Two dates, two numbers: a palindromic pair. Can the art of this period also be read from left to right and right to left? Changing the order of factors would undoubtedly alter the product, even though this exhibition, beyond marking the interval between those two years, aspires to highlight its historical and artistic importance but in varying lights, forward and in reverse.

The year 1957 witnessed the culmination of several relevant events in both politics and art. In the political arena, various circumstances within the dictatorial regime led to the end of autocracy and the beginning of developmentalism. In the art world, the influential collectives Equipo 57 and El Paso were born.

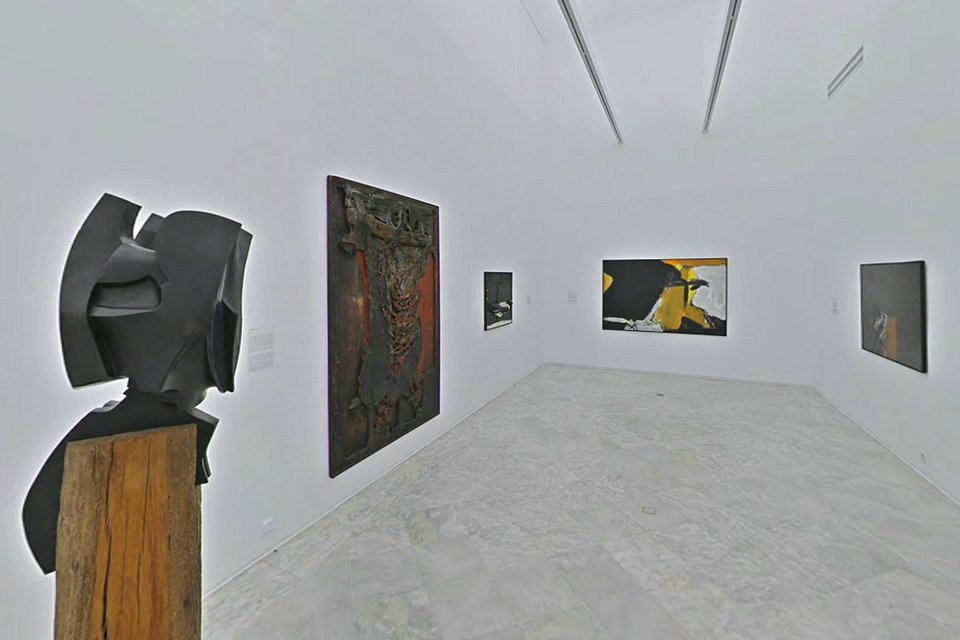

This exhibition, comprising works from the collection of the Centro Andaluz de Arte Contempóraneo, is therefore the beginning of a story divided into chapters or galleries. It is designed to be read initially from the left, starting with the film made in 1957 by Equipo 57, moving on to AFAL (Almería Photographic Association), and later stopping in a large black gallery with pessimistic overtones, expressed through the channels of Art Informel or formal geometric investigations. Expanded, post-pictorial and hard-edge abstraction and models, structures and forms also have their own respective chapters. In contrast, visitors will find important spaces devoted to behavioural art and social corporeal practices, represented by Bruce Nauman, Valie Export, Nacho Criado and Marta Minujín, among others. Finally, the visit ends with a sampling of political Pop Art and early incursions in the New Figuration.

While 1957 was a year of intense artistic developments and hazier political impact, the tables were turned in 1975. In this palindromic interval, it represented a new paragraph in the chapter of Spain’s recent history, marked by a politically significant event —the dictator’s demise— and a new sentence in the paragraph of art, describing the beginning of the end for the abstract and conceptual languages that had shaped and dominated the preceding years, and the rise of figurative trends that would draw attention to several Andalusian artists associated with Madrid’s New Figuration movement. In short, visitors must be prepared to re-read the exhibition narrative in reverse, from right to left, from finish to start, for once they reach the end they will have no choice but to retrace their steps. A truly palindromic experience.

Why the choice of these two dates —57-75—, of this issue capicúa to highlight the temporal scope of the retrospective? Precisely because of its intention: that intrinsic double reading that invites reflection. Could the art produced in this period be read from left to right in the same way as from right to left? In a way, it would not matter to read from beginning to end or vice versa. However, what the sample tries to highlight is the opposite: the order of the factors, in this case, does alter the product. Hence the division into two blocks.

Beginning the narration from the left, at the beginning, we start in 1957, the date in which a series of diffuse political events occur in Spain — the end of autarky, the beginning of a certain development — but very relevant in the field. Artistic: those who open the first chapter of the exhibition with the projection of the film that Team 57 —group of Cordovan artists that was unveiled at the Rond Point café in Paris through the publication of its manifesto by the Interactivity of the plastic space- He made that same year, to end the tour with political pop and the first forays of the New Figuration. All this without forgetting the expanded abstraction, the informalism or the art of behavior and the social practices of the body.

Seen since 75, with the death of Franco as a historical key and turning point towards a radical change, from the artistic point of view there is a certain continuity since that is when the decline of the abstract and conceptual languages that had marked and once this period has been mastered, they give way to figurative trends that are close to reaching their peak. This implies traveling the reverse path, from the end to the beginning; an artistic trip definitely capicúa.

In addition to the two hundred works —among painting, sculpture, video, installation and photography— by abstract and conceptual artists such as Nacho Criado, Marta Minujín, AFAL, Grupo Crónica, Rafael Canogar, Robert Limós, Alfredo Alcaín, Manolo Millares, Antonio Saura, Guillermo Pérez Villalta or Bruce Nauman, the exhibition is completed with an interesting documentation related to the three art galleries that marked a milestone in the introduction of the latest artistic trends in Seville in the 60s and 70s: La Pasarela, Juana de Aizpuru and the M-11 gallery. As well as clandestine publications and posters from the CCOO Historical Archive that contextualize the political and social moment of these two artistic decades.

The year 1957 is considered to be the end of autarky and the beginning of developmentalism, a period in which the so-called Equipo 57 and the group El Paso and other artists who will oscillate “between Marxism, begin their journey” and existentialism. ”

A member of Equipo 57, Juan Cuenca recalled how trying to explain how he and his colleagues understood “plastic space” they had the idea in 1957 to make a cinema movie using the technique of cartoons and based on a collection of abstract gouaches, for which they traveled to Madrid and looked for technicians who could make the film for them.

Among the concerns of these artists in those years, was “promoting art schools and entering the world of graphic design”, although this was done from cities such as Córdoba, as was their case, and without giving up be “very active” against the dictatorship.

José Ramón Sierra has shown one of his works, dated in 1965 and composed with a predominance of black, a color that still dominates today in his creations, and for which he used part of an old threshing he found forgotten in a loft in his house.

The exhibition spans nine CAAC rooms that, according to Álvarez Reyes, “function as independent micro-stories, but with connections to one another”, dedicated to Equipo 57, to the Andalusian association of photographers created in 1956, AFAL, called informalism, art conceptual and, among others, to galleries such as Juana de Aizpuru, M-11 and La Pasarela.

Highlights

EQUIPO 57 (1957 – 1962)

Film Experience nº 1. Theory: Interactivity of the Plastic Space

Interactivity Film I

Consisting largely of artists from Córdoba, Equipo 57 made its debut at an exhibition held at Le Rond Point in Paris in June 1957. At that time, they published a text presenting their programmatic aspirations, which was soon followed by the manifesto Interactivity of the Plastic Space, released for the exhibition at Madrid’s Sala Negra in November of that same year. The formal roots of Equipo 57 can be found in Oteiza’s studies of space and the geometric abstractions of the 1950s, especially the concrete art of Swiss artist Max Bill. However, as an avant-garde group much of their activity focused on social outreach and activism. In the early days they advocated the disappearance of the artist and his subjective vision in favour of the anonymity of collective work. Art had to serve and adapt to the needs of a new society, where man would fight for the common good rather than for his own benefit.

In this social aspect, Equipo 57 was strongly influenced by the Russian avant-garde movements. They also took a stand against the institutionalization of art and the art market, attempting to sell their works at cost.

The group’s early plastic principles—space as a continuous whole where the basic elements of painting (form, line and colour) were integrated and interacted with each other as equals—were reflected in paintings and drawings. In addition, the 24 gouaches displayed in this room were also taken to the filmic experience. Finally, like all utopian dreams, Equipo 57’s lofty ambitions came up against the unyielding wall of reality, creating a sense of frustration that caused some members to drift away. The group found it increasingly difficult to operate and eventually disbanded around 1963, but their ideas remain in the memory of Spanish art as one of the most radical and intense attempts to change the course of history through artistic action.

Almería Photographic Association (Almería, 1956 – 1963)

In the 1950s the AFAL or Almería Photographic Association, which brought together the best Spanish photographers of that generation, set out to renew contemporary photography and defy prevailing academic conventions. Searching for a new sensibility through new aesthetics, its members were united by their involvement with the AFAL journal, first released in 1956. However, the AFAL was not a clearly defined movement but rather a band of individuals interested in very different aspects of photographic creation, from photojournalism and formal investigation to intimist exploration.

Joan Colom (Barcelona, 1921)

Was a member of AFAL and of the collective “El Mussol”, with whom he shared a love of the ordinary and an ethical commitment to freedom of expression that transcended all academicism and political censure. His photographic work adopted the form of thematic series, which allowed him to paint a complete picture of the urban settings he portrayed. Like a notary of reality, in these images Joan Colom certifies the authenticity of everyday life in a Barcelona slum known today as El Raval. For security reasons he took the photos clandestinely, keeping the camera hidden and not looking through the viewer, which allows these pictures to narrate a reality that the eyes of the official city cannot see.

Gabriel Cualladó (Valencia, 1925 – Madrid, 2003)

Cualladó defined himself as a photographe whose likings were inclined to “the essentially humane theme”. His aim was always to highlight “moments of existence” of the human being and to capture precise and unique moments, even though he later showed them blurred. He would also try to capture the atmosphere of the moment in which the photographer “freezes” the scene and would add a poetical perspective to the images, which was in contrast with the hardness of the themes covered.

Paco Gómez (Pamplona, 1918 – Madrid, 1998)

His primary interest look focused on the urban landscape, abandoned buildings in vacant, inhospitable places on the verge of being swallowed up by the sprawling city, where, as the artist himself once, “all is quiet, all is still, […] all is far from the snapshot”, a comment that denotes the kind of premeditated photography that he was doing.

Gonzalo Juanes (Gijón, 1923 – 2014)

Juanes produced black-and-white and colour snapshots using a highly personal, nonacademic technique that resulted in spontaneous works brimming with vitality but which are also contemplative and critical. His photographic praxis focuses essentially on people and urban spaces, creating reportage-style psychological portraits in which anonymous stories that usually had the city as a background.

Ramón Masats (Caldes de Montbui, 1931)

Masats contributed to this renewal of photography by introducing Spain to the language of French documentary photography and applying it in his journalism assignments. Masats´s work on Las Ramblas in Barcelona represented his first attempt at mastering this genre, and his graphic report on Los Sanfermines (the running of the bulls in Pamplona) is a seminal work featuring one the recurring themes of his professional career – Spanish clichés. His photographic style shuns traditional language, defying conventions.

Xavier Miserachs (Barcelona, 1937 – 1998)

He dedicated his life to photography, advertising, reportage, book photography, teaching and even film. He was one of the leading advocates of the renewal of Spanish photography and helped to create a new photographic language. His photography features the city in all its facets, from its architecture and streets to its inhabitants, and few can rival his skill at capturing the urban context in an immediate, spontaneous way. Miserach´s works are a complete documentary of his time.

Francisco Ontañón (Barcelona, 1930 – 2008)

Ontañón began his career in 1959 as a photojournalist for the news agency Europa-Press, a job that allowed him to travel all over the world covering current events. He was sent on assignment to the United States, birthplace of many of the photographers he most admired, as well as different locations throughout Spain. As these photographs clearly show, he preferred fast-paced reporting to carefully arranged studio photography, always striving to capture the event as it occurred, to freeze the moment. He produced a considerable number of works dedicated to Holy Week celebrations in Andalusia. His choice of subject was not accidental, for Holy Week was one of the few subjects fully sanctioned by the political regime in power at the time. In the photographer’s own words, “You couldn’t just photograph whatever you wanted. There was a state censor. The only outlets were the bullfights, flamenco and things like that.” In these works, the spotlight is on the people on the street.

Carlos Pérez Siquier (Almería, 1930)

He was looking to make a testimony of what he saw, taking a respectful approach to the people and situations he captured with his camera. In 1957 he started his work on the slum district of La Chanca, which emerged in Almería in the early 20th century amidst the ruins of an old poor quarter from Moorish times. Rather than highlighting the evident poverty of its inhabitants, Pérez Siquier focused his view on the inner lives and daily routine of his subjects. “I was interested in the people themselves”, says the artist, “their personal dignity in the face of humble circumstances and the difficulties of survival”.

Alberto Schommer (Vitoria, 1928 – San Sebastián, 2015)

Mainly focused his work on themes like still life, studio portraits, the street, landscapes and photographic reports, giving much importance to light and technique. From an aesthetic point of view his photography is closer to the premises of Salon Photography, and although his aim was to show a new way of seeing and feeling photography, he always treated it from a classical perspective. It was in his still lifes and exterior scenes where he used, with more freedom, high and low angles, off-centres and soft focus effects, as well as more arbitrary dispositions and framing.

Ricard Terré (Sant Boi de Llobregat, 1928 – Vigo, 2009)

As Arturo Llopis, one of the group’s critics wrote, Terré “has approached the machine, the shutter release, with very sharp sensitivity and with a previous contact with painting, sculpture and jazz/classical music. In the photographic pieces he presents in black and white, only with his camera, without tricks even in developing, he is harassed by a series of themes (…) A poetical feeling leads the eye of the lens to look for the humane anecdote, accomplished with the lost girl in the middle of the crowd. The object also acquires in Terré an expressive plastic force of enormous quality (…)”

Julio Ubiña (Santander, 1922 – Barcelona, 1988)

Ubiña moved to Paris during the Spanish Civil War, when he was still a teenager. On returning to Spain he settled down in Barcelona, where he set up the first colour photography laboratory. He produced numerous photographic features for prestigious international magazines such as Stern and Paris Match, and although he belonged to the AFAL group he was not an active member. In 1958 Ubiña had participated in the AFAL journal´s monographic issue dedicated to Holy Week. These works are a reflection of the 1950s society, and of some of its most significant components, such as the power of public order, the Civil Guard and the police and the religious figures of the penitents in the processions, understood as popular prints.

Andalusian Contemporary Art Center

The Centro Andaluz de Arte Contemporáneo (CAAC) was created in February 1990 with the aim of giving the local community an institution for the research, conservation and promotion of contemporary art. Later the centre began to acquire the first works in its permanent collection of contemporary art.

In 1997 the Cartuja Monastery became the centre’s headquarters, a move which was to prove decisive in the evolution of the institution. The CAAC, an autonomous organisation dependent on the Andalusian Government (Junta de Andalucía), took over the collections of the former Conjunto Monumental de la Cartuja (Cartuja Monument Centre) and the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Sevilla (Contemporary Art Museum of Seville).

From the outset, one of the main aims of the centre has been to develop a programme of activities attempting to promote the study of contemporary international artistic creation in all its facets. Temporary exhibitions, seminars, workshops, concerts, meetings, recitals, film cycles and lectures have been the communication tools used to fulfil this aim.

The centre’s programme of cultural activities is complemented by a visit to the monastery itself, which houses an important part of our artistic and archaeological heritage, a product of our long history.