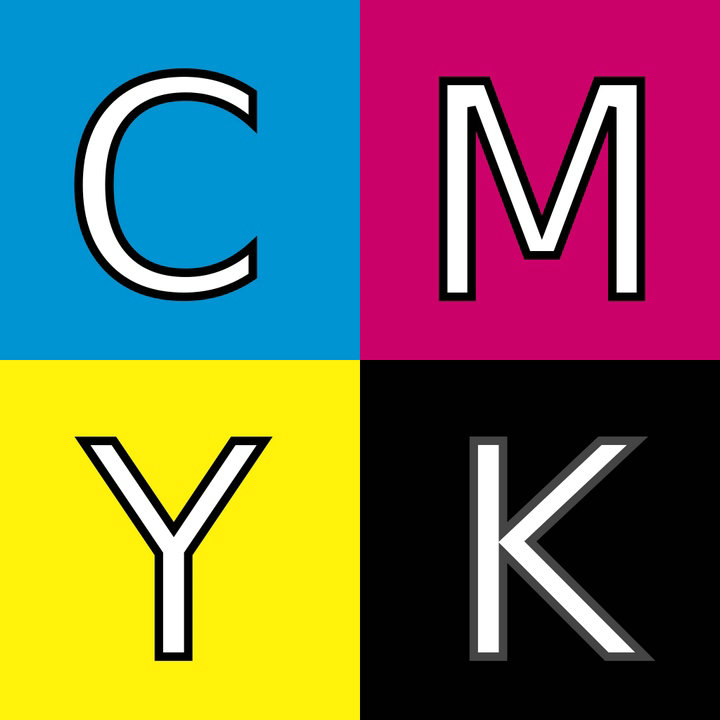

CMYK color model

The CMYK color model (process color, four color) is a subtractive color model, used in color printing, and is also used to describe the printing process itself. CMYK refers to the four inks used in some color printing: cyan, magenta, yellow, and key (black).

The reason for black ink being referred to as key is because in four-color printing, cyan, magenta, and yellow printing plates are carefully keyed, or aligned, with the key of the black key plate. Some sources suggest that the “K” in CMYK comes from the last letter in “black” and was chosen because B already means blue. However, some people disagree with this because there is no blue in the primary CMYK colors; It’s made with cyan and magenta. Some sources claim this explanation, although useful as a mnemonic, is incorrect, that K comes only from “Key” because black is often used as outline and printed first.

The CMYK model works by partially or entirely masking colors on a lighter, usually white, background. The ink reduces the light that would otherwise be reflected. Such a model is called subtractive because inks “subtract” brightness from white.

In additive color models, such as RGB, white is the “additive” combination of all primary colored lights, while black is the absence of light. In the CMYK model, it is the opposite: white is the natural color of the paper or other background, while black results from a full combination of colored inks. To save cost on ink, and to produce deeper black tones, unsaturated and dark colors are produced by using black ink instead of the combination of cyan, magenta, and yellow.

Halftoning

With CMYK printing, halftoning (also called screening) allows for less than full saturation of the primary colors; tiny dots of each primary color are printed in a pattern small enough that humans perceive a solid color. Magenta printed with a 20% halftone, for example, produces a pink color, because the eye perceives the tiny magenta dots on the large white paper as lighter and less saturated than the color of pure magenta ink.

Without halftoning, the three primary process colors could be printed only as solid blocks of color, and therefore could produce only seven colors: the three primaries themselves, plus three secondary colors produced by layering two of the primaries: cyan and yellow produce green, cyan and magenta produce blue, yellow and magenta produce red (these subtractive secondary colors correspond roughly to the additive primary colors), plus layering all three of them resulting in black. With halftoning, a full continuous range of colors can be produced.

Screen angle

To improve print quality and reduce moiré patterns, the screen for each color is set at a different angle. While the angles depend on how many colors are used and the preference of the press operator, typical CMYK process printing uses any of the following screen angles:

C 15° 15° 105° 165°

M 75° 45° 75° 45°

Y 0° 0° 90° 90°

K 45° 75° 15° 105°

Benefits of using black ink

The “black” generated by mixing commercially practical cyan, magenta, and yellow inks is unsatisfactory, so four-color printing uses black ink in addition to the subtractive primaries. Common reasons for using black ink include:

In traditional preparation of color separations, a red keyline on the black line art marked the outline of solid or tint color areas. In some cases a black keyline was used when it served as both a color indicator and an outline to be printed in black. Because usually the black plate contained the keyline, the K in CMYK represents the keyline or black plate, also sometimes called the key plate.

Text is typically printed in black and includes fine detail (such as serifs), so to reproduce text or other finely detailed outlines, without slight blurring, using three inks would require impractically accurate registration.

A combination of 100% cyan, magenta, and yellow inks soaks the paper with ink, making it slower to dry, causing bleeding, or (especially on cheap paper such as newsprint) weakening the paper so much that it tears.

Although a combination of 100% cyan, magenta, and yellow inks should, in theory, completely absorb the entire visible spectrum of light and produce a perfect black, practical inks fall short of their ideal characteristics and the result is actually a dark muddy color that does not quite appear black. Adding black ink absorbs more light and yields much better blacks.

Using black ink is less expensive than using the corresponding amounts of colored inks.

When a very dark area is desirable, a colored or gray CMY “bedding” is applied first, then a full black layer is applied on top, making a rich, deep black; this is called rich black. A black made with just CMY inks is sometimes called a composite black.

The amount of black to use to replace amounts of the other ink is variable, and the choice depends on the technology, paper and ink in use. Processes called under color removal, under color addition, and gray component replacement are used to decide on the final mix; different CMYK recipes will be used depending on the printing task.

Other printer color models

CMYK or process color printing is contrasted with spot color printing, in which specific colored inks are used to generate the colors appearing on paper. Some printing presses are capable of printing with both four-color process inks and additional spot color inks at the same time. High-quality printed materials, such as marketing brochures and books, often include photographs requiring process-color printing, other graphic effects requiring spot colors (such as metallic inks), and finishes such as varnish, which enhances the glossy appearance of the printed piece.

CMYK are the process printers which often have a relatively small color gamut. Processes such as Pantone’s proprietary six-color (CMYKOG) Hexachrome considerably expand the gamut. Light, saturated colors often cannot be created with CMYK, and light colors in general may make visible the halftone pattern. Using a CcMmYK process, with the addition of light cyan and magenta inks to CMYK, can solve these problems, and such a process is used by many inkjet printers, including desktop models.

Comparison with RGB displays

Comparisons between RGB displays and CMYK prints can be difficult, since the color reproduction technologies and properties are very different. A computer monitor mixes shades of red, green, and blue light to create color pictures. A CMYK printer instead uses light-absorbing cyan, magenta, and yellow inks, whose colors are mixed using dithering, halftoning, or some other optical technique.

Similar to monitors, the inks used in printing produce a color gamut that is “only a subset of the visible spectrum” although both color modes have their own specific ranges. As a result of this items which are displayed on a computer monitor may not completely match the look of items which are printed if opposite color modes are being combined in both mediums. When designing items to be printed, designers view the colors which they are choosing on an RGB color mode (their computer screen), and it is often difficult to visualize the way in which the color will turn out post-printing because of this.

Spectrum of Printed Paper

To reproduce color, the CMYK color model codes for absorbing light rather than emitting it (as is assumed by RGB). The ‘K’ component absorbs all wavelengths and is therefore achromatic. The Cyan, Magenta, and Yellow components are used for color reproduction and they may be viewed as the inverse of RGB. Cyan absorbs Red, Magenta absorbs Green, and Yellow absorbs Blue (-R,-G,-B).

Conversion

Since RGB and CMYK spaces are both device-dependent spaces, there is no simple or general conversion formula that converts between them. Conversions are generally done through color management systems, using color profiles that describe the spaces being converted. Nevertheless, the conversions cannot be exact, particularly where these spaces have different gamuts.

The problem of computing a colorimetric estimate of the color that results from printing various combinations of ink has been addressed by many scientists. A general method that has emerged for the case of halftone printing is to treat each tiny overlap of color dots as one of 8 (combinations of CMY) or of 16 (combinations of CMYK) colors, which in this context are known as Neugebauer primaries. The resultant color would be an area-weighted colorimetric combination of these primary colors, except that the Yule–Nielsen effect (“dot gain”) of scattered light between and within the areas complicates the physics and the analysis; empirical formulas for such analysis have been developed, in terms of detailed dye combination absorption spectra and empirical parameters.

Conversion between RGB and CMYK

To convert between RGB and CMYK, an intermediate CMY value is used. The color values are represented as a vector, each of them being able to vary between 0.0 (non-existent color) and 1.0 (totally saturated color):

Conversion CMYK to RGB

To achieve the conversion, it is first passed from CMYK to CMY, and later to RGB.

Mapping from RGB to CMYK

You can map an RGB color given to one of the many semi-equivalent CMYK colors possible. The best option is the one that uses K as much as possible, and the remaining CMY proportions as little as possible. For example, # 808080 (gray, the exact half between black and white) will be mapped to (0,0,0,0.5) and not to (0.5,0,5,0,5,0).

Converting RGB → CMY, with the same color vectors:

turning to CMY

and then to CMYK:

if

so

else

Source From Wikipedia