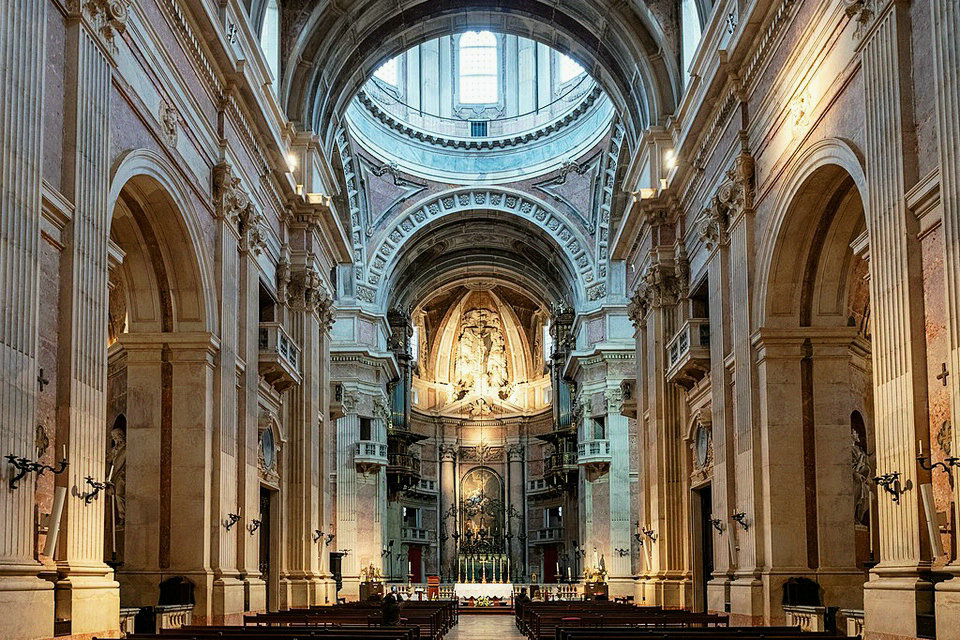

The church is built in the form of a Latin cross with a length of 63 m. It is rather narrow (16.5 m), an impression accentuated by the height of its nave (21.5 m). The vestibule (Galilee porch) contains a group of large sculptures in Carrara marble, representing the patron saints of several monastic orders.

The interior makes abundantly use of local rose-coloured marble, intermingled with white marble in different patterns. The multi-coloured designs of the floor are repeated on the ceiling. The barrel vault rests on fluted Corinthian semicolumns standing between the side chapels. The chapels in the transept contain altarpieces in jasper made by sculptors from the School of Mafra. The side aisles display 58 marble statues commissioned from the best Roman sculptors of their time. The All Saint’s chapel in the transept is screened from the crossing by iron railings with bronze ornaments, made in Antwerp.

The choir has a magnificent giant candleholder with seven lamps sprouting from the mouth of seven rolled-up snakes. Above the main altar, inserting into the ceiling, is a gigantic jasper crucifix of 4.2 m, flanked by two kneeling angels, made by the School of Mafra. The cupola over the crossing was also inspired by the cupola of Sant’Agnese in Agone (by the Roman Baroque architect Francesco Borromini). This 70 m-high cupola with a small lantern atop, is carried by four finely sculpted arcs in rose and white marble.

There are six organs, four of which are located in the transept, constituting a rather uncommon ensemble. There were built by Joaquim Peres Fontanes and António Xavier Machado Cerveira between 1792 and 1807 (when the French troops occupied Mafra). They were made out of partially gilded Brazilian wood. The largest pipe is 6 m high and has a diameter of 0.28 m. King John V had commissioned liturgical vestments from master embroiderers from Genoa and Milan, such as Giuliano Saturni and Benedetto Salandri, and from France. They attest of superb quality and workmanship by their embroidering in gold technique and the use of silk thread in the same colour.

The religious paintings in the basilica and the convent constitute one of the most significant 18th century collections in Portugal. They include works by the Italians Agostino Masucci, Corrado Giaquinto, Francesco Trevisani, Pompeo Batoni and some Portuguese students in Rome such as Vieira Lusitano and Inácio de Oliveira Bernardes. The sculpture collection contains works by almost every major Roman sculptor from the first half of the 18th century. At that time, it represented the biggest single order done by a foreign power in Rome and still is amongst one of the biggest collections in existence.

The parish of Mafra and the Royal and Venerable Confraternity of the Most Blessed Sacrament of Mafra have their headquarters in the Basilica.

The basilica

The Basilica occupies the central part of the building, flanked by the bell towers. It was made according to the design of the architect of German origin Frederico Ludovici, who after his long stay in Italy, conceived it in the Italian Baroque style. It has the shape of a Latin cross with a total length of 58.5 m and a maximum width of 43 m on the cruise, under which the 65 m high and 13 m diameter junction rises. The juniper took two years to build and was finished after being replaced. Forty-one men worked there at the same time, not bothering each other. Eighty-six oxen joints were required for his transportation, accompanied by 612 men who supported him with ropes. This was the first Roman dome built in Portugal.

In addition to the chancel, this church has two chapels on the cruise, Sagrada Familia (south side) and Blessed Sacrament (north side), two side chapels, Our Lady of the Conception, on the side of the Epistle, and St. Peter of Alcantara, on the Gospel side, six side chapels and two halls, plus 45 tribunes.

The railings of the two main chapels were designed by the Slotdz brothers – Sébastien Antoine (1695-1754) and René Michel, said Miguel-Angelo (1705-1764) – and by Sautray. This designed the grid for the High Altar (replaced by a stone balustrade in the time of D. João VI’s regency), executed by the locksmith G. Garnier, installed in the Tuilleries, while the grid of the Chapel of the Blessed Sacrament is by the Slotdz brothers, executed by master-locksmith Destriches of the Arsenal de Paris.

These cancellations were inspected by goldsmith Germain, among others, and were exhibited in Paris in 1730, before being sent to Portugal.

On these railings were placed eight torches that lit up on solemn occasions.

Above the high altar is a sculptural ensemble by Genoese Francesco Maria Schiaffino, representing Christ Crucified, Glory and two angels in worship. The altarpiece of this altar is by Francesco Trevisani and represents The Virgin, Child and St. Anthony, to whom the Basilica is dedicated.

For the Royal Basilica also commissioned the king, to the most prestigious Italian and Portuguese painters of the time, the paintings and telescopes of all the chapels. These paintings were replaced, in the reign of D. José, by marble altarpieces and telescopes executed at the Mafra School of Sculpture, founded here under the direction of the Italian master Alessandro Giusti.

Also noteworthy is the important statuary of the façade, Galilee and interior, by Italian masters, which is the most significant collection of Italian Baroque sculpture outside Italy. There are 58 statues of sculptors such as Carlo Monaldi, Giovanni Battista Miani, Fillipo della Valle or Pietro Bracci, representing the main saints of the Church, the Apostles, the Founders of the most important religious orders, among others.

Organs

The organically designed Basilica of Mafra, conceived from the ground up, is truly groundbreaking in considering an integrated set of six organs rather than two large instruments and three sections, usually linked to the high church choir, as was then usual.

From the outset the architectural project of the basilica includes the placement of six organs in the area of the high altar and the cruise, however we know that in the solemn consecration of the basilica, and not being completed, six porting organs were also used.

The current six instruments were commissioned during the reign of King John VI to replace the degraded primitives. They were built by the two most important Portuguese archers of the time – António Xavier Machado and Cerveira and Joaquim António Peres Fontanes – and were completed between 1806 and 1807.

The 6 instruments are made of holy wood, with brass hardware applications performed in the Lisbon Arsenal representing flowers, garlands, columns and capitals as well as various musical instruments such as horns and violins, writing pens, ink cartridges and music staves. The sculptor Carlo Amattuci was responsible for the medallion with the effigy of D. João VI, in the organ of the Epistle.

Lord Byron, in his letters, referring to this set of organs, writes: “… the most beautiful I have ever seen in terms of decoration.”

In the Library there is an important nucleus of scores of important Portuguese musicians such as João de Souza Carvalho, Marcos Portugal or João José Baldi, which can only be played here.

Chimes

The Royal Convent of Mafra has a set of two chimes that is a series of musically tuned bells. In the case of Mafra there are ninety-eight bells, which makes them one of the largest historical chimes in the world.

According to tradition, at the behest of the King the Marquis of Abrantes sought to find out the price of a carillon and was given the value of 400,000 $ 00 reis, which was considered too high for such a small country. To which D. Joao V, offended – was the richest monarch of his time – replied: “ I did not suppose it was so cheap; I want two! Thus it was executed in Liege, in the workshops of Nicholas Levache, the north tower chime, and in Antwerp, in the foundry of Willem Witlockx, that of the south tower.

Each bell tower had fifty-eight bells, belonging to each forty-nine chime. The first bells each weigh 625 arrobas [1 arroba = 14,688 kg] or over 9,180 kg. Those of second magnitude each weigh 291 arrobas ie 4,270 kg each, those of third 231 arrobos corresponding to 3,392 kg each, those of fourth 99 arrobas weigh 1,454 kg each. each and thus decreasing to 1 bells at the smallest, with about 15 kg each. Finally the chime wheels and mills weigh 1,420 quintals [1 quintal = 58,752 kg] or 83,427.84 kg.

Both chimes are simultaneously composed of two systems:

– The mechanical system functions as a Barbieri organ, with two huge brass cylinders where pegs representing musical notes are placed. When driven by the clock mechanism, the movement of the cylinders causes the dowels to strike metal keys or parrots , moving the bell hammers according to the programmed melody. The mechanical carillon played every room, half an hour, right from sunrise to sunset.

– The manual system is driven by a ranger, playing with his hands and feet on a keyboard that makes the bell clang.

Other bells punctuated the life of the convent, such as the Bell of the Classes, which marked the beginning of these, the Bell of the Ward or the Agony, so called because it was rung when a friar was near death, the refectory bell that rang to signal Finally, Meal bell, also called the cod bell , because it rang only on fast days, on the morning, on the eve of Mass, as Father João de Santa Ana tells us.

Sacristy

The Sacristy is connected to the church by a corridor where men’s confessionals were placed.

At the back of the room is a chapel dedicated to St. Francis, which has, on the altar, a painting by the painter Inácio de Oliveira Bernardes, fellow of D. João V in Rome, representing The Chagas of St. Francis.

On either side of the door are wooden cabinets from Brazil designed to hold the jug of mass wine, the host boxes and “ other similar things ” needed for worship, in addition to the reliquaries that were placed on the altars on solemn holidays.

On the walls on either side are the carved holywood arches with golden bronze handles and locks and the key ring. They are by Félix Vicente de Almeida, Master Carver of the Royal House. In these arches were the priests’ vestments.

The installation of the sacristy was preceded by several detailed requests for information from the monarch, who wanted to know what “ the most modern and best-suited sacristies were … not only for what they belonged to keep… but also for their use. priests… ” , where the confessionals were placed, the place for the storage of the different religious implements in the cupboards and other related information, always with the concern of following the uses of the Papal Chapel.

Lavatory Room

The Lavatory Room served as support to the Sacristy and the Basilica. Here were stored in two cabinets built into the wall, the missal pads and missals and in drawers labeled with the name of each brother, the starch and shoes that each wore in the Altar Ministry.

The bottom of these cabinets was intended for dirty laundry.

On the walls, four large sinks made of stone “ very dreadfully ” with plant motifs and shells, intended for hand washing. Each sink has a large shell-shaped basin and three bronze faucets. The 4 sinks are powered by water tanks embedded in the door and window openings.

On either side of the sinks, two large holywood towel rails for the hand towels. In the center there is another stone cupboard, where were placed the chalices, the pyramids, the cruets and the bells for the Eucharistic celebration.

At the back of this room, a door gives access to the stairs to the Farm Houses, where still today are stored in wooden cabinets from Brazil, the vestments from France and Italy.

Italian sculpture

For the Royal Basilica of Mafra D. João V will order what will be the most significant collection of Baroque sculpture in Italy outside of a total of 58 Carrara marble statues.

This order means by King Magnânimo not only a desire for magnificence and a prestigious effect at the international level, but also an attempt to renew an art form that was not a great tradition in Portugal and which will later serve of model for the formation of national artists.

Thus, the lack of great national sculptors at the time, compels the King to resort to his order in Italy, the great School of Arts of the time. For Mafra work, for example, Carlo Monaldi, Pietro Bracci or Giuseppe Lironi.

The collection includes the terracotta models of the statues sent from Rome for royal approval before their final execution.

Silk

The Joanina Ordering Regiments for the Royal Mafra Convent The gold transformed into silk

The Royal Work of Mafra was born from the will of King D. João V, who brought here the main riches of the Kingdom, namely the important influx of gold from Brazil. King-Maecenas, sought to create in Portugal a true “school of arts” while at the same time elevating his “Royal City” to the splendor of the great European courts, such as the Papal Court or Louis XIV.

To this end, he commissioned an important collection of Italian sculpture and painting in the major artistic centers of the time, sending young artists to study in Rome at his own expense.

To “dress” the Royal Basilica of Mafra, D. João V will also resort to “foreign commission”.

The first references to this collection of “ornaments” of the Basilica appear in the document Relation of the Magnificent Work of Mafra, probably from 1733/35. This is just a list, where the pieces are only listed, without great descriptions. More detailed are the Relation of the Convent of Sancto Antonio de Mafra its officinas and Pallacios that will be founded mystical (?) To the said Convent work without date, but probably written between 1733 and 1744 and in the Sacred Monument of Frei João de São José do Prado, which details the ceremonies of the consecration, of which the author was Master of Ceremonies.

In these are listed the vestments, their color, the classification on more and less solemn days, the typology of the pieces and their provenance, namely from Italy (Genoa and Milan) and France. Some of these ensembles were solemnly blessed on the eve of the first day of the Basilica’s Feast celebrations, but these orders continue until at least 1734.

In Italy, it will be José Correia de Abreu, Customs Major Guard, who, at the behest of D. João V, directs Fr José Maria da Fonseca Évora to the orders for Mafra. Fonseca Évora, a Franciscan friar who will become Bishop of Porto, was Portugal’s ambassador to the Vatican and himself a collector and expert.

From this correspondence we know that the garments should be of “… silk, not damask or plowed, but strong, and very hard… embroidered with gold-colored silk as much as it can be with the same gold. Be the tasteful embroidery design, and work it perfectly. ”

Let us remember that the yellow silk thread (and the yellow color in general) was considered in the Parliamentary as the “gold of the poor”. That is, it was common for a parish that could not buy gold brocade vestments to use the yellow color as a background or, if it could not afford the embroidery in gold thread, to order it in yellow silk thread.

However, this requirement of the vestments for Mafra is not related to financial difficulties – D. João V was the richest monarch in Europe at the time – but to the fact that they were destined for a Franciscan convent bound by a vow of poverty..

Mafra was then commissioned in five liturgical colors, namely white, crimson, green, purple and black.

Roman use since the 19th century. XVI, prescribes the exclusive use of these five colors, which cannot be replaced by others, and the entire fabric must obey the dominant color. However, all shades within the color are allowed.

The color canon covers the chasuble, dalmatics, asperges or raincoat, tunic, stole, handle, gloves, socks and shoes.

According to the said canon, the white vestment was used in the feasts of Our Lord, except those related to the Passion, in all the feasts of Our Lady, the Angels, the Confessors, the Virgins, the Holy Women, the consecration of the churches, the All Saints Day, Holy Spirit feasts and wedding ceremonies

Crimson served at Pentecost, in the feasts of the Precious Blood and Instruments of the Passion, the Apostles and the Martyrs.

The green ornament was used for the Sunday and ferial office of ordinary time, namely after Epiphany and Pentecost.

The purple for Advent, Lent, fasting vigils, the feast of the Innocent Saints, and votive masses of penance or begging.

And finally the black vestment served on Good Friday and at the masses of the dead. Respecting these five liturgical colors, there are embroidered ornaments every day of the year:

All-embroidered white grosgrain ornament for Confessions, All-embroidered white grosgrain ornament for the most solemn days, White embroidered sebastian ornament, made in Genova for the less solemn days, All-embroidered crimson september ornament, made in Genova for the solemn days, crimson grosgrain ornament meyo loose flower embroidery, made in France for the less solemn days, crimson grosgrain ornament with embroidered gallons, and sebastos, made in France for the solemn days masses, green ornament setim meyo embroidery made in Milan, purple setim meyo embroidery ornament made in Milan, setim black meyo embroidery ornament for the solemn Masses of the dead, Ornament for singing the Passion, and purple meyo embroidered ornament for singing the Passion for and others in plain damask, with only gold-colored gallons.

As for France, it will be Francisco Mendes de Gois, Portugal’s agent in Paris, who will handle this order by order of the Cardinal of Mota, to whom his correspondence is addressed.

The “ornaments” came by sea, packed in “polished coffins, with their separations… able to serve the same coffins to keep them…”. These “coffins” are still used today for your accommodation at the Farm House.

The inventory of the time, the material – satin for the Italians, silk grosgrain for the French – the very different decorative grammar of each ensemble allows us to distinguish those who came from France or Italy and, within the Italians, those who come from Genoa or Milan

However, apart from the mentioned correspondence of Fonseca Évora and Francisco Mendes Góis, no other documentation about these pieces is known so far, such as purchase orders or payments, so it is difficult to assign the pieces to specific embroiderers.

The importance of this collection also relates to the high number of pieces that compose it. By way of example, the all-embroidered grosgrain ornament serving as the Confess (or Body of God) has twenty-five chasubles, eight dalmatics, twelve embroidered capes, seventy rainfall, while the crimson grosgrain ornament with embroidered gallons for prayed Masses. on solemn days it has ten chasubles, ten sticks, ten chalice veils and ten body bags

Let us remember that the liturgical vestments of a vestment are usually for one, sometimes two or three celebrants, and not so often. In addition to the celebrations’ vestments, many ensembles also have a missal cover, bookshelf cloth, faldistory cover, pulpit cloth, tabernacle pavilion, altar front, and so on.

All the draperies that served to “dress” the Basilica were commissioned. From France arrived three large crimson canopies embroidered to the three main chapels of the Basilica – Altar-Major, Blessed Sacrament and Holy Family – with their respective pelmet and backrest and six identical gates to the same chapels, eight equal but smaller canopies for the remaining chapels, two more in white silk grosgrain, also with their backrests, for the High Altar and for the Chapel of the Blessed Sacrament and “sister” gates. Also of the same white silk embroidered grosgrain there are eleven smaller canopies, with backrests for the other chapels.

Three tabernacles of the tabernacle arrived, one white for the Confession, another white, all embroidered, and one crimson, just like the meyo embroidery of loose flowers for the less solemn days, plus three – white, crimson and purple – also all embroidered for the small tabernacle.

From Italy came large tabernacle pavilions identical to the Genoese green and purple vestments, plus three for the small tabernacle, all embroidered, in the colors red, purple and white.

There are also two umbrellas, one in white grosgrain, all embroidered, and one in smooth apricot with gallons and fringes “gold” and seven processional banners in different liturgical colors.

Regarding the pieces coming from Paris, the document Relation of the Magnificent Work of Mafra, cited above, says that the white canopies and their gates cost “150 thousand and so many crusaders”, while the reds and purples “will bear more than four hundred thousand crusaders”.

As a matter of curiosity, nineteenth-century sources report having D. João V stated that these “ornaments” had cost him as much as the building itself.

Reference is also made to the ordering of all “vestry white” clothing, such as “two-foot-wide and two-foot-wide cambraya lenses”, “thin-lace sleeves,” ratchets, quotas, towels , body, blood, altar cloths, etc.

The sacristy itself has also been the subject of detailed requests for information on how “the most modern and best-suited sacristies… not only for what they belong to keep… but also for the use of priests…” as they are. made and where the confessionals are placed, the place for storing the different religious implements in the cupboards, etc., always with the concern of following the uses of the Papal Chapel.

Most of these pieces are still part of the Mafra National Palace collections today.

There are also in the Palace’s collection some gold embroidered vestments, after D. João V, which served in the oratories of the Palace and in the Royal Chapel installed here by D. João VI, as well as in the various balconies of the Basilica.

They are, however, quite different both in the materials used – here the llama and the gold and silver thread – and in the decorative grammar.

Mafra National Palace

The Mafra National Palace is located in the municipality of Mafra , in the district of Lisbon in Portugal , about 25 kilometers from Lisbon. It is made up of a monumental palace and monastery in baroque joanine style , on the German side. The work of its construction began in 1717 at the initiative of King D. João V , by virtue of a promise he had made in the name of the offspring he would obtain from Queen D. Maria Ana of Austria.

Built in the 18th century by King João V in fulfillment of a vow to obtain succession from his marriage to D. Maria Ana of Austria or the cure of a disease he suffered, the National Palace of Mafra is the most important monument of the baroque in Portugal.

Constructed in lioz stone of the region, the building occupies an area of nearly four hectares (37,790 m2), comprising 1200 divisions, more than 4700 doors and windows, 156 staircases and 29 courtyards and lobbies. Such magnificence was only possible because of the gold of Brazil, which allowed the Monarch to put into practice a policy of patronage and reinforcement of royal authority.

It is classified as a National Monument and declared a 2019 World Heritage Site by UNESCO.