Degenerate art

Degenerate art (German: Entartete Kunst) was a term adopted in the 1920s by the Nazi Party in Germany to describe modern art. During the dictatorship of Adolf Hitler, German modernist art and the works of internationally renowned artists was removed from state owned museums and banned in Nazi Germany on the grounds that it was an “insult to German feeling”, un-German, Jewish, or Communist in nature, and those identified as degenerate artists were subjected to sanctions. These included being dismissed from teaching positions, being forbidden to exhibit or to sell their art, and in some cases being forbidden to produce art.

Degenerate Art also was the title of an exhibition, held by the Nazis in Munich in 1937, consisting of 650 modernist artworks chaotically hung and accompanied by text labels deriding the art. Designed to inflame public opinion against modernism, the exhibition subsequently traveled to several other cities in Germany and Austria.

While modern styles of art were prohibited, the Nazis promoted paintings and sculptures that were traditional in manner and that exalted the “blood and soil” values of racial purity, militarism, and obedience. Similar restrictions were placed upon music, which was expected to be tonal and free of any jazz influences; disapproved music was termed degenerate music. Films and plays were also censored.

Origin of the term “degenerate art”

The word “degenerate” originally comes from Middle High German, where it had the meaning “beaten out of the way”. In the 19th century, the term was first used in the derogatory context when the Romantic Friedrich Schlegel wrote about “degenerate art” in relation to late antiquity. The French diplomat and writer Joseph Arthur Comte de Gobineau 1853 used the term in his essai sur l ‘inégalité des races humaines for the first time in a racially pejorative sense, but without anti-Semitic or German national connotations. Karl Ludwig Schemann, who translated Gobineau’s work into German and published between 1898 and 1901, was a member of the Pan-German Union.

Richard Wagner published in 1850 the article Judaism in music, in which he denounced the influence of Judaism in music and demanded the emancipation of the Jews. Wagner published further theoretical writings in which he also dealt with other art genres and which were partly controversial. In 1892/93, the Jewish cultural critic Max Nordau published his work Degeneracy, in which he tried to prove that the degeneration of art can be traced back to the degeneration of the artist. His theses were later taken up by the National Socialists, by Hitler partly even taken literally. Also emperorIn his notorious dripstone speech on the occasion of the opening of the Siegesallee on 18 December 1901, Wilhelm II made a derogatory comment on modernist art trends.

National Socialists against Modern Art

Defamation of all forms of modern art

The National Socialists developed a separate artistic ideal of a German art and pursued the opposing art, which was also called “decay art” and “alien”, because it was characterized by pessimism and pacifism. Artists whose works did not conform to the National Socialist ideals that were communists or Jews were persecuted. The National Socialists gave them professional and painting bans, removed their works of art from museums and public collections, confiscated “degenerate art”, forced artists to emigrate or murdered them.

There were three consistent defamation measures of the Nazi cultural policy: book burning in May 1933 in Berlin and 21 other cities as well as after Austria’s Anschluss in 1938 there, persecution of painters and their “degenerate art” and persecution of “degenerate music” at the Reich Music Festival 1938 in Dusseldorf.

With the introduction of the Law on the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service of April 7, 1933, with the help of Jewish, Communist and other undesirable artists were removed from public office by force, and the book burning 1933 on May 10, 1933 with the peak on the Berlin Opera Square, was Already in the first months after the seizure of power by the National Socialists it became clear that the diversity of the artistic creation of the Weimar Republic was irrevocably over.

The extermination attack on modernity and its protagonists affected all sectors of culture such as literature, film art, theater, architecture or music. Modern music such as swing or jazz was ruthlessly defamed at the exhibition ” Degenerate Music ” opened on May 24, 1938, as well as the “music bolshevism” by internationally known composers such as Hanns Eisler, Paul Hindemith or Arnold Schoenberg, most of whom also of Jewish origin. In the episode appeared from 1940 the notoriousLexicon of Jews in Music.

1930-1936

The decree “Against the Negro Culture for German Folklore” (April 5, 1930), which was initiated by the National Socialist Education Minister Thuringia Wilhelm Frick, was directed against modern art and was the starting point for the attack on influences in art that were defined as “un-German.” This led in October 1930 to the painting of Oskar Schlemmer wall design of the Weimar workshop building. Next Frick operated the dissolution of the Weimar Bauhaus School and dismissed the faculty. He called Paul Schultze-Naumburg, a leading representative of a right-wing conservative building and cultural ideology, as director of the newly founded Vereinigte Kunstlehranstalten Weimar. Under the direction of the Weimar Castle Museum were works by Ernst Barlach, Charles Crodel, Otto Dix, Erich Heckel, Oskar Kokoschka, Franz Marc, Emil Nolde and Karl Schmidt-Rottluffand others away. Although Minister Frick was deprived of the confidence of the Thuringian Landtag on 1 April 1931, the parliamentary elections of 31 July 1932 gave the Nazi party an absolute majority and opened access from Weimar to Berlin, which consequently led to the example of the in the summer of 1933 some of the baths at Bad Lauchstädt were partly burned and partly painted over, while in Berlin a fierce battle for direction took place, which Alfred Rosenberg won in the winter of 1934/1935 and after the Olympic Games in Berlin 1936 implemented. The artist Emil Bartoschek painted exaggerated naturalistic pictures, which found numerous buyers through a gallery in the Berlin Friedrichstrasse to distract from his abstract painting, which was reserved for a small circle.

1936-1945

The beginning of the new wave of persecution was the closure of the Neue Abteilung of the Nationalgalerie Berlin in the Kronprinzenpalais on October 30, 1936, and the decree of June 30, 1937, which authorized the new Reichskunstkammerpräsident Adolf Ziegler, “the works in German Reich, state and municipal possession German Decay Art since 1910 in the field of painting and sculpture for the purpose of an exhibition to select and ensure “.

In 1936, a total ban on all modern art was done. Hundreds of works of art, especially in the field of painting, were removed from the museums and either confiscated for the exhibition “Degenerate Art”, sold abroad or destroyed. Painters, writers and composers were – as far as they had not emigrated to foreign countries – work and exhibition ban. The ban on the purchase of non-Aryan and modern works of art, which had already existed since 1933, was tightened. The gradual disempowerment of the Jewish population meant that many works of art from their private property fell into the hands of the state and, if they were considered “degenerate”, were destroyed or sold abroad.

Well-known ostracized artists

Immediately after the seizure of power by the National Socialists, they aggressively announced with police-enforced closures of exhibitions and verbal and physical attacks on artists and cultural associations, the line that they intended to enforce in terms of cultural policy in the following years. In response, many artists fled to neighboring Germany. Further escape waves were triggered by the Nuremberg Laws of 1935, as well as by defamation as “degenerate” art and the November pogroms of 1938. For example, 64 Hamburg artists fled to 23 different countries.

As “degenerate” were, among others, the works of Ernst Barlach, Willi Baumeister, Max Beckmann, Karl Caspar, Maria Caspar-Filser, Marc Chagall, Giorgio de Chirico, Lovis Corinth, Otto Dix, Max Ernst, Otto Freundlich, Paul Gauguin, Wilhelm Geyer, Otto Griebel, George Grosz, Werner Heuser, Karl Hofer, Karl Hubbuch, Hans Jürgen Kallmann,Wassily Kandinsky, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Paul Klee, Oskar Kokoschka, Käthe Kollwitz, Wilhelm Lehmbruck, Elfriede Lohse-Wächtler, Gerhard Marcks, Ludwig Meidner, Paula Modersohn-Becker, Piet Mondrian, Rudolf Moller, Otto Pankok, Max Pechstein, Pablo Picasso, Christian Rohlfs, Oskar Schlemmer, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff and Werner Scholz.

The exhibition “Degenerate Art” in Munich 1937

The exhibition “Degenerate Art” was opened on 19 July 1937 in Munich in the Hofgarten Arcades and showed 650 confiscated works of art from 32 German museums. It also migrated to other houses throughout the country and was “presented” to school classes and party-affiliated associations. Over two million visitors saw her. This is much more than the large German art exhibition taking place at the Haus der Deutschen Kunst, which was attended by 420,000 people. The (propagated) interest in the mocked art was so much greater than that at the officially celebrated. The exhibition was initiated by Joseph Goebbels and by Adolf Ziegler, the President of the Reich Chamber of the Fine Arts, headed. At the same time, with the confiscation of a total of about 16,000 modern works of art, some of which were sold or destroyed abroad, the “cleansing” of German art collections began, whereby apparently from museums owned by Jewish collectors. T. also older works of art were concerned.

The exhibition went on a traveling exhibition through the major cities of the Reich. It became Berlin after the annexation of Austria to the German Reich on 13 March 1938, from 7 May to 18 June at the Wiener Künstlerhaus, from 4 to 25 August at the Salzburg Festspielhaus and in Hamburg on 11 November shown until December 31, 1938. From February 1938 to April 1941 it was shown in the following (previously known) cities: Berlin, Leipzig, Dusseldorf, Hamburg, Frankfurt am Main, Vienna, Salzburg, Szczecin and Halle.

The exhibition “Degenerate Art” equated the exhibits with drawings of the mentally handicapped and combined them with photos of crippled people, which were to arouse the visitors with disgust and anxiety. Thus, the concept of art of avant-garde modernism should be reduced to absurdity and modern art understood as “degenerate” and as a decay phenomenon. This presentation of “sick”, ” Jewish-Bolshevik ” art also served to legitimize the persecution of “racially inferior ” and “political opponents”.

Seizure of works of art

Hitler ordered on 24 July 1937 that all museums and public exhibitions had to publish works that were the expression of “cultural decline”. In July 1937, the Reich Chamber of Fine Arts seized z. For example, from the Hamburger Kunsthalle 72 paintings, 296 watercolors, pastels and drawings, 926 etchings, woodcuts and lithographs and eight sculptures. The art collections of the city of Dusseldorf (now Museum Kunstpalast) were withdrawn more than 1000 objects. Some works from this seizure wave were included in the above illustrated traveling exhibition “Degenerate Art”. In further seizure reactions from August 1937, a total of about 20,000 works of art were removed by 1400 artists from over 100 museums. Among them were also loans from private property, such as 13 paintings from the collection of Sophie Lissitzky-Küppers, which were confiscated in the Provincial Museum of Hannover.

Reaction against modernism

The early 20th century was a period of wrenching changes in the arts. In the visual arts, such innovations as Fauvism, Cubism, Dada, and Surrealism—following Symbolism and Post-Impressionism—were not universally appreciated. The majority of people in Germany, as elsewhere, did not care for the new art, which many resented as elitist, morally suspect, and too often incomprehensible. Wilhelm II, who took an active interest in regulating art in Germany, criticized Impressionism as “gutter painting” (Gossenmalerei) and forbade Käthe Kollwitz from being awarded a medal for her print series A Weavers’ Revolt when it was displayed in the Berlin Grand Exhibition of the Arts in 1898. In 1913, the Prussian house of representatives passed a resolution “against degeneracy in art”.

Under the Weimar government of the 1920s, Germany emerged as a leading center of the avant-garde. It was the birthplace of Expressionism in painting and sculpture, of the atonal musical compositions of Arnold Schoenberg, and the jazz-influenced work of Paul Hindemith and Kurt Weill. Films such as Robert Wiene’s The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) and F. W. Murnau’s Nosferatu (1922) brought Expressionism to cinema.

The Nazis viewed the culture of the Weimar period with disgust. Their response stemmed partly from a conservative aesthetic taste and partly from their determination to use culture as a propaganda tool. On both counts, a painting such as Otto Dix’s War Cripples (1920) was anathema to them. It unsparingly depicts four badly disfigured veterans of the First World War, then a familiar sight on Berlin’s streets, rendered in caricatured style. (In 1937, it would be displayed in the Degenerate Art exhibition next to a label accusing Dix—himself a volunteer in World War I—of “an insult to the German heroes of the Great War”.)

In 1930 Wilhelm Frick, a Nazi, became Minister for Culture and Education, and announced a campaign “against Negro culture—for German national traditions”. By his order, 70 mostly Expressionist paintings were removed from the permanent exhibition of the Weimar Schlossmuseum in 1930, and the director of the König Albert Museum in Zwickau, Hildebrand Gurlitt, was dismissed for displaying modern art.

As dictator, Hitler gave his personal taste in art the force of law to a degree never before seen. Only in Stalin’s Soviet Union, where Socialist Realism was the mandatory style, had a modern state shown such concern with regulation of the arts. In the case of Germany, the model was to be classical Greek and Roman art, regarded by Hitler as an art whose exterior form embodied an inner racial ideal.

Art historian Henry Grosshans says that Hitler “saw Greek and Roman art as uncontaminated by Jewish influences. Modern art was [seen as] an act of aesthetic violence by the Jews against the German spirit. Such was true to Hitler even though only Liebermann, Meidner, Freundlich, and Marc Chagall, among those who made significant contributions to the German modernist movement, were Jewish. But Hitler… took upon himself the responsibility of deciding who, in matters of culture, thought and acted like a Jew.”

The supposedly “Jewish” nature of all art that was indecipherable, distorted, or that represented “depraved” subject matter was explained through the concept of degeneracy, which held that distorted and corrupted art was a symptom of an inferior race. By propagating the theory of degeneracy, the Nazis combined their anti-Semitism with their drive to control the culture, thus consolidating public support for both campaigns.

Degeneracy

The term Entartung (or “degeneracy”) had gained currency in Germany by the late 19th century when the critic and author Max Nordau devised the theory presented in his 1892 book Entartung. Nordau drew upon the writings of the criminologist Cesare Lombroso, whose The Criminal Man, published in 1876, attempted to prove that there were “born criminals” whose atavistic personality traits could be detected by scientifically measuring abnormal physical characteristics. Nordau developed from this premise a critique of modern art, explained as the work of those so corrupted and enfeebled by modern life that they have lost the self-control needed to produce coherent works. He attacked Aestheticism in English literature and described the mysticism of the Symbolist movement in French literature as a product of mental pathology. Explaining the painterliness of Impressionism as the sign of a diseased visual cortex, he decried modern degeneracy while praising traditional German culture. Despite the fact that Nordau was Jewish and a key figure in the Zionist movement (Lombroso was also Jewish), his theory of artistic degeneracy would be seized upon by German National Socialists during the Weimar Republic as a rallying point for their anti-Semitic and racist demand for Aryan purity in art.

Belief in a Germanic spirit—defined as mystical, rural, moral, bearing ancient wisdom, and noble in the face of a tragic destiny—existed long before the rise of the Nazis; the composer Richard Wagner celebrated such ideas in his work. Beginning before World War I, the well-known German architect and painter Paul Schultze-Naumburg’s influential writings, which invoked racial theories in condemning modern art and architecture, supplied much of the basis for Adolf Hitler’s belief that classical Greece and the Middle Ages were the true sources of Aryan art. Schultze-Naumburg subsequently wrote such books as Die Kunst der Deutschen. Ihr Wesen und ihre Werke (The art of the Germans. Its nature and its works) and Kunst und Rasse (Art and Race), the latter published in 1928, in which he argued that only racially pure artists could produce a healthy art which upheld timeless ideals of classical beauty, while racially mixed modern artists produced disordered artworks and monstrous depictions of the human form. By reproducing examples of modern art next to photographs of people with deformities and diseases, he graphically reinforced the idea of modernism as a sickness. Alfred Rosenberg developed this theory in Der Mythos des 20. Jahrhunderts (Myth of the Twentieth Century), published in 1933, which became a best-seller in Germany and made Rosenberg the Party’s leading ideological spokesman.

Purge

Hitler’s rise to power on January 31, 1933, was quickly followed by actions intended to cleanse the culture of degeneracy: book burnings were organized, artists and musicians were dismissed from teaching positions, and curators who had shown a partiality to modern art were replaced by Party members. In September 1933, the Reichskulturkammer (Reich Culture Chamber) was established, with Joseph Goebbels, Hitler’s Reichminister für Volksaufklärung und Propaganda (Reich Minister for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda) in charge. Sub-chambers within the Culture Chamber, representing the individual arts (music, film, literature, architecture, and the visual arts) were created; these were membership groups consisting of “racially pure” artists supportive of the Party, or willing to be compliant. Goebbels made it clear: “In future only those who are members of a chamber are allowed to be productive in our cultural life. Membership is open only to those who fulfill the entrance condition. In this way all unwanted and damaging elements have been excluded.” By 1935 the Reich Culture Chamber had 100,000 members.

Nonetheless there was, during the period 1933–1934, some confusion within the Party on the question of Expressionism. Goebbels and some others believed that the forceful works of such artists as Emil Nolde, Ernst Barlach and Erich Heckel exemplified the Nordic spirit; as Goebbels explained, “We National Socialists are not unmodern; we are the carrier of a new modernity, not only in politics and in social matters, but also in art and intellectual matters.” However, a faction led by Alfred Rosenberg despised the Expressionists, and the result was a bitter ideological dispute, which was settled only in September 1934, when Hitler declared that there would be no place for modernist experimentation in the Reich. This edict left many artists initially uncertain as to their status. The work of the Expressionist painter Emil Nolde, a committed member of the Nazi party, continued to be debated even after he was ordered to cease artistic activity in 1936. For many modernist artists, such as Max Beckmann, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, and Oskar Schlemmer, it was not until June 1937 that they surrendered any hope that their work would be tolerated by the authorities.

Although books by Franz Kafka could no longer be bought by 1939, works by ideologically suspect authors such as Hermann Hesse and Hans Fallada were widely read. Mass culture was less stringently regulated than high culture, possibly because the authorities feared the consequences of too heavy-handed interference in popular entertainment. Thus, until the outbreak of the war, most Hollywood films could be screened, including It Happened One Night, San Francisco, and Gone with the Wind. While performance of atonal music was banned, the prohibition of jazz was less strictly enforced. Benny Goodman and Django Reinhardt were popular, and leading British and American jazz bands continued to perform in major cities until the war; thereafter, dance bands officially played “swing” rather than the banned jazz.

Entartete Kunst exhibit

By 1937, the concept of degeneracy was firmly entrenched in Nazi policy. On June 30 of that year Goebbels put Adolf Ziegler, the head of Reichskammer der Bildenden Künste (Reich Chamber of Visual Art), in charge of a six-man commission authorized to confiscate from museums and art collections throughout the Reich, any remaining art deemed modern, degenerate, or subversive. These works were then to be presented to the public in an exhibit intended to incite further revulsion against the “perverse Jewish spirit” penetrating German culture.

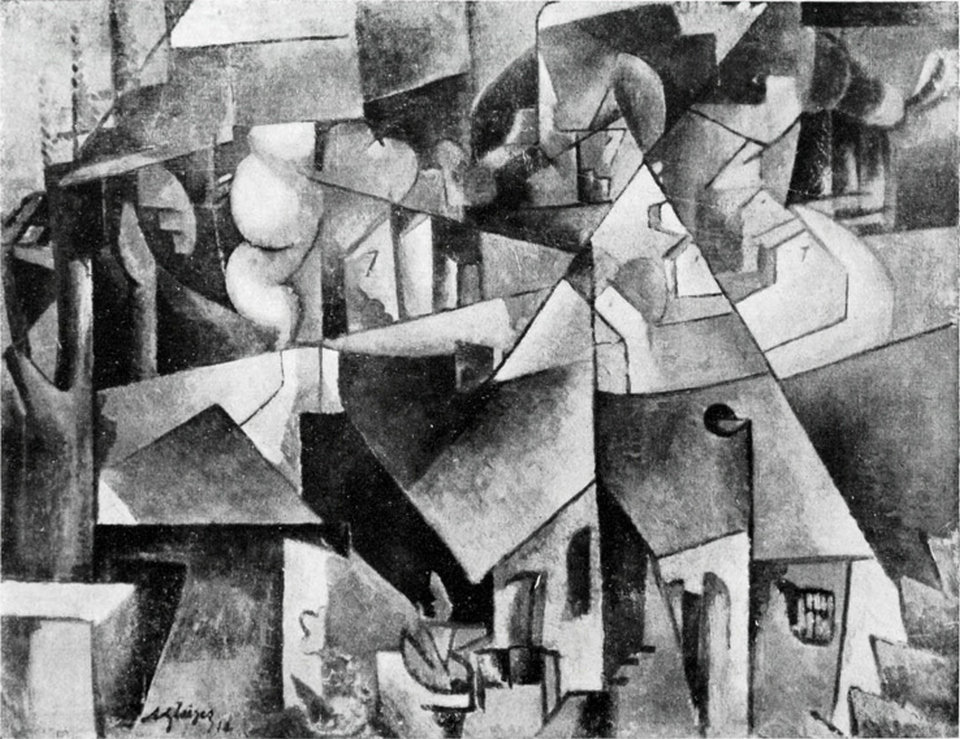

Over 5000 works were seized, including 1052 by Nolde, 759 by Heckel, 639 by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and 508 by Max Beckmann, as well as smaller numbers of works by such artists as Alexander Archipenko, Marc Chagall, James Ensor, Albert Gleizes, Henri Matisse, Jean Metzinger, Pablo Picasso, and Vincent van Gogh. The Entartete Kunst exhibit, featuring over 650 paintings, sculptures, prints, and books from the collections of 32 German museums, premiered in Munich on July 19, 1937, and remained on view until November 30, before traveling to 11 other cities in Germany and Austria.

The exhibit was held on the second floor of a building formerly occupied by the Institute of Archaeology. Viewers had to reach the exhibit by means of a narrow staircase. The first sculpture was an oversized, theatrical portrait of Jesus, which purposely intimidated viewers as they literally bumped into it in order to enter. The rooms were made of temporary partitions and deliberately chaotic and overfilled. Pictures were crowded together, sometimes unframed, usually hung by cord.

The first three rooms were grouped thematically. The first room contained works considered demeaning of religion; the second featured works by Jewish artists in particular; the third contained works deemed insulting to the women, soldiers and farmers of Germany. The rest of the exhibit had no particular theme.

There were slogans painted on the walls. For example:

Insolent mockery of the Divine under Centrist rule

Revelation of the Jewish racial soul

An insult to German womanhood

The ideal—cretin and whore

Deliberate sabotage of national defense

German farmers—a Yiddish view

The Jewish longing for the wilderness reveals itself—in Germany the Negro becomes the racial ideal of a degenerate art

Madness becomes method

Nature as seen by sick minds

Even museum bigwigs called this the “art of the German people”

Speeches of Nazi party leaders contrasted with artist manifestos from various art movements, such as Dada and Surrealism. Next to many paintings were labels indicating how much money a museum spent to acquire the artwork. In the case of paintings acquired during the post-war Weimar hyperinflation of the early 1920s, when the cost of a kilogram loaf of bread reached 233 billion German marks, the prices of the paintings were of course greatly exaggerated. The exhibit was designed to promote the idea that modernism was a conspiracy by people who hated German decency, frequently identified as Jewish-Bolshevist, although only 6 of the 112 artists included in the exhibition were in fact Jewish.

The exhibition program contained photographs of modern artworks accompanied by defamatory text. The cover featured the exhibition title—with the word “Kunst”, meaning art, in scare quotes—superimposed on an image of Otto Freundlich’s sculpture Der Neue Mensch.

A few weeks after the opening of the exhibition, Goebbels ordered a second and more thorough scouring of German art collections; inventory lists indicate that the artworks seized in this second round, combined with those gathered prior to the exhibition, amounted to 16,558 works.

Coinciding with the Entartete Kunst exhibition, the Grosse deutsche Kunstausstellung (Great German art exhibition) made its premiere amid much pageantry. This exhibition, held at the palatial Haus der deutschen Kunst (House of German Art), displayed the work of officially approved artists such as Arno Breker and Adolf Wissel. At the end of four months Entartete Kunst had attracted over two million visitors, nearly three and a half times the number that visited the nearby Grosse deutsche Kunstausstellung.

Fate of the artists and their work

Avant-garde German artists were now branded both enemies of the state and a threat to German culture. Many went into exile. Max Beckmann fled to Amsterdam on the opening day of the Entartete Kunst exhibit. Max Ernst emigrated to America with the assistance of Peggy Guggenheim. Ernst Ludwig Kirchner committed suicide in Switzerland in 1938. Paul Klee spent his years in exile in Switzerland, yet was unable to obtain Swiss citizenship because of his status as a degenerate artist. A leading German dealer, Alfred Flechtheim, died penniless in exile in London in 1937.

Other artists remained in internal exile. Otto Dix retreated to the countryside to paint unpeopled landscapes in a meticulous style that would not provoke the authorities. The Reichskulturkammer forbade artists such as Edgar Ende and Emil Nolde from purchasing painting materials. Those who remained in Germany were forbidden to work at universities and were subject to surprise raids by the Gestapo in order to ensure that they were not violating the ban on producing artwork; Nolde secretly carried on painting, but using only watercolors (so as not to be betrayed by the telltale odor of oil paint). Although officially no artists were put to death because of their work, those of Jewish descent who did not escape from Germany in time were sent to concentration camps. Others were murdered in the Action T4 (see, for example, Elfriede Lohse-Wächtler).

After the exhibit, paintings were sorted out for sale and sold in Switzerland at auction; some pieces were acquired by museums, others by private collectors. Nazi officials took many for their private use: for example, Hermann Göring took 14 valuable pieces, including a Van Gogh and a Cézanne. In March 1939, the Berlin Fire Brigade burned about 4000 paintings, drawings and prints that had apparently little value on the international market. This was an act of unprecedented vandalism, although the Nazis were well used to book burnings on a large scale.

A large amount of “degenerate art” by Picasso, Dalí, Ernst, Klee, Léger and Miró was destroyed in a bonfire on the night of July 27, 1942, in the gardens of the Galerie nationale du Jeu de Paume in Paris. Whereas it was forbidden to export “degenerate art” to Germany, it was still possible to buy and sell artworks of “degenerate artists” in occupied France. The Nazis considered indeed that they should not be concerned by Frenchmen’s mental health. As a consequence, many works made by these artists were sold at the main French auction house during the occupation.

After the collapse of Nazi Germany and the invasion of Berlin by the Red Army, some artwork from the exhibit was found buried underground. It is unclear how many of these then reappeared in the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg, where they still remain.

In 2010, as work began to extend an underground line from Alexanderplatz through the historic city centre to the Brandenburg Gate, a number of sculptures from the degenerate art exhibition were unearthed in the cellar of a private house close to the “Rote Rathaus”. These included, for example, the bronze cubist-style statue of a female dancer by the artist Marg Moll, and are now on display at the Neues Museum.

Listing

The Reichsministerium für Volksaufklärung und Propaganda (Reich Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda) compiled a 479-page, two-volume typewritten listing of the works confiscated as “degenerate” from Germany’s public institutions in 1937–38. In 1996 the Victoria and Albert Museum in London acquired the only known surviving copy of the complete listing. The document was donated to the V&A’s National Art Library by Elfriede Fischer, the widow of the art dealer Heinrich Robert (“Harry”) Fischer. Copies were made available to other libraries and research organisations at the time, and much of the information was subsequently incorporated into a database maintained by the Freie Universität Berlin. A digital reproduction of the entire inventory was published on the Victoria and Albert Museum’s website in January 2014.

The V&A’s version of the inventory is thought to have been compiled in 1941 or 1942, after the sales and disposals were completed. Two copies of an earlier version of Volume 1 (A–G) also survive in the German Federal Archives in Berlin, and one of these is annotated to show the fate of individual artworks. Until the V&A obtained the complete inventory in 1996, all versions of Volume 2 (G–Z) were thought to have been destroyed. The listings are arranged alphabetically by city, museum and artist. Details include artist surname, inventory number, title and medium, followed by a code indicating the fate of the artwork, then the surname of the buyer or art dealer (if any) and any price paid. The entries also include abbreviations to indicate whether the work was included in any of the various Entartete Kunst exhibitions (see Degenerate Art Exhibition) or Der ewige Jude (see The Eternal Jew (art exhibition)).

The main dealers mentioned are Bernhard A. Böhmer (or Boehmer), Karl Buchholz, Hildebrand Gurlitt, and Ferdinand Möller (or Moeller). The manuscript also contains entries for many artworks acquired by the artist Emanuel Fohn, in exchange for other works.

21st-century reactions

Neil Levi, writing in The Chronicle of Higher Education, suggested that the branding of art as “degenerate” was only partly an aesthetic aim of the Nazis. Another was the confiscation of valuable artwork, a deliberate means to enrich the regime.

In popular culture

A Picasso, a play by Jeffrey Hatcher and based loosely inspired by actual events, is set in Paris 1941 and sees Picasso being asked to authenticate three works for inclusion in an upcoming exhibition of Degenerate art.

In the 1954 film The Train, a German Army colonel attempts to steal hundreds of “degenerate” paintings from Paris before it is liberated during World War II.

Source from Wikipedia