The Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Op. 125, also known as Beethoven’s 9th, is the final complete symphony by Ludwig van Beethoven, composed between 1822 and 1824. It was first performed in Vienna on 7 May 1824. One of the best-known works in common practice music, it is regarded by many critics and musicologists as one of Beethoven’s greatest works and one of the supreme achievements in the history of western music. In the 2010s, it stands as one of the most performed symphonies in the world.

The symphony was the first example of a major composer using voices in a symphony (thus making it a choral symphony). The words are sung during the final (4th) movement of the symphony by four vocal soloists and a chorus. They were taken from the “Ode to Joy”, a poem written by Friedrich Schiller in 1785 and revised in 1803, with text additions made by Beethoven.

In 2001, Beethoven’s original, hand-written manuscript of the score, held by the Berlin State Library, was added to the United Nations Memory of the World Programme Heritage list, becoming the first musical score so designated.

Composition

The Philharmonic Society of London originally commissioned the symphony in 1817. The main composition work was done between autumn 1822 and the completion of the autograph in February 1824. The symphony emerged from other pieces by Beethoven that, while completed works in their own right, are also in some sense “sketches” (rough outlines) for the future symphony. The Choral Fantasy Opus. 80 (1808), basically a piano concerto movement, brings in a choir and vocal soloists near the end for the climax. The vocal forces sing a theme first played instrumentally, and this theme is reminiscent of the corresponding theme in the Ninth Symphony (for a detailed comparison, see Choral Fantasy).

Going further back, an earlier version of the Choral Fantasy theme is found in the song “Gegenliebe” (Returned Love) for piano and high voice, which dates from before 1795. According to Robert W. Gutman, Mozart’s K. 222 Offertory in D minor, “Misericordias Domini”, written in 1775, contains a melody that foreshadows “Ode to Joy”.

Premiere

Although his major works had primarily been premiered in Vienna, Beethoven was keen to have his latest composition performed in Berlin as soon as possible after finishing it, as he thought that musical taste in Vienna had become dominated by Italian composers such as Rossini. When his friends and financiers heard this, they urged him to premiere the symphony in Vienna in the form of a petition signed by a number of prominent Viennese music patrons and performers.

Beethoven was flattered by the adoration of Vienna, so the Ninth Symphony was premiered on 7 May 1824 in the Theater am Kärntnertor in Vienna along with the overture The Consecration of the House (Die Weihe des Hauses) and three parts of the Missa solemnis (the Kyrie, Credo, and Agnus Dei). This was the composer’s first onstage appearance in 12 years; the hall was packed with an eager audience and a number of musicians.

The premiere of Symphony No. 9 involved the largest orchestra ever assembled by Beethoven and required the combined efforts of the Kärntnertor house orchestra, the Vienna Music Society (Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde), and a select group of capable amateurs. While no complete list of premiere performers exists, many of Vienna’s most elite performers are known to have participated.

The soprano and alto parts were sung by two famous young singers: Henriette Sontag and Caroline Unger. German soprano Henriette Sontag was 18 years old when Beethoven personally recruited her to perform in the premiere of the Ninth. Also personally recruited by Beethoven, 20-year-old contralto Caroline Unger, a native of Vienna, had gained critical praise in 1821 appearing in Rossini’s Tancredi. After performing in Beethoven’s 1824 premiere, Unger then found fame in Italy and Paris. Italian composers Donizetti and Bellini were known to have written roles specifically for her voice. Anton Haizinger and Joseph Seipelt sang the tenor and bass/baritone parts, respectively.

Although the performance was officially directed by Michael Umlauf, the theatre’s Kapellmeister, Beethoven shared the stage with him. However, two years earlier, Umlauf had watched as the composer’s attempt to conduct a dress rehearsal of his opera Fidelio ended in disaster. So this time, he instructed the singers and musicians to ignore the almost totally deaf Beethoven. At the beginning of every part, Beethoven, who sat by the stage, gave the tempos. He was turning the pages of his score and beating time for an orchestra he could not hear.

There are a number of anecdotes about the premiere of the Ninth. Based on the testimony of the participants, there are suggestions that it was underrehearsed (there were only two full rehearsals) and rather scrappy in execution. On the other hand, the premiere was a great success. In any case, Beethoven was not to blame, as violinist Joseph Böhm recalled:

Beethoven himself conducted, that is, he stood in front of a conductor’s stand and threw himself back and forth like a madman. At one moment he stretched to his full height, at the next he crouched down to the floor, he flailed about with his hands and feet as though he wanted to play all the instruments and sing all the chorus parts.—The actual direction was in Duport’s hands; we musicians followed his baton only.

When the audience applauded—testimonies differ over whether at the end of the scherzo or symphony—Beethoven was several measures off and still conducting. Because of that, the contralto Caroline Unger walked over and turned Beethoven around to accept the audience’s cheers and applause. According to the critic for the Theater-Zeitung, “the public received the musical hero with the utmost respect and sympathy, listened to his wonderful, gigantic creations with the most absorbed attention and broke out in jubilant applause, often during sections, and repeatedly at the end of them.” The audience acclaimed him through standing ovations five times; there were handkerchiefs in the air, hats, and raised hands, so that Beethoven, who could not hear the applause, could at least see the ovations.

Analysis of the individual sentences

The length of the fourth movement threatened to lose the balance between the sentences. Beethoven counteracts this by putting the usually second slow movement on the third position. The third movement thus acts as a resting center in the complete work.

First sentence

(Allegro ma non troppo, un poco maestoso, d minor)

The first movement of the Ninth Symphony corresponds to the sonata form with a relatively short reprise and oversized coda. The sentence comprises almost 600 bars. The first theme is preceded by an introduction, which does not begin in D minor, but in A. (Tong not set, because third is missing = a so-called ” empty fifth” ). Thus, this A turns out to be dominant to the main key of D minor and in bar 17 the main theme (chord breaks in D minor) begins in dotted rhythm. After a divergence to E flat major, the music returns to its calm and the introduction is also preceded by the aftermath, this time in d. The trailer is already in the sub-medianB major (as usual in Romanticism) and in bar 80, the transition (with its own theme) to the second complex of themes, the page set in B major, begins. The pagination brings three themes, one lyrical and two more martial themes. After this page follows a two-part final group ending in B flat major. The performance also begins with the introduction, again on A, it is divided into four sections, the third section is a large double furato. The reprise has no suffix and remains largely in D minor (or major). The coda no longer leaves the tonic and contains a new, mourn-like theme. The sentence ends in unison (Akkordbrechung d minor).

The first movement of Ludwig van Beethoven’s 9th Symphony, Allegro ma non troppo, un poco maestoso, is perceived by the listener as powerful and harsh. The main clause begins with an introduction, a crescendo that later appears repeatedly in this sentence. With the increase in volume, the rhythm also increases, it “becomes narrower” and strengthens the power and the fear that have formed with the crescendo. The theme, beginning in bar 17, which is now played in Fortissimo, seems to have come from nothing; However, this is a fallacy, in the introduction, it has already been suggested, but now the note values are greatly shortened, which is why now only one topic can be seen. His drama is enhanced by playing in tutti. The end of the theme is characterized by “martial rhythms in trumpets and timpani”, the woodwind play in contrast to quiet motifs. It ends and followed by a short transition to the motif of the introduction or the main clause, which is followed a second time by the theme.

The final motif, consisting of hectic sixteenth movements, will continue at this point for a very long time. It is followed by the last movement, whose half sentence takes a gentler end. Fourfold there is a fine motif in the woodwinds (dolce); This is the transition to the new tonic B major made, with her starts the page set. The themes of the antecedent clearly determine the woodwinds, which are accompanied by the violins, among others, with a varied motif section of the first theme. The epilogue does not follow directly, the piece is interrupted by a motif, the epilogue leads over. He then seems to be coming to an end, Beethoven, however, is adding another, more highly developed epilogue to this. Here he repeatedly uses the motifs of the first theme, tearing the movement out of its harmony until the winds begin with a slight cadence in the direction of B major, but arrive at B flat major. This is followed by the long way back to Tonika B-Dur. Both parts, main clause and pagination, “do not evolve linearly, not ‘organically'”, but they are nevertheless so opposite to each other, they represent “different worlds: the inner and the outer world”. The main theorem, the outer world that is threatening and powerful against the listener, and the inner world that reflects the listener’s sense of identification.

The following execution is from the beginning further in the direction of reprise. The first part is dominated by the motifs of the initial crescendo and the first theme. This is followed by a fugato, the second part of the performance in which the chaos that has formed during the cadenza is dissolved. At this point the way to the recapitulation is already very clear. The execution ends. However, she seems to have reached her final climax here as well.

The subsequent recapitulation is the central point of the first movement, it begins in Fortissimo, supported by the “rolling thunder” of the timpani. This is of such eerie beauty and so threatening that it overshadows all the horrors and anxieties that have built up before. This does not increase any further in the following, the tension is rather reduced again a bit and seems to have arrived at a constant level to be always present. The other parts of the reprise are in the shadow of this powerful beginning.

The coda is there a contrast. Described as “sweet”, she stands out from the overall picture of the reprise and initiates the end. It increases and reduces this increase again, here begins the first major crescendo, followed by another crescendo, which drives the sentence once more. After this, the old tempo is resumed, followed by a quiet part, which is quiet, but at the same time dramatic and intensifying. This is continued, the increase is maintained by the change from the piano via forte to fortissimo. The last bars of the movement are closed with mournful rhythms.

Second sentence

(Molto vivace – Presto, D minor)

The second movement of the symphony is a scherzo and trio. Formally, it is laid out in the usual shape scheme A – B – A, whereby the two parts of the scherzo are repeated in the first round (A1 – A1 – A2 – A2 – B – A1 – A2). In some performances, however, renounced the repetitions within the Scherzo.

Scherzo

As usual, the Scherzo is recorded in 3/4 time. The auditory impression, however, is a 4/4 time, as the high tempo of the piece, the bars act as basic strokes and are arranged musically in groups of four bars. This can be understood as an ironic sideline against critics who held Beethoven in disregard of musical traditions.

Beethoven opens the second movement with a short opening. This consists of a one-bar motif, formed from an octave jump played by the strings. This is interrupted by a general pause, then it is repeated sequenced. It is followed by another general pause, then the motif, played in a flash and thunder by the timpani, which are imitated by the almost complete orchestra in the following measure. Thus, within two bars, the timpani and the entire orchestra face each other with all their might and fullness. Allegedly, at the premiere after this surprising general pause spontaneous applause set in, which forced the orchestra to start the sentence again.

After another general break, the actual main movement, the first theme, begins based on the theme of the introduction. After the type of fugue, the theme sets all four bars in a new string voice. The use of the winds completes the orchestra as a tutti. This is followed by a long, extended crescendo, now the theme is played in fortissimo by the entire orchestra. The timpani also start again, they finally complete the orchestra and underline the striking motif and its rhythm. After this first climax of the movement descending lines of the woodwind give a brief respite, until in the fortissimo an energetic side theme begins. The winds and timpani are accompanied by the strings, which use the one-bar entry motif as a driving ostinato.

The second form part has some structural parallels to the first part: After a short transition, it begins again with the fugal processing of the main theme. This time, however, it is the woodwind voices that use one after the other. In contrast to the first part of the insert is not every four bars, but every third bar. The “Metataktart” changes for a time to a three-beat, which is characterized by the game instruction Ritmo di tre battute (rhythm to three strokes). There follows an extensive increase. After their culmination resound as in the first part of the descending brass lines, to be replaced by the side theme in Fortissimo.

Trio

The transition to the trio (D major, 2/2-Takt) takes place without interruption, the tempo increases in the previous bars continuously in the Presto. The theme of the trio, in contrast to the Scherzo, has a very cantabile character. It is first presented together by oboes and clarinets. Horns and bassoons take over the solo part one after the other. Then the strings pick up the theme together with the woodwinds. After the repetition of this section, it finally reappears in the deep strings.

Coda

The coda follows the da-capo of the scherzo, in which the main theme of the scherzo is fugally condensed into a voice after every 2 bars. Then the lovely theme of the trio sounds again. However, it is not played out in full length, but abruptly aborted two bars before the end of the phrase. After a pause, there follows a chain of defiant octave jumps, ending the second movement. These are at the same time a break between the scherzo and the following third movement, which starts once more from the very beginning with its new, much quieter tempo.

Third sentence

(Adagio molto e cantabile – Andante moderato, Bb major)

In the third movement Beethoven has the instruments inserted one after the other. So the second bassoon starts alone, followed by the first bassoon, the second clarinet, the strings (except the first violin and double bass) and the first clarinet. These begin directly in succession, the theme then begins in the first violin. After the first sounding of the complete theme, the horns begin to take over the motifs together with the clarinet. For the time being, it will only be imitated with short inserts in the first bars and in the further course the clarinet has completely taken over the theme, the strings now take over the accompaniment.

At this point, Beethoven changes to D major a new form part, an intermediate movement, is introduced (Andante moderato) and stands out from the previous part by a change of measure (¾) and a faster tempo. The mood is maintained because the statement of both parts is similar and the cantabile is maintained. Again, the first violin takes over the theme tour and is accompanied by the rest of the strings and the woodwinds.

The theme of the interlude is played twice. This is followed by the transition to the previous B major key and the return to the old tempo. Now the first theme sounds in a variation, the first violin plays around it with a playful sixteenth movement, interrupted by individual interjections of the theme by the woodwinds. In the following bars, the transition to G major begins. Here begins a second interlude (Andante), in which again the woodwinds, primarily the flutes and bassoons, the second theme varies play.

The now beginning return to the main part, here in E-flat major (Adagio) is determined by a second variation on the first theme, a free-form variation of the horns and flutes. This seems to have got out of step, the accompaniment of the strings seems to have shifted the rhythm. This is remedied by a sixteenth note of the horns, here begins the introduction to A major, the Coda, in which the first violin plays the third variation, which consists repeatedly of sixteenth movements. In part, these seem to be picking up the pace; this effect comes from triplets and thirty-second notes. These are interrupted by a fanfare, initiated by the horns. This breaks through the mood and the rest, which is immediately restored by calming acting chords. Here again the third variation of the first violins, is interrupted again by the fanfare.

This is followed by a very cantabile passage, which releases the mood from the hard, almost cruel, fanfare and sounds joyful in its approach, which are repeatedly processed in the following bars. The third variation of the first violin can also be heard repeatedly.

The third movement ends with several crescendos followed by a short piano. This seems depressing; it underlines the prevailing gloomy mood of previous phrases. This last fanfare seems to arouse the listener one last time, it works the same way as an announcement for the important following statement of the last sentence.

Fourth sentence

Allegro energico, semper ben marcato – Allegro ma non tanto – Prestissimo, D minor / D major)

In the fourth movement, a quartet of singers and a large four-part choir perform the stanzas of the poem To the Joy of Friedrich Schiller. They are musically equal to the orchestra. The melody of the main theme is accompanied by the text passage “Joy, beautiful divine spark (…)”. This phrase is therefore also called the “Ode to Joy”.

Beethoven introduces the fourth movement of his Ninth Symphony, which at 940 bars is not only long but also overwhelming, with some dissonances of the winds that reflect the rage and desperation of the preceding movements, perhaps even pain. Only gradually do the string basses seem to tackle it, they pave the way for something completely new, through a slow, calm motive, a new idea for the further course of the piece. This is constantly interrupted by the themes of the first three movements, beginning with the first theme of the first movement. At this point, the basses choke on the old idea, but now the introduction to the first movement follows.

Again, the string basses destroy the old motif by their interruption; This is followed by a section of the first theme of the second movement in Vivace. The basses repeatedly revolt and the use of the first motif of the first theme of the third movement is also discarded. But at this point, the woodwinds bring the new idea for the first time, which the basses seem to agree with. The new thought is not rejected, but taken up by the basses, only pursued recitatively and is then – the first time in the piece – to hear completely with the joyful melody “joy, beautiful divine spark”, played by the previously restless string basses. It is presented as a thrice eight-bar theme.

At first only bassoon and viola join in the song of joy; but in the course of the following bars there is an increase, not only in terms of the voltage curve, but also in relation to the number of instruments involved. Thus, the impact of other instruments such as the accumulation of a crowd that sings in the jubilee choir, with an enormous arc of suspense, the happiness of the world.

At this point, the melody no longer sounds as timid and veiled as before, but majestically and magnificently, which is underlined by timpani and brass. But after the theme has wandered through the individual voices, everything falls back into the uncontrolled confusion, which ends in violent dissonance in a greater chaos than the one that prevailed at the beginning, emphasized by the well-known thunder rumble of the timpani. Only when using the baritone solos “O friends, not these sounds! But let us sing more pleasant, and more joyful, ” which is at the same time the actual beginning of the main part of the movement, the song of joy is announced, which, arrived in the actual key of D major, is initiated by “joy ” – reproaches of the bass voice of the choir and for the time being only recited by the baritone soloist and only afterwards by the choir and later also by the soloists is sung. It is striking here that the soprano suspends for the time being and only at the point “who won a fair wife” uses.

The orchestra continues to accompany the singers with suggestions and variations of the new theme. Now, as a soloist choir and choir, they sing the individual verses, apparently very important to Beethoven, of Schiller’s poem “To the Joy”. Here, too, the orchestra stays rather small at the auditions of the soloists, followed by a larger and stronger line-up for the choir, which together result in a more splendid picture. Even within the individual vocal parts, the voices are fugal. The first part of the finale ends with the line “and the cherub stands before God”, which is sung repeatedly by the choir and sounds very lofty and mighty, not least because of the soprano voice, which is here on a long two-pointed a ends.

Now follows the joyful theme in march-like rhythm (Alla Marcia), which is caused not only by the change of the meter, but also by the first use of three percussion instruments (triangle, bass drum and pelvis). The tenor soloist begins with the next passage of the text with an appropriate rhythm of the vocal melody, which repeats the male voices of the choir with wild, combative character. Here begins a march-like interlude, followed by another chorus. Here – with the text of the first stanza and keeping the march character – the end of this section is initiated.

The following Andante maestoso, with the new central statement “Brothers! A dear father must dwell above the star-tipped tent. “Has a heavy, sacral character, which can be explained by referring to the” Creator “, to God. Even the fortissimo of these lines expresses the importance of the text for Beethoven. They form the climax of the choral finale, which at first sounds very powerful through the unison of male voices, then sounds exultant and overwhelming through the use of women’s voices. Beginning with the male voices and the accompaniment of the bass trombone and the string basses in unison, this powerful person looks very dark, which becomes a magical obscuring of the theme of joy through the incessant female voices. These following imitations amplify the polyphony of this passage, The almost complete orchestra makes everything seem even bigger and more powerful than before. The special weight on the spot “over the star tent” by singing twice on just one note and anti-meter rhythms are reinforced by the non-melodization of “Are you the creator, world?”, Which describes the mystical unavailability of God. When the words “above the star-tent must he dwells” sound again for the third time – again on a note – the effect of far distance arises, since the flutes and violins mimic the starry sparkle, the sound being slender, yet full.

Now follows the fourth part of the fourth movement, which is doublefounded. He combines the theme of joy and the sacred motif, which is a link between heaven (sacral motif: “above the star’s tent must dwell a dear father”) and earth (joy theme: “all men become brothers”). The fugue builds tremendous power and energy, and here, as at the end of the first part of the finale, it finds its climax and its end on the two-pointed a of the soprano parts. This comes suddenly, the fugue and thus the euphoria are broken off. It begins a hesitant questions, only in the basses “you fall down, millions?”, Followed by the tenors “do you suspect the creator, world?”, Answered by the old: “search him over the star-tent”. This passage is now being repeatedly edited, she concludes the end of the fourth part of the finale. Here again, Beethoven places more value on the statement of the text than on the melody of it.

The following fifth part begins in pianissimo with a distant variation of the theme of joy, the incipient soloists sing once more the first verse of “To the Joy”, but here in a new setting. The male voices begin as before, the female voices begin; this fugato now takes place in the change of the two parties. This new motif will be recorded by the choir. In the first inserted Adagio, the following line of text, “All men become brothers, where thy gentle wing dwells,” is emphasized by the choir. However, this insertion takes only four bars; afterwards Beethoven returns to the original tempo. After a short fugato between choir and soloists, a second adagio insert takes place, in which the important passage for Beethoven “all men become brothers” is emphasized once again, but not by the choir, but by the soloists,

In the last part of the fourth movement of the Ninth Symphony, a Prestissimo, Beethoven repeatedly uses the percussion instruments to underline the exuberance (timpani, bass drum, cymbals, triangle). In the extremely fast meter of this last part, the sacred motif (bar 5) that appears there can only be recognized by the notation, because of the faster rhythms it has completely changed its character. Until the Maestoso the text “Be embraced, millions; This kiss for the whole world! Brothers! Over the star tent, a dear father must live “from a new point of view. Here, too, Beethoven wants to make room for something new by presenting it differently than before.

The subsequent Maestoso, on the other hand, is a rather slow, pacing insertion in the hectic, almost elusive Prestissimo. Here again Beethoven takes up the first line of the first stanza and announces the end of the last movement, the final finale, in which the “joy”, the “beautiful divine spark”, revives for the last time at the same time as the last thought concludes the song. The orchestra manifests the great joy over another 20 bars in the Prestissimo and lets the symphony end in jubilation.

Instrumentation

The symphony is scored for the following orchestra. These are by far the largest forces needed for any Beethoven symphony; at the premiere, Beethoven augmented them further by assigning two players to each wind part.

Woodwinds

Piccolo (fourth movement only)

2 Flutes

2 Oboes

2 Clarinets in A, B♭ and C

2 Bassoons

Contrabassoon (fourth movement only)

Brass

4 Horns in D, B♭ and E♭

2 Trumpets in D and B♭

3 Trombones (alto, tenor, and bass; second and fourth movements only)

Percussion

Timpani

Bass drum (fourth movement only)

Triangle (fourth movement only)

Cymbals (fourth movement only)

Voices (fourth movement only)

Soprano solo

Alto solo

Tenor solo

Baritone (or bass) solo

SATB choir (tenor briefly divides)

Strings

Violins I, II

Violas

Cellos

Double basses

Text of the fourth movement

The text is largely taken from Friedrich Schiller’s “Ode to Joy”, with a few additional introductory words written specifically by Beethoven (shown in italics). The text, without repeats, is shown below, with a translation into English.

Oh friends, not these sounds!

Let us instead strike up more pleasing

and more joyful ones!

Joy!

Joy!

Joy, beautiful spark of divinity,

Daughter from Elysium,

We enter, burning with fervour,

heavenly being, your sanctuary!

Your magic brings together

what custom has sternly divided.

All men shall become brothers,

wherever your gentle wings hover.

Whoever has been lucky enough

to become a friend to a friend,

Whoever has found a beloved wife,

let him join our songs of praise!

Yes, and anyone who can call one soul

his own on this earth!

Any who cannot, let them slink away

from this gathering in tears!

Every creature drinks in joy

at nature’s breast;

Good and Evil alike

follow her trail of roses.

She gives us kisses and wine,

a true friend, even in death;

Even the worm was given desire,

and the cherub stands before God.

Gladly, just as His suns hurtle

through the glorious universe,

So you, brothers, should run your course,

joyfully, like a conquering hero.

Be embraced, you millions!

This kiss is for the whole world!

Brothers, above the canopy of stars

must dwell a loving father.

Do you bow down before Him, you millions?

Do you sense your Creator, O world?

Seek Him above the canopy of stars!

He must dwell beyond the stars.

Towards the end of the movement, the choir sings the last four lines of the main theme, concluding with “Alle Menschen” before the soloists sing for one last time the song of joy at a slower tempo. The chorus repeats parts of “Seid umschlungen, Millionen!”, then quietly sings, “Tochter aus Elysium”, and finally, “Freude, schöner Götterfunken, Götterfunken!”.

Reception

Music critics almost universally consider the Ninth Symphony one of Beethoven’s greatest works, and among the greatest musical works ever written. The finale, however, has had its detractors: “arly critics rejected [the finale] as cryptic and eccentric, the product of a deaf and aging composer.” Verdi admired the first three movements but lamented the confused structure and the bad writing for the voices in the last movement:

The alpha and omega is Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, marvelous in the first three movements, very badly set in the last. No one will ever approach the sublimity of the first movement, but it will be an easy task to write as badly for voices as in the last movement. And supported by the authority of Beethoven, they will all shout: “That’s the way to do it…

— Giuseppe Verdi, 1878

Giuseppe Verdi complained that the final was “bad set”. Richard Wagner said, “The Ninth is salvation of music from its very own element to general art. It is the human gospel of the art of the future. ”

In Germany, France, and England, there was no shortage of derogatory judgments, occasionally combined with benevolent advice to the composer. Many turned sharply against the use of voices in a symphony.

Even in later times, there were different opinions: “The 9th Symphony is a key work of symphonic music” and has inspired many subsequent musicians, eg. As Anton Bruckner, Gustav Mahler, Johannes Brahms. In contrast to such positive statements, Thomas Beecham stated that “even if Beethoven had tapped well into the strings, the Ninth Symphony was composed by some sort of Mr. Gladstone of music.”

Influence

Many later composers of the Romantic period and beyond were influenced by the Ninth Symphony.

An important theme in the finale of Johannes Brahms’ Symphony No. 1 in C minor is related to the “Ode to Joy” theme from the last movement of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. When this was pointed out to Brahms, he is reputed to have retorted “Any fool can see that!” Brahms’s first symphony was, at times, both praised and derided as “Beethoven’s Tenth”.

The Ninth Symphony influenced the forms that Anton Bruckner used for the movements of his symphonies. His Symphony No. 3 is in the same D-minor key as Beethoven’s 9th and makes substantial use of thematic ideas from it. The colossal slow movement of Bruckner’s Symphony No. 7, “as usual”, takes the same A–B–A–B–A form as the 3rd movement of Beethoven’s symphony and also uses some figuration from it.

In the opening notes of the third movement of his Symphony No. 9 (From the New World), Antonín Dvořák pays homage to the scherzo of this symphony with his falling fourths and timpani strokes.

Likewise, Béla Bartók borrows the opening motif of the scherzo from Beethoven’s Ninth symphony to introduce the second movement scherzo in his own Four Orchestral Pieces, Op. 12 (Sz 51).

One legend is that the compact disc was deliberately designed to have a 74-minute playing time so that it could accommodate Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. Kees Immink, Philips’ chief engineer, who developed the CD, recalls that a commercial tug-of-war between the development partners, Sony and Philips, led to a settlement in a neutral 12-cm diameter format. The 1951 performance of the Ninth Symphony conducted by Furtwängler was brought forward as the perfect excuse for the change, and was put forth in a Philips news release celebrating the 25th anniversary of the Compact Disc as the reason for the 74-minute length.

In the film The Pervert’s Guide to Ideology, the psychoanalytical Communist philosopher Slavoj Žižek comments on the use of the Ode by Nazism, Bolshevism, the Chinese Cultural Revolution, the East-West German Olympic team, Southern Rhodesia, Abimael Guzmán (leader of the Shining Path), and the Council of Europe and the European Union.

Use as (national) anthem

During the division of Germany in the Cold War, the “Ode to Joy” segment of the symphony was played in lieu of an anthem at the Olympic Games for the United Team of Germany between 1956 and 1968. In 1972, the musical backing (without the words) was adopted as the Anthem of Europe by the Council of Europe and subsequently by the European Communities (now the European Union) in 1985. The “Ode to Joy” was used as the national anthem of Rhodesia between 1974 and 1979, as “Rise, O Voices of Rhodesia”.

Use as a hymn melody

In 1907, the Presbyterian pastor Henry van Dyke wrote the hymn “Joyful, Joyful, we adore thee” while staying at Williams College. The hymn is commonly sung in English-language churches to the “Ode to Joy” melody from this symphony.

Year-end tradition

The German workers’ movement began the tradition of performing the Ninth Symphony on New Year’s Eve in 1918. Performances started at 11pm so that the symphony’s finale would be played at the beginning of the new year. This tradition continued during the Nazi period and was also observed by East Germany after the war.

The Ninth Symphony is traditionally performed throughout Japan at the end of the year. In December 2009, for example, there were 55 performances of the symphony by various major orchestras and choirs in Japan.

It was introduced to Japan during World War I by German prisoners held at the Bandō prisoner-of-war camp. Japanese orchestras, notably the NHK Symphony Orchestra, began performing the symphony in 1925 and during World War II, the Imperial government promoted performances of the symphony, including on New Year’s Eve. In an effort to capitalize on its popularity, orchestras and choruses undergoing economic hard times during Japan’s reconstruction, performed the piece at year’s end. In the 1960s, these year-end performances of the symphony became more widespread, and included the participation of local choirs and orchestras, firmly establishing a tradition that continues today.

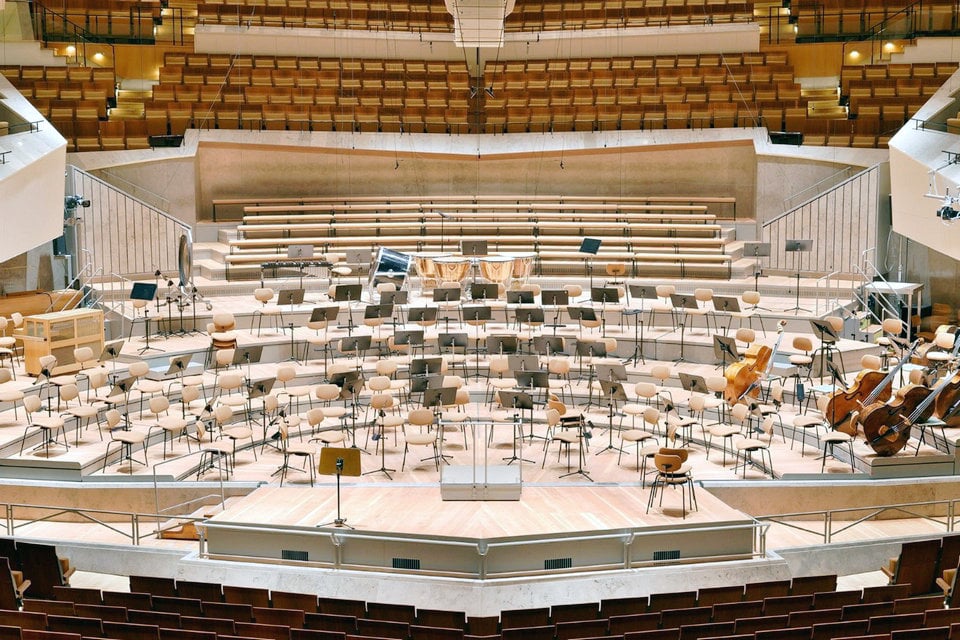

Berlin Philharmonic

The Berlin Philharmonic is a German orchestra based in Berlin. It is traditionally ranked in the top handful of orchestras in the world, distinguished amongst peers for its virtuosity and compelling sound. The orchestra’s history has always been tied to its chief conductors, many of whom have been authoritative and controversial characters, such as Wilhelm Furtwängler and Herbert von Karajan.

The Berlin Philharmonic, founded in 1882, is considered to be one of the best orchestras in the world. Famous conductors like Wilhelm Furtwängler, Herbert von Karajan and Claudio Abbado heavily influenced the orchestra’s history and development. In 2002, Sir Simon Rattle took over as conductor. During his leadership, the orchestra was able to engage new audiences through its Education Program. The program is funded through generous contributions by the Deutsche Bank. In 2009, the Berlin Philharmonic started a new, innovative project: the Digital Concert Hall, which presents the Philharmonic’s live concerts on the web. The Berlin Philharmonic building is home to the orchestra. Built by Hans Scharoun, its groundbreaking architecture serves as a model for concert halls across the world.