eight hours of sleep per day. Systematic daytime sleep can be considered necessary in such situations. Dr. Claudio Stumpy, as a result of his interest in single rowing for long distances, studied systematic short-term drowsiness as a means of ensuring optimal performance in situations of extreme sleep deprivation. In the course of his experiments, he examined the Swiss actor Francesco Jost, who tried to master the technique of polyphasic sleep for 49 days at home. At first, the body of Jost experienced a shock, but then the concentration of his attention and mental state came in relative norm, although at times it was difficult to wake up to him. With minimal side effects, the actor managed to reduce the usual time of his sleep by five hours, but the long-term effect was not studied. According to his book, in conditions of deprivation of sleep, the ability to memorize and analyze in practitioners polyphasic sleep increases in comparison with practicing monophasic or biphasic. According to Stumpy, the improvement is the result of an unusual evolutionary predisposition to this mode of sleep. He puts forward a hypothesis that the reason for this may be the propensity to such a regime of distant ancestors of man for thousands of years before the transition to monophasic sleep. It is known[To whom? ] that 1-3% of the world’s population naturally need a very short duration of sleep[ source not specified 315 days ]. This ability is given to them by the mutated gene DEC2.

A study by Thomas Vera

In one experiment, eight healthy men were in the room for 14 hours of darkness daily for a month. At first the participants slept for about 11 hours, making up for a lack of sleep. They slept for about 4 hours, woke up for 2-3 hours, and then returned to bed for another 4 hours. They also took about two hours to fall asleep.

In extreme situations

In crises and other extreme conditions, people may not be able to achieve the recommended eight hours of sleep per day. Systematic napping may be considered necessary in such situations.

Claudio Stampi, as a result of his interest in long-distance solo boat racing, has studied the systematic timing of short naps as a means of ensuring optimal performance in situations where extreme sleep deprivation is inevitable, but he does not advocate ultrashort napping as a lifestyle. Scientific American Frontiers (PBS) has reported on Stampi’s 49-day experiment where a young man napped for a total of three hours per day. It purportedly shows that all stages of sleep were included. Stampi has written about his research in his book Why We Nap: Evolution, Chronobiology, and Functions of Polyphasic and Ultrashort Sleep (1992). In 1989 he published results of a field study in the journal Work & Stress, concluding that “polyphasic sleep strategies improve prolonged sustained performance” under continuous work situations.

U.S. military

The U.S. military has studied fatigue countermeasures. An Air Force report states:

Each individual nap should be long enough to provide at least 45 continuous minutes of sleep, although longer naps (2 hours) are better. In general, the shorter each individual nap is, the more frequent the naps should be (the objective remains to acquire a daily total of 8 hours of sleep).

Canadian Marine pilots

Similarly, the Canadian Marine pilots in their trainer’s handbook report that:

Under extreme circumstances where sleep cannot be achieved continuously, research on napping shows that 10- to 20-minute naps at regular intervals during the day can help relieve some of the sleep deprivation and thus maintain… performance for several days. However, researchers caution that levels of performance achieved using ultrashort sleep (short naps) to temporarily replace normal sleep are always well below that achieved when fully rested.

NASA

NASA, in cooperation with the National Space Biomedical Research Institute, has funded research on napping. Despite NASA recommendations that astronauts sleep eight hours a day when in space, they usually have trouble sleeping eight hours at a stretch, so the agency needs to know about the optimal length, timing and effect of naps. Professor David Dinges of the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine led research in a laboratory setting on sleep schedules which combined various amounts of “anchor sleep”, ranging from about four to eight hours in length, with no nap or daily naps of up to 2.5 hours. Longer naps were found to be better, with some cognitive functions benefiting more from napping than others. Vigilance and basic alertness benefited the least while working memory benefited greatly. Naps in the individual subjects’ biological daytime worked well, but naps in their nighttime were followed by much greater sleep inertia lasting up to an hour.

Italian Air Force

The Italian Air Force (Aeronautica Militare Italiana) also conducted experiments for their pilots. In schedules involving night shifts and fragmentation of duty periods through the entire day, a sort of polyphasic sleeping schedule was studied. Subjects were to perform two hours of activity followed by four hours of rest (sleep allowed), this was repeated four times throughout the 24-hour day. Subjects adopted a schedule of sleeping only during the final three rest periods in linearly increasing duration. The AMI published findings that “total sleep time was substantially reduced as compared to the usual 7–8 hour monophasic nocturnal sleep” while “maintaining good levels of vigilance as shown by the virtual absence of EEG microsleeps.” EEG microsleeps are measurable and usually unnoticeable bursts of sleep in the brain while a subject appears to be awake. Nocturnal sleepers who sleep poorly may be heavily bombarded with microsleeps during waking hours, limiting focus and attention.

Biphasic sleep

An example of a biphasic sleep pattern is the practice of siesta, which is a nap taken in the early afternoon, often after the midday meal. Such a period of sleep is a common tradition in some countries, particularly those where the weather is warm. The siesta is historically common throughout the Mediterranean and Southern Europe. It is the traditional daytime sleep of India, South Africa, Spain, through Spanish influence, China, the Philippines, and many Hispanic American countries. Benefits include boost in cognitive function and stress reduction.

Interrupted sleep

Interrupted sleep is a primarily biphasic sleep pattern where two periods of nighttime sleep are punctuated by a period of wakefulness. Along with a nap in the day, it has been argued that this is the natural pattern of human sleep in long winter nights. A case has been made that maintaining such a sleep pattern may be important in regulating stress.

Historical norm

Historian A. Roger Ekirch has argued that before the Industrial Revolution, interrupted sleep was dominant in Western civilization. He draws evidence from documents from the ancient, medieval, and modern world. Other historians, such as Craig Koslofsky, have endorsed Ekirch’s analysis.

According to Ekirch’s argument, adults typically slept in two distinct phases, bridged by an intervening period of wakefulness of approximately one hour. This time was used to pray and reflect, and to interpret dreams, which were more vivid at that hour than upon waking in the morning. This was also a favorite time for scholars and poets to write uninterrupted, whereas still others visited neighbors, engaged in sexual activity, or committed petty crime.:311–323

The human circadian rhythm regulates the human sleep-wake cycle of wakefulness during the day and sleep at night. Ekirch suggests that it is due to the modern use of electric lighting that most modern humans do not practice interrupted sleep, which is a concern for some writers. Superimposed on this basic rhythm is a secondary one of light sleep in the early afternoon.

The brain exhibits high levels of the pituitary hormone prolactin during the period of nighttime wakefulness, which may contribute to the feeling of peace that many people associate with it.

The modern assumption that consolidated sleep with no awakenings is the normal and correct way for human adults to sleep, may lead people to consult their doctors fearing they have maintenance insomnia or other sleep disorders. If Ekirch’s hypothesis is correct, their concerns might best be addressed by reassurance that their sleep conforms to historically natural sleep patterns.

Ekirch has found that the two periods of night sleep were called “first sleep” (occasionally “dead sleep”) and “second sleep” (or “morning sleep”) in medieval England. He found that first and second sleep were also the terms in the Romance languages, as well as in the language of the Tiv of Nigeria. In French, the common term was premier sommeil or premier somme; in Italian, primo sonno; in Latin, primo somno or concubia nocte.:301–302 He found no common word in English for the period of wakefulness between, apart from paraphrases such as first waking or when one wakes from his first sleep and the generic watch in its old meaning of being awake. In old French an equivalent generic term is dorveille, a portmanteau of the French words dormir (to sleep) and veiller (to be awake).

Because members of modern industrialised societies, with later evening hours facilitated by electric lighting, mostly do not practice interrupted sleep, Ekirch suggests that they may have misinterpreted and mistranslated references to it in literature. Common modern interpretations of the term first sleep are “beauty sleep” and “early slumber”. A reference to first sleep in the Odyssey was translated as “first sleep” in the seventeenth century, but, if Ekirch’s hypothesis is correct, was universally mistranslated in the twentieth.:303

In his 1992 study “In short photoperiods, human sleep is biphasic”, Thomas Wehr had eight healthy men confined to a room for fourteen hours of darkness daily for a month. At first the participants slept for about eleven hours, presumably making up for their sleep debt. After this the subjects began to sleep much as people in pre-industrial times were claimed to have done. They would sleep for about four hours, wake up for two to three hours, then go back to bed for another four hours. They also took about two hours to fall asleep.

Scheduled napping to achieve more time awake

Buckminster Fuller

In order to gain more time awake in the day, Buckminster Fuller reportedly advocated a regimen consisting of 30-minute naps every six hours. The short article about Fuller’s nap schedule in Time in 1943, which also refers to such a schedule as “intermittent sleeping”, says that he maintained it for two years, and further notes “he had to quit because his schedule conflicted with that of his business associates, who insisted on sleeping like other men.”

However, it is not clear when Fuller practiced any such sleep pattern and whether it was really as strictly periodic as claimed in that article; it has also been said that he ended this experiment because of his wife’s objections.

Criticism

Piotr Woźniak considers the theory behind severe reduction of total sleep time by way of short naps unsound, arguing that there is no brain control mechanism that would make it possible to adapt to the “multiple naps” system. Woźniak says that the body will always tend to consolidate sleep into at least one solid block, and he expresses concern that the ways in which the polyphasic sleepers’ attempt to limit total sleep time, restrict time spent in the various stages of the sleep cycle, and disrupt their circadian rhythms, will eventually cause them to suffer the same negative effects as those with other forms of sleep deprivation and circadian rhythm sleep disorder. Woźniak further claims to have scanned the blogs of polyphasic sleepers and found that they have to choose an “engaging activity” again and again just to stay awake and that polyphasic sleep does not improve one’s learning ability or creativity.

Critics of polyphasic sleep are concerned with the possibility of this sleep pattern restricting time spent as the perimetric stages of the sleep cycle, thereby disturbing the body’s circadian rhythm. This could cause suffering from the same negative effects found in sleep deprivation as loss of cognitive ability and physical ability, including stress, anxiety, and weakening of the immune system. However, there are no studies demonstrating the negative effect of polyphasic sleep. Critics point to the difficulty some people have of meeting the short sleep intervals when they end up sleeping beyond what is programmed as evidence of the unsustainability of this pattern.

Polyphasic sleep freaks often witness a gain in alertness, but skeptics question whether this is due even to the new sleep pattern or whether it results from the buildup of adrenaline and cortisol when they successfully achieve their sleep goals – after all, less sleep means more time and therefore more productive goals can be achieved during the day. A study published in the Journal of Sleep Research in September 2002 on the effect of naps on productivity demonstrated that 10 minutes of sleep tended to improve productivity more effectively than longer naps.

Many polyphasic sleepers report that the most difficult part of this sleep pattern is to overcome the social aspect, since working hours often do not allow the necessary period of sleep during the day at regular intervals. Personal reports indicate that missing a single nap can have catastrophic consequences on rigid routines such as Uberman, so often even successful people in polyphasic sleep return to the single-phase pattern to satisfy their schedules.

Source from Wikipedia