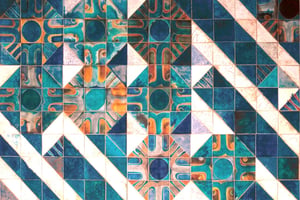

Glazed mosaic pavements have been used in Portugal since the 13th century. They were made of plain coloured geometric pieces, as testified by the examples from the Monastery of Alcobaça and the Castle of Leiria. After the second half of the 15th century, pavings appeared of alfardons with losetas and bricks with rajolas, imported from Manises in Valencia, such as those applied in the Palace of the Infantes in Beja, or the Convent of Jesus in Setúbal. At the start of the 16th century the use of azulejos as a wall revetment became widespread, using patterns in the Hispano-Moresque techniques of corda-seca and aresta, produced in Seville and Toledo. So, Islamic culture was the first great reference for azulejos in Portugal, which lived on in future applications through the aesthetic taste conveying the horror vacui or “fear of the empty”.

The first major Portuguese commission of azulejos produced in Seville was made in 1503 by D. Jorge de Almeida (b.1458 – d.1543), Bishop of Coimbra, for the cathedral in this city. The Romanesque church, including the walls and the pillars, was entirely lined inside with azulejos simulating the presence of textile and architectural elements. Another important moment in the history of azulejos in Portugal in the early 16th century is the huge order placed by D. Manuel I (r. 1495-1521) in 1508, also with the Seville workshops, of azulejos for the palace he was remodelling in the town of Sintra. Azulejos from that commission can still be enjoyed today in many of the palace’s rooms and courtyards, in particular the examples with the armillary sphere, the emblem of this king. Commissions by the clergy and the nobility very often also included the use of heraldic motifs, such as the coat of arms of D. Jaime I (b.1479 – d.1532), fourth Duke of Bragança, composed of four rectangular ceramic plaques. In monumental applications such as those in Coimbra’s old Cathedral or Sintra Royal Palace (Sintra National Palace), Portuguese tile-layers reinvented the Sevillian matrices of applying azulejos, creating compositions of great visual effect, in perfect harmony with the architecture. Thus began the differentiating character of the use of azulejos in Portugal.

Moving forward in the 16th century we realise that the motifs used to decorate the azulejos change gradually. After a first phase when these motifs, such as bows and geometric chains, were obviously of Islamic influence, we move on to a period when the decorative programmes employ initially Gothic and then Renaissance elements. Testimony to the fact that azulejo production adapted to the taste of the era, the new commissions from Seville included essentially vegetalist motifs, although zoomorphic elements and heraldry were also present. The use of the Hispano-Moresque techniques of corda-seca and aresta continued.

Hispanic-Moresque Tile

In the early 16th century, the use of azulejos as a wall revetment became widespread, using patterns in the Hispano-Moresque techniques of corda-seca and aresta, produced in Seville and Toledo.

Islamic culture was the first great reference for azulejos in Portugal, which lived on in future applications through the aesthetic taste conveying the horror vacui or “fear of the empty”.

Faience

Azulejo production began in the second half of the 16th century, in Lisbon. This was encouraged by a number of Flemish artisans that settled in the capital, bringing with them their know-how and experience of the new technique.

The panel known as Nossa Senhora da Vida (Our Lady of Life) is one of the most important pieces in the collection of the National Azulejo Museum and one of the key pieces of 16th century Portuguese production. It was originally applied in the Church of Santo André in Lisbon which was partially destroyed by the 1755.

The panel is painted in “trompe l’oeil”, employs a wide range of tones, and is considered one of the richest to be found in azulejo production of the time.

It simulates a three-part altarpiece composition painted on a surface of 1.498 azulejos, presenting in the centre a painting with the Adoration of the Shepherds. It attempts to imitate a painted board with a fine giltwood carved frame.

Four columns flank the two niches containing images of the Evangelists Saint John and Saint Luke, depicted as sculptures.

Observing this panel one can understand one of the identity aspects of Portuguese azulejos, which is how they are directly related to the space where they were applied.

The fact is that the space, currently empty, in the centre of the panel corresponded in the Church of Santo André to a window. As the light came in through that window it would have symbolically underlined the route taken by the Dove of the Holy Spirit to reach Mary.

This concept of associating architecture to the message intended to be conveyed is one of the central aspects of Portuguese production, one that sets it apart from azulejo production elsewhere.

This panel’s catechist function, with the powerful expression conveyed by the composition’s monumentality and setting, is also paradigmatic of Portuguese azulejos as an art intended to integrally cover and have the capacity to transform architectural structures.

National Azulejo Museum

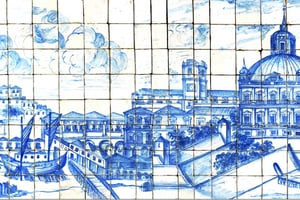

The National Tile Museum of Portugal, is an art museum in Lisbon, Portugal dedicated to the azulejo, traditional tilework of Portugal and the former Portuguese Empire, as well as of other Iberophone cultures. Housed in the former Madre de Deus Convent, the museum’s collection is one of the largest of ceramics in the world.

The Museu Nacional do Azulejo is housed in the former Convent of Madre de Deus founded in 1509 by Queen Leonor. Its collection presents the history of glazed tiles in Portugal, from the second half of the XV Century to the present day, proving that the tile remains a living and an identity expression of Portuguese culture.

Occupying various spaces in the building’s former convent wings, MNAz’s permanent exhibition documents the history of tile in Portugal from the 16th century to the present.

In close connection with the presented tile heritage, other ceramic objects belonging to the museum’s collections are integrated into the expository discourse.