The French literature of 20th century is part of a tumultuous century marked by two World Wars, by the experience of totalitarian fascist and communist and a decolonization difficult. The literature will also see its status evolve under the effect of technological transformations such as the appearance and development of pocket editions or the competition of other leisure activities such as cinema, television or computer practice. At the same time, there will be a gradual dilution of the aesthetic and intellectual currents after the era of surrealism, existentialism and New Roman.

Overview

French literature was profoundly shaped by the historical events of the century and was also shaped by—and a contributor to—the century’s political, philosophical, moral, and artistic crises.

This period spans the last decades of the Third Republic (1871–1940) (including World War I), the period of World War II (the German occupathe Vichy–1944, the provisional French government (1944–1946) the Fourth Republic (1946–1958) and the Fifth Republic (1959-). Important historical events for French literature include: the Dreyfus Affair; French colonialism and imperialism in Africa, the Far East (French Indochina) and the Pacific; the Algerian War of Independence (1954–1962); the important growth of the French Communist Party; the rise of Fascism in Europe; the events of May 1968. For more on French history, see History of France.

Twentieth century French literature did not undergo an isolated development and reveals the influence of writers and genres from around the world, including Walt Whitman, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Franz Kafka, John Dos Passos, Ernest Hemingway, William Faulkner, Luigi Pirandello, the British and American detective novel, James Joyce, Jorge Luis Borges, Bertolt Brecht and many others. In turn, French literature has also had a radical impact on world literature.

Because of the creative spirit of the French literary and artistic movements at the beginning of the century, France gained the reputation as being the necessary destination for writers and artists. Important foreign writers who have lived and worked in France (especially Paris) in the twentieth century include: Oscar Wilde, Gertrude Stein, Ernest Hemingway, William S. Burroughs, Henry Miller, Anaïs Nin, James Joyce, Samuel Beckett, Julio Cortázar, Vladimir Nabokov, Edith Wharton and Eugène Ionesco. Some of the most important works of the century in French were written by foreign authors (Eugène Ionesco, Samuel Beckett).

From 1895 to 1914

The early years of the century (often called the “Belle époque”) saw radical experiments in all genres and Symbolism and Naturalism underwent profound changes.

In the novel, André Gide’s early works, especially L’Immoraliste (1902), pursue the problems of freedom and sensuality that symbolism had posed; Alain-Fournier’s novel Le Grand Meaulnes is a deeply felt portrait of a nostalgic past.

Popular fiction and genre fiction at the start of the 20th century also included detective fiction, like the mysteries of the author and journalist Gaston Leroux who is credited with the first “locked-room puzzle” — The Mystery of the Yellow Room, featuring the amateur detective Joseph Rouletabille (1908) — and the immensely popular The Phantom of the Opera (1910). Maurice Leblanc also rose to prominence with the adventures of gentleman-thief Arsene Lupin, who has gained a popularity akin to Sherlock Holmes in the Anglophone world.

From 1914 to 1945

Dada and Surrealism

The First World War generated even more radical tendencies. The Dada movement—which began in a café in Switzerland in 1916—came to Paris in 1920, but by 1924 the writers around Paul Éluard, André Breton, Louis Aragon and Robert Desnos—heavily influenced by Sigmund Freud’s notion of the unconscious—had modified dada provocation into Surrealism. In writing and in the visual arts, and by using automatic writing, creative games (like the cadavre exquis) and altered states (through alcohol and narcotics), the surrealists tried to reveal the workings of the unconscious mind. The group championed previous writers they saw as radical (Arthur Rimbaud, the Comte de Lautréamont, Baudelaire, Raymond Roussel) and promoted an anti-bourgeois philosophy (particularly with regards to sex and politics) which would later lead most of them to join the communist party. Other writers associated with surrealism include: Jean Cocteau, René Crevel, Jacques Prévert, Jules Supervielle, Benjamin Péret, Philippe Soupault, Pierre Reverdy, Antonin Artaud (who revolutionized theater), Henri Michaux and René Char. The surrealist movement would continue to be a major force in experimental writing and the international art world until the Second World War. The surrealists technique was particularly well suited for poetry and theater, although Breton, Aragon and Cocteau wrote longer prose works as well, such as Breton’s novel ‘’Nadja’’.

Influence and dissidence

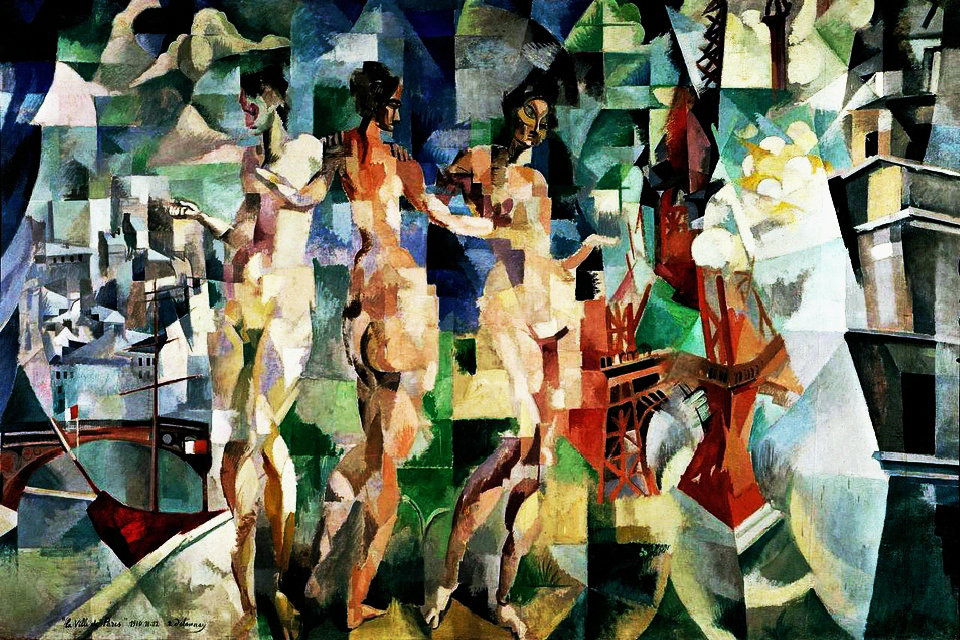

The influence of surrealism will be of great importance on poets like Saint-John Perse or Edmond Jabès, for example. Others, such as Georges Bataille, created their own movement and group in reaction. The Swiss writer Blaise Cendrars was close to Apollinaire, Pierre Reverdy, Max Jacob and the artists Chagall and Léger, and his work has similarities with both surrealism and cubism.

Poetry

French poetry of the 20th century is both heir and innovative in its themes and in its form with a clear preference for free verse, but it seems in decline or at least moved to the more uncertain domain of the song.

The beginnings of the century symbolism, decadence, spiritual poetry

Emile Verhaeren

The beginnings of the century show a great diversity with the legacies of the previous century, whether it is the continuity of the symbolist and decadentist movement with Sully Prudhomme, Saint-Pol-Roux, Anna de Noailles and certain aspects of Apollinaire, the lineage of brain and Mallarmean formal work with Paul Valéry (Charmes, 1922), or the liberation of new themes such as the humility of everyday life with Francis Jammes (The Christian Georgics, 1912) or Paul Fort (French Ballades, 1922-1951) and the opening to the modern world with Émile Verhaeren (Sprawling cities, 1895 – All Flanders, 1904-1911).

In the same years, singular voices are heard with those called “Poets of God” as Charles Peguy with his patriotic and religious inspiration and the strength of a simple poetry (Joan of Arc, 1897 – Tapestry of Eve, 1913), or Paul Claudel with his spiritual quest expressed through the magnitude of the verse (Five Great Odes, 1904 – 1908 – 1910).

The “new spirit” the surrealist revolution

It is also the time of the “discoverers ” as Blaise Cendrars (The Easter in New York, 1912 – The Prose of Transsiberian, 1913), Guillaume Apollinaire (Alcohols, 1913 – Calligrammes, 1918), Victor Segalen (Steles, 1912), Max Jacob (The Dice Cornet, 1917), St. John Perse (Praise, 1911 – Anabasis, 1924, with a prolonged piece of work eg Bitter in 1957) or Pierre Reverdy (Most of the time, 1945, grouping of poems from 1915-1922) that explore the “new spirit” by seeking the presence of modernity and everyday life (the street, the journey, the technique) and the bursting of the form (disappearance of the rhyme, punctuation, metrical verse and stylistic audacities exploiting the expressiveness of images, the resources of rhythm and sounds…). They foreshadow more systematic research like that of Tristan Tzara ‘s dadaism and, after him, surrealism, which gives poetry the exploration of the unconscious by using Rimbaldian disturbances and jostling the “seated”. The automatic writingalso appears in the same goal. The major poets of this surrealist movement are André Breton, the theoretician of the movement with the Manifesto of Surrealism in 1924, Paul Éluard (Capital of Pain, 1926), Louis Aragon (Perpetual Movement, 1926), Robert Desnos (Body and Goods, 1930), Philippe Soupault (The Magnetic Fields, 1920, in collaboration with André Breton) or Benjamin Péret (Le grand jeu, 1928), to which we can associate painters such as Dali, Ernst, Magritte or Miro.

Individual appropriations and overtaking surrealism

Dissidences appear fairly quickly in the group especially about the adhesion to communism, and the violence of history as the Occupation of France will lead many poets to renew their inspiration by participating in the Resistance and publish clandestinely committed texts. This is the case of Louis Aragon (The Eyes of Elsa, 1942 – The French Diana, 1944), Paul Eluard (Poetry and Truth, 1942 – The German rendezvous, 1944), René Char (Feuillets d ‘ Hypnos, 1946) or René-Guy Cadou (Full Chest, 1946). The poets will not be spared by the Nazi extermination: Robert Desnos will die in a German camp and Max Jacob in the Drancy camp.

However, individualities will produce works that will reveal different approaches with Jean Cocteau’s dream-like approach to everything (Plain-Chant, 1923), Henri Michaux’s expressive research (Elsewhere, 1948), the verbal game resumed by Jacques Prévert, poet of the everyday and the oppressed (Paroles, 1946-1949) or Francis Ponge (The bias of things, 1942) in search of a poetry in descriptive prose. All translate emotions and sensations in the celebration of the world with Jules Supervielle (Forgetful memory, 1948) or Yves Bonnefoy(Pierre written, 1965), celebration renewed by voices from elsewhere like that of Aimé Césaire, the Antillean (Cahier of a return to the native country, 1939 – 1960), Léopold Sédar Senghor (Shades of shadow, 1945) or Birago Diop (Lures and Lights, 1960) singing Africa.

Poetry and song

The spread of more and more massive records will strongly participate in a new genre, the sung poetry that illustrated in the years 1950-1970 Boris Vian, Leo Ferré, Georges Brassens, Jacques Brel and Jean Ferrat. The importance of their successors is very delicate to establish, with very variable audiences and effects of fashions like folk song, rap or slam…

Contemporary Poetry

After the war, surrealism lost momentum as a movement, although it strongly influenced the poetic production of the second half of the century. The poets who appear on the poetic scene, such as Yves Bonnefoy, Jacques Dupin, Philippe Jaccottet, or André du Bouchet, deviate from the surrealist paths to favor a poetry in search of authenticity, more suspicious of artifices language and in particular metaphor.

The 1950s saw, in the tradition of Isidore Isou’s Lettrist Movement, sound poetry (Henri Duchamp and the OU magazine) and poetry-action (Bernard Heidsieck). These poets use the tape recorder and the support of the vinyl record to publish a poetry based on the orality even on the sounds.

The 1960s and 1970s also saw a more experimental poetry. This is how the OuLiPo (with Raymond Queneau in particular) proposes to write by imposing formal constraints to stimulate poetic production. It is also the period when literalism develops, practiced notably by Emmanuel Hocquart or Anne-Marie Albiach and theorized by Jean-Marie Gleize.

Following the American “beat” poets and writers, in the late 1960s there appeared a current called “new poetic realism” (Jacques Donguy, 1975 issue of Poetry). This current is represented by authors like Claude Pélieu, Daniel Biga or Alain Jégou.

At the same time, the 1970s saw the emergence of “electric poets”, with Michel Bulteau, Jacques Ferry and Mathieu Messagier. The “electric manifest with eyelids skirts” is published by the publisher of the Black Sun in 1971.

The 1980s are marked by a new lyricism, practiced by poets such as Guy Goffette, Marie-Claire Bancquart, James Sacred or Jean-Michel Maulpoix.

Novel

In the first half of the century the genre of the novel also went through further changes. Louis-Ferdinand Céline’s novels — such as Voyage au bout de la nuit (Journey to the End of Night) — used an elliptical, oral, and slang-derived style to rail against the hypocrisies and moral lapses of his generation (his anti-semitic tracts in the 1940s, however, led to his condemnation for collaboration). Georges Bernanos’s novels used other formal techniques (like the “journal form”) to further psychological exploration. Psychological analysis was also central to François Mauriac’s novels, although he would come to be seen by Sartre as representative of an outdated fatalism. Jules Romains’s 27-volume novel Les Hommes de bonne volonté (1932–1946), Roger Martin du Gard’s eight-part novel cycle The Thibaults (1922–1940), and Marcel Proust’s seven-part masterpiece À la recherche du temps perdu (In Search of Lost Time, 1913–1927) expanded on the roman-fleuve model. André Gide continued to experiment with the novel, and his most sophisticated exploration of the limits of the traditional novel is found in The Counterfeiters, a novel ostensibly about a writer trying to write a novel.

Evolution of the literary novel

This very broad genre sees the continuation of the traditional novel but also innovations and challenges such as those of the status of the narrator, the notion of character or plot, often exploded and sometimes rejected. The presentation outlines the novel of the 20th century (it should perhaps be called “narrative”) is obviously a challenge but we can define some lines of force following the progress of the century.

Accompanying the classical form and the progressive ideas of Anatole France (The Island of the Penguins, 1908), novelists write great romantic cycles constituting social and historical frescoes mark the time, whether Les Thibault (1922-1929) of Roger Martin du Gard, Men of Good Will (1932-1946) of Jules Romains, the Chronicle Pasquier (1933-1945) to Georges Duhamel or more complex works such as the Way Back to Jean-Paul Sartre (1945) and / or The Communists (1949-1951) ofLouis Aragon.

At the same time, the novel will feed on the different experiences of each person’s life by revealing unique itineraries, whether through the war with Henri Barbusse (The Fire, 1916) or Roland Dorgelès (The Wooden Crosses, 1919). adolescence with Alain-Fournier (The Great Meaulnes, 1913), Romain Rolland (Jean-Christophe, 1903-1912) or Raymond Radiguet (The devil in the body, 1923), the feminine condition with Colette and the series of Claudine or La Pussy(1933), nature and regionalism with Louis Pergaud (The war of pimples, 1912), Charles-Ferdinand Ramuz (The great fear in the mountains, 1926), Jean Giono (Hill, 1928 – Regain, 1930), Henri Bosco (The Ass Culotte, 1937) or the moral and metaphysical questioning with Georges Bernanos (Under the sun of Satan, 1926), François Mauriac (Thérèse Desqueyroux, (1927), Charles Plisnier or Joseph Malègue (Augustin or the Master is there).

The psychological deepening novel initiated by Maurice Barrès or Paul Bourget, will find two masters with Marcel Proust and his founding work on the function of the novel and the game of memory (In Search of Lost Time, 1913-1927), and André Gide, also a poet (Les Nourritures Terrestris, 1895) and autobiographer (If the grain does not die, 1920-1924), which stages the free act (Les Caves du Vatican, 1914). This psychological questioning will lead to the next generation on the feeling of the absurd with the character of Meursault in L’Etranger (1942) ofAlbert Camus or Roquentin de La Nausée (1938) existentialist Jean-Paul Sartre. Less prestigious authors can be associated with them like Valery Larbaud (Fermina Márquez, 1911) or Paul Morand (L’Homme in a hurry, 1940).

The weight of historical events will also guide some novelists towards engagement by exalting political and warlike heroes like André Malraux in The Human Condition (1933) or L’Espoir (1937), Antoine de Saint-Exupéry (author of the world famous tale The Little Prince, published in 1943) in Night Flight (1931) or Terre des hommes (1939) or Albert Camus in La Peste (1947). In contrast, the type of anti-hero in the style of Louis-Ferdinand Céline’s Bardamushook by the events and confronted with the nonsense of the oppressor world of the weak on all the continents in Voyage at the end of the night (1932).

These particular thematic orientations are accompanied by a certain formal renewal: Marcel Proust renews the novelistic prose with his sentence-rosace and cultivates the ambiguity as for the author / narrator 16, Louis-Ferdinand Céline invents an oralisante language and André Malraux applies cinematic cutting. With other perspectives, André Breton (Nadja, 1928 and L’Amour fou, 1937) and after him Raymond Queneau (Pierrot my friend, 1942 – Zazie in the subway, 1959), Boris Vian (Foam days, 1947 -The Red Grass, 1950) and Julien Gracq (The Shore of the Syrtes, 1951) introduce a surrealist poeticization. For his part André Gide meticulously organized a complex narrative by multiplying the points of view in The Counterfeiters in 1925, while later Albert Camus played, under the influence of the American novel, with the internal monologue and the rejection of the omniscient focus in The Stranger (1942). In the 1930s Jean Giono relies on the strength of creative metaphors in Regain (1930) or in Le Chant du monde (1934) while Francis Carco (The hunted man, 1922) and Marcel Aymé (The green mare, 1933) or later Albert Simonin (Touch not to grisbi! 1953) exploit the greenness of popular speeches. Many other authors, more unknown, participate in this renewal as René Daumal and his pataphysical approaches, Luc Dietrich with the novel quest for self close to autobiography (The Learning of the City, 1942) or Vladimir Pozner who makes explode narrative and fiction (The Bit Tooth, 1937).

Formal research becomes systematic with the current known as “the new novel” of the fifties at Éditions de Minuit: these “novelists laboratory” work to the disappearance of the narrator, the character, the plot, the chronology for the benefit of the subjectivity and disorder of life, the gross presence of things with especially Alain Robbe-Grillet (Les Gommes, 1953), Michel Butor (The modification, 1957), Claude Simon (The road of Flanders, 1960) and Nathalie Sarraute (The Planetarium, 1959), which stand out then clearly traditional novelists like Françoise Sagan (Hello sadness, 1954), Hervé Bazin (Viper in hand, 1948), Henri Troyat (The light of the righteous, 1959/1963) or Robert Sabatier (Swedish Allumettes, 1969) or François Nourissier (German, 1973).

In addition to these “experimental” novels or these rather insignificant works, the years 1960-80 offer authors of great reputation with strong literary personalities and original and strong works. For example Marguerite Yourcenar (Memoirs of Hadrian, 1951 – The Work to Black, 1968), Marguerite Duras, sometimes related to the movement of the new novel, (Moderato cantabile, 1958 – The lover, 1984), Albert Cohen (Beautiful of the Lord, 1968), Michel Tournier (Friday or the Limbo of the Pacific, 1967 – The King of the Alders, 1970) or JMG Le Clézio (The Minutes, 1963 – Desert, 1980).

The popular novel (detective, historical, science fiction, fantasy…)

The century is also rich profusion of popular forms from the 19th century as the detective story gradually influenced by the thriller American with Georges Simenon (Yellow Dog, 1932) boileau-narcejac (one that was plus, 1952), Léo Malet (Nestor Burma and the Monster, 1946), Jean Vautrin (Canicule, 1982), Jean-Patrick Manchette (“The Little Blue of the West Coast” 1976), Didier Daeninckx (Death forgets person, 1989),Philippe Djian (Blue like hell, 1983), Jean-Christophe Grangé (The purple rivers, 1998)… The historical novel is multiplied with Maurice Druon (The cursed Kings, 1955-1977), Gilles Lapouge (The battle of Wagram, 1987), Robert Merle (Fortune of France, 1977) or Françoise Chandernagor (La Chambre, 2002). Abundant stories of travel and adventure (Henry de Monfreid – The Secrets of the Red Sea, 1932) and novels of action and exoticism withJean Lartéguy (The Centurions, 1963), Jean Hougron (The Indochinese Night, 1950/1958) or Louis Gardel (Fort-Saganne, 1980). The science fiction and fantasy also produce a large number of works with René Barjavel (Night Time, 1968), Michel Jeury (Uncertain Time, 1973), Bernard Werber (Ants, 1991) that… have some difficulty in competing with translated works.

Self-writing

The vein is egocentric, too, very productive with forms more or less innovative of autobiography with Marcel Pagnol (The Glory of my father, 1957), Simone de Beauvoir (Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter, 1958), Jean- Paul Sartre (Words, 1964), Julien Green (Far-away Land, 1966), Nathalie Sarraute (Childhood, 1983), Georges Perec (W or childhood memory, 1975), Marguerite Yourcenar (North Archives, 1977) orHervé Guibert (To the friend who did not save my life, 1990) and self-writing joins the novel in the rather vague genre of autofiction with Patrick Modiano (Rue des Boutiques obscures, 1978).), Annie Ernaux (The Place, 1983), Jean Rouaud (The Fields of Honor, 1990), Christine Angot (Subject Angot, 1998)…

The hard work of language

Another vein illustrates the end of the 20th century, the hard work of the language. Pierre Michon, Yves Charnet, Jean-Claude Demay and Claude Louis-Combet illustrate this trend where the demand for rich writing and a strong sense dominates.

Some very recent authors

Conclude this overview of French novel of the 20th century noting the emergence of a writer combines subjectivity and sociology of the time, Michel Houellebecq.

Theater

Theater in the 1920s and 1930s went through further changes in a loose association of theaters (called the “Cartel”) around the directors and producers Louis Jouvet, Charles Dullin, Gaston Baty and Ludmila and Georges Pitoëff. They produced works by the French writers Jean Giraudoux, Jules Romains, Jean Anouilh and Jean-Paul Sartre, and also of Greek and Shakespearean theater, and works by Luigi Pirandello, Anton Chekhov and George Bernard Shaw. Antonin Artaud 1896-1948 as a poet and playwright revolutions the concept of language, and changes the history and practice of theater.

Persistence of a popular theater

The persistence of the boulevard theater, popular, amusing and satirical is provided by Jules Romains (Knock, 1928), Marcel Pagnol (Marius, 1929 – Topaz, 1933) and by Sacha Guitry (Désiré, 1927 – Quadrille, 1937), Marcel Achard (Jean de la Lune, 1929) – Potato, 1954), André Roussin (Eggs of the Ostrich, 1948) and others, until Agnès Jaoui / Jean-Pierre Bacri (Kitchen and outbuildings, 1989) orYasmina Reza (Art, 1994) today.

A special mention must be made for Jean Anouilh who deepens in a rich and varied work a “moralist” approach of humanity with smiling and squeaky subjects at the same time (Pink Pieces) as the traveler without luggage (1937), L ‘ Invitation to the castle (1947), Cher Antoine (1969), or historical subjects, serious and tragic, (black plays) like Antigone (1944), L’Alouette (1952) or Becket or the honor of God (1959).

The renewal of the literary theater

The first half of the 20th century was also a time of renewal of the literary drama with the dramaturgical totalizing and teeming compositions of Paul Claudel marked by the Christian faith, lyricism and historical evocation (The Satin Slipper, written in 1929 but built in 1943, lasting five hours). A little later, it is through the resumption of ancient myths that will express the tragedy of man and the story sharply perceived in the rise of the perils of the inter-war period and that illustrate Jean Cocteau (Orphée, 1926 – The Infernal Machine, 1934),Jean Giraudoux (The Trojan War will not take place, 1935 – Electra – 1937), Albert Camus (Caligula, written in 1939 but created in 1945) and Jean-Paul Sartre (Les Mouches, 1943). Some of Henry de Montherlant ‘s pieces, such as The Dead Queen (1942) and The Master of Santiago (1947), are nourished by a meditation on History.

This questioning of the world’s march and the influence of Brecht and Pirandello will lead to pieces more politically engaged and nourished by philosophical reflection on action, revolution and individual or social responsibility. Witness the works of Albert Camus (The Siege State, 1948, The Righteous, 1949), Jean-Paul Sartre (The Dirty Hands, 1948) or Jean Genet (Les Bonnes, 1947). The existentialism of Sartre is also expressed in the theater as with No Exit in 1945.

The “theater of the absurd”

The ebb of communist ideology and the complexity of modernity will find their echo in what has been called the ” Theater of the absurd ” which, in the fifties, reflects the loss of benchmarks and distrust vis-à-vis -vis manipulative language. The playwrights, although different from each other and autonomous, represent the void, the wait and, influenced by Antonin Artaud (The Theater and his double, 1938), the emptiness of language through derisory characters, to existence absurd and empty exchanges. This mixture of tragic metaphysics and humor in the derision and destructuration of language and theatrical form (no scenes, very long acts,(The Bald Singer, 1950 – The Chairs – The Lesson – 1951) and more at Samuel Beckett (Waiting for Godot, 1953 – Endgame, 1957).

The contemporary theater

Let us add some names today that show that the theater text remains alive alongside the dramaturgical experiences of current directors: Jean-Claude Grumberg (L’Atelier – 1979), Bernard-Marie Koltès (Roberto Zucco, 1988) or Jean-Claude Brisville (Le Souper, 1989).

Existentialism

In the late 1930s, the works of Hemingway, Faulkner and Dos Passos came to be translated into French, and their prose style had a profound impact on the work of writers like Jean-Paul Sartre, André Malraux and Albert Camus. Sartre, Camus, Malraux and Simone de Beauvoir (who is also famous as one of the forerunners of Feminist writing) are often called “existentialist writers”, a reference to Sartre’s philosophy of Existentialism (although Camus refused the title “existentialist”). Sartre’s theater, novels and short stories often show individuals forced to confront their freedom or doomed for their refusal to act. Malraux’s novels of Spain and China during the civil wars confront individual action with historical forces. Similar issues appear in the novels of Henri Troyat.

In the French colonies

The 1930s and 1940s saw significant contributions by citizens of French colonies, as Aimé Césaire, along with Léopold Sédar Senghor and Léon Damas created the literary review L’Étudiant Noir, which was a forerunner of the Négritude movement.

Literature after World War II

The 1950s and 1960s were highly turbulent times in France: despite a dynamic economy (“les trente glorieuses” or “30 Glorious Years”), the country was torn by their colonial heritage (Vietnam and Indochina, Algeria), by their collective sense of guilt from the Vichy Regime, by their desire for renewed national prestige (Gaullism), and by conservative social tendencies in education and industry.

Inspired by the theatrical experiments in the early half of the century and by the horrors of the war, the so-called avant-garde Parisian theater, “New Theater” or “Theatre of the Absurd” around the writers Eugène Ionesco, Samuel Beckett, Jean Genet, Arthur Adamov, Fernando Arrabal refused simple explanations and abandoned traditional characters, plots and staging. Other experiments in theatre involved decentralisation, regional theater, “popular theater” (designed to bring working classes to the theater), and theater heavily influenced by Bertolt Brecht (largely unknown in France before 1954), and the productions of Arthur Adamov and Roger Planchon. The Avignon festival was started in 1947 by Jean Vilar who was also important in the creation of the T.N.P. or “Théâtre National Populaire.”

The French novel from the 1950s on went through a similar experimentation in the group of writers published by “Les Éditions de Minuit”, a French publisher; this “Nouveau roman” (“new novel”), associated with Alain Robbe-Grillet, Marguerite Duras, Robert Pinget, Michel Butor, Samuel Beckett, Nathalie Sarraute, Claude Simon, also abandoned traditional plot, voice, characters and psychology. To a certain degree, these developments closely paralleled changes in cinema in the same period (the Nouvelle Vague).

The writers Georges Perec, Raymond Queneau, Jacques Roubaud are associated with the creative movement Oulipo (founded in 1960) which uses elaborate mathematical strategies and constraints (such as lipograms and palindromes) as a means of triggering ideas and inspiration.

Poetry in the post-war period followed a number of interlinked paths, most notably deriving from surrealism (such as with the early work of René Char), or from philosophical and phenomenological concerns stemming from Heidegger, Friedrich Hölderlin, existentialism, the relationship between poetry and the visual arts, and Stéphane Mallarmé’s notions of the limits of language. Another important influence was the German poet Paul Celan. Poets working within these philosophical/language concerns—especially concentrated around the review “L’Ephémère”—include Yves Bonnefoy, André du Bouchet, Jacques Dupin, Claude Esteban, Roger Giroux and Philippe Jaccottet. Many of these ideas were also key to the works of Maurice Blanchot. The unique poetry of Francis Ponge exerted a strong influence on a variety of writers (both phenomenologists and those from the group “Tel Quel”). The later poets Claude Royet-Journoud, Anne-Marie Albiach, Emmanuel Hocquard, and to a degree Jean Daive, describe a shift from Heidegger to Ludwig Wittgenstein and a reevalution of Mallarmé’s notion of fiction and theatricality; these poets were also influenced by certain English-language modern poets (such as Ezra Pound, Louis Zukofsky, William Carlos Williams, and George Oppen) along with certain American postmodern and avant garde poets loosely grouped around the language poetry movement (such as Michael Palmer, Keith Waldrop and Susan Howe; with her husband Keith Waldrop, Rosmarie Waldrop has a profound association with these poets, due in no small measure to her translations of Edmond Jabès and the prose of Paul Celan into English).

The events of May 1968 marked a watershed in the development of a radical ideology of revolutionary change in education, class, family and literature. In theater, the conception of “création collective” developed by Ariane Mnouchkine’s Théâtre du Soleil refused division into writers, actors and producers: the goal was for total collaboration, for multiple points of view, for an elimination of separation between actors and the public, and for the audience to seek out their own truth.

The most important review of the post-1968 period — Tel Quel—is associated with the writers Philippe Sollers, Julia Kristeva, Georges Bataille, the poets Marcelin Pleynet and Denis Roche, the critics Roland Barthes, Gérard Genette and the philosophers Jacques Derrida, Jacques Lacan.

Another post-1968 change was the birth of “Écriture féminine” promoted by the feminist Editions des Femmes, with new women writers as Chantal Chawaf, Hélène Cixous, Luce Irigaray…

From the 1960s on, many of the most daring experiments in French literature have come from writers born in French overseas departments or former colonies. This Francophone literature includes the prize-winning novels of Tahar ben Jelloun (Morocco), Patrick Chamoiseau (Martinique), Amin Maalouf (Lebanon) and Assia Djebar (Algeria).

Source from Wikipedia