Fashion in fourteenth-century Europe was marked by the beginning of a period of experimentation with different forms of clothing. Costume historian James Laver suggests that the mid-14th century marks the emergence of recognizable “fashion” in clothing, in which Fernand Braudel concurs. The draped garments and straight seams of previous centuries were replaced by curved seams and the beginnings of tailoring, which allowed clothing to more closely fit the human form. Also, the use of lacing and buttons allowed a more snug fit to clothing.

General trends

During the course of the century the length of the hem of women’s clothes gradually decreased, and towards the end of the century the tendency for men to renounce the long overcoats, used in previous years, became widespread. On the contrary, the upper part of men’s clothing consisted of garments that fell just below the waist, creating the silhouette that is still part of the male costume today.

From this century on, European fashion changed at a new and unknown pace to other civilizations, both ancient and contemporary. In other cultures, only radical political changes, had produced radical changes in costume and clothing and in fact in Eastern cultures, such as Chinese or Japanese, fashion changed very little in the course of history.

While in the French court, during the reign of Charles VI of France, the taste for luxury was spreading and revolutionary innovations were developing in the field of textile and clothing materials.

Women’s clothing

Underwear

The innermost layer of a woman’s clothing was a linen or woolen chemise or smock, some fitting the figure and some loosely garmented, although there is some mention of a “breast girdle” or “breast band” which may have been the precursor of a modern bra.

Women also wore hose or stockings, although women’s hose generally only reached to the knee.

All classes and both sexes are usually shown sleeping naked—special nightwear only became common in the 16th century—yet some married women wore their chemises to bed as a form of modesty and piety. Many in the lower classes wore their undergarments to bed because of the cold weather at night time and since their beds usually consisted of a straw mattress and a few sheets, the undergarment would act as another layer.

Gowns and outerwear

Over the chemise, women wore a loose or fitted gown called a cotte or kirtle, usually ankle or floor-length, and with trains for formal occasions. Fitted kirtles had full skirts made by adding triangular gores to widen the hem without adding bulk at the waist. Kirtles also had long, fitted sleeves that sometimes reached down to cover the knuckles.

Various sorts of overgowns were worn over the kirtle, and are called by different names by costume historians. When fitted, this garment is often called a cotehardie (although this usage of the word has been heavily criticized) and might have hanging sleeves and sometimes worn with a jeweled or metalworked belt. Over time, the hanging part of the sleeve became longer and narrower until it was the merest streamer, called a tippet, then gaining the floral or leaflike daggings in the end of the century.

Sleeveless overgowns or tabards derive from the cyclas, an unfitted rectangle of cloth with an opening for the head that was worn in the 13th century. By the early 14th century, the sides began to be sewn together, creating a sleeveless overgown or surcoat.

Outdoors, women wore cloaks or mantles, often lined in fur. The houppelande was also adopted by women late in the century. Women invariably wore their houppelandes floor-length, the waistline rising up to right underneath the bust, sleeves very wide and hanging, like angel sleeves.

Headdresses

As one might imagine, a woman’s outfit was not complete without some kind of headwear. As with today, a medieval woman had many options- from straw hats, to hoods to elaborate headpieces. A woman’s activity and occasion would dictate what she wore on her head.

The middle ages, particularly the 14th and 15th centuries, were home to some of the most outstanding and gravity-defying headwear in history.

Before the hennin rocketed skywards, padded rolls and truncated and reticulated headdresses graced the heads of fashionable ladies everywhere in Europe and England. Cauls, the cylindrical cages worn at the side of the head and temples, added to the richness of dress of the fashionable and the well-to-do. Other more simple forms of headdress included the coronet or simple circlet of flowers.

Northern and western Europe

Married women in Northern and Western Europe wore some type of headcovering. The barbet was a band of linen that passed under the chin and was pinned on top of the head; it descended from the earlier wimple (in French, barbe), which was now worn only by older women, widows, and nuns. The barbet was worn with a linen fillet or headband, or with a linen cap called a coif, with or without a couvrechef (kerchief) or veil overall. It passed out of fashion by mid-century. Unmarried girls simply braided the hair to keep the dirt out.

The barbet and fillet or barbet and veil could also be worn over the crespine, a thick hairnet or snood. Over time, the crespine evolved into a mesh of jeweler’s work that confined the hair on the sides of the head, and even later, at the back. This metal crespine was also called a caul, and remained stylish long after the barbet had fallen out of fashion. For example, it was used in Hungary until the beginning of the second half of the 15th century, as it was used by the Hungarian queen consort Barbara of Celje around 1440.

Italy

Uncovered hair was acceptable for women in the Italian states. Many women twisted their long hair with cords or ribbons and wrapped the twists around their heads, often without any cap or veil. Hair was also worn braided. Older women and widows wore a veil and wimple, and a simple knotted kerchief was worn while working. In the image at right, one woman wears a red hood draped over her twisted and bound hair.

Style gallery

1 – Italian gowns |

2 – Barbet and fillet |

3 – Women dining |

4 – In a garden |

5 – Hood |

|---|---|---|---|---|

6 – Italian fashion |

7 – Bride and ladies |

8 – Houppelande |

9 – Hungarian fashion |

10-hawking woman |

11-Women making pasta |

12-Italian women wear hair twisted |

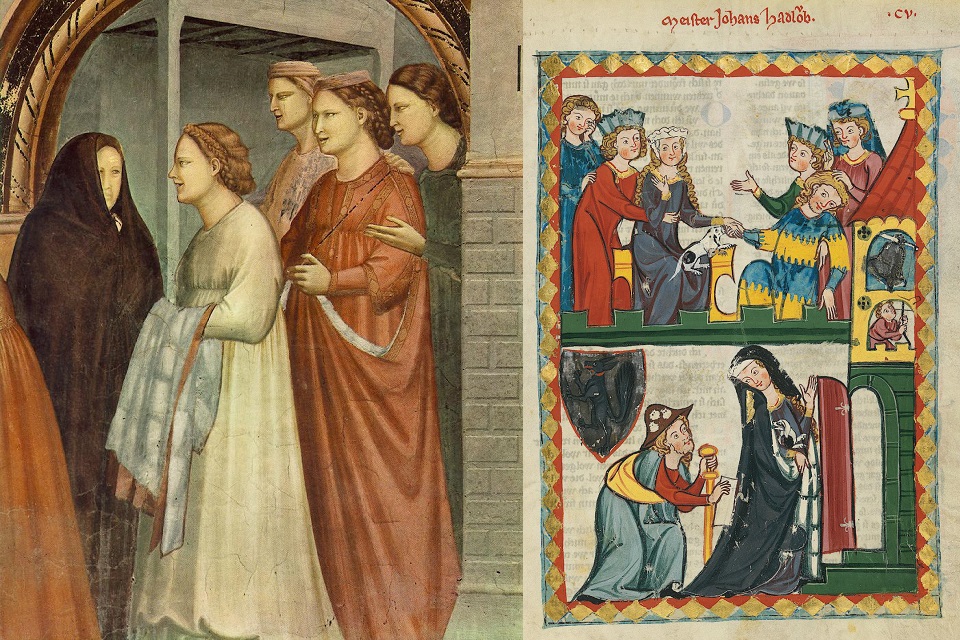

1.Italian gowns are high-waisted. Women’s hair was often worn uncovered or minimally uncovered in Italy. Detail of a fresco by Giotto, 1304–06, Padua.

2.Woman presenting a chaplet wears a linen barbet and fillet headdress. She also wears a fur-lined mantle or cloak, c. 1305–1340.

3.Women at dinner wear their hair confined in braids or cauls over each ear, and wear sheer veils. The woman on the left wears a sideless surcoat over her kirtle, and the woman on the right wears an overgown with fur-lined hanging sleeves or tippets. Luttrell Psalter, England, c. 1325–35.

4.Woman in a garden on a breezy day. Her kirtle sleeves button from the elbow to the wrist, and she wears a sheer veil confined by a fillet or circlet. Her skirt has a long train. Luttrell Psalter, c. 1325–35.

5.Illustration from the French Romance of Alexander, 1338–44, shows a woman wearing a red hood on her head and an overgown with vair-lined hanging sleeves or tippets

6.Italian fashion of this period features broad bands of embroidered or woven trim on the overgown and around the sleeves. Siena, c. 1340

7.A bride wears a long fur-lined gown with hanging sleeves over a tight-sleeved kirtle, with a veil. Her gown is trimmed with embroidery or (more likely) braid. A royal lady wears a blue mantle hanging from her shoulders; her hair is worn in two braids beneath her crown, Italy, 1350s.

8.An indiscreet young woman wears an early houppelande and poulaines, the long pointed shoes that would be worn through most of the next century by the most fashionable. Her hair is wrapped and twisted around her head, late 14th century.

Footwear

9.Hungarian fashion (Elizabeth of Poland, Queen of Hungary and her children. Chronicon Pictum)

10.For hawking, this woman wears a pink sleeveless gown over a green kirtle, with a linen veil and white gloves. Codex Manesse, 1305–40.

11.Women making pasta wear linen aprons over their gowns. Their sleeves are unbuttoned at the wrist and turned up out of the way, late 14th century

12.Many Italian women wear their hair twisted with cord or ribbon and bound around their heads, c. 1380

Footwear during the 14th century generally consisted of the turnshoe, which was made out of leather. It was fashionable for the toe of the shoe to be a long point, which often had to be stuffed with material to keep its shape. A carved wooden-soled sandal-like type of clog or overshoe called a patten would often be worn over the shoe outdoors, as the shoe by itself was generally not waterproof.

Common people

Reflecting the trend, the decollete tends to be wider and the waist becomes narrower.

On the chemise and the shoes, she wore a cot and covered a coarse woolen veil or wimple. There was a thing called a sleeve as a stylish only for Sunday of ordinary women. This was like an arm cover with embroidery etc. It was treated as a detachable sleeve.

Upper class

There is a deformed Mi • Party’s deformed embroidery or applique with embroidery or applique of her father’s emblem on the right side of the lady’s coatardy, on the left side. Cotardi ‘s sleeves had long – sleeved buttons tightly closed with buttons, but most of them had a hanging cloth like Tippet at the cuffs with a quarter – to – quarter sleeve.

The low waist also faded into the decollete which was drawn in the trapezoid, but the extreme high waist which tightens the cloth band which the neck is large in the V letter and the embroidered under the chest is fastened is also prevalent at the same time. The belts fastened to these dresses were embroidered on velvet etc and gold metal fittings were gorgeous. The type with open breasts has fur on the neck, with an inverted triangle covering embroidered on the waist from the chest. I got mantle called Mantel • Danul.

It is fashionable to hairstyled hair which braids three braided hair style on both sides of the head. It covers this with a hair net named Crispin, and furthermore from outdoors etc., it covers Voile Anne Gimp (hooded hood) etc from above.

Hats such as the deformation of Escofion Corno (the high hat suffered by the Governor and the wife of the Governor) were fashionable, and there were various kinds such as two corners and a heart shaped one. It is said that Henin cap which is said to be a variant was brought in from Syria, and it was a high conical type hanging a veil from the tip. A large amount was popularized and hair removal of the bangs and the like was done so that the hair would not protrude from the hat.

Fabrics and furs

Wool was the most important material for clothing, due to its numerous favorable qualities, such as the ability to take dye and its being a good insulator. This century saw the beginnings of the Little Ice Age, and glazing was rare, even for the rich (most houses just had wooden shutters for the winter). Trade in textiles continued to grow throughout the century, and formed an important part of the economy for many areas from England to Italy. Clothes were very expensive, and employees, even high-ranking officials, were usually supplied with, typically, one outfit per year, as part of their remuneration.

Woodblock printing of cloth was known throughout the century, and was probably fairly common by the end; this is hard to assess as artists tended to avoid trying to depict patterned cloth due to the difficulty of doing so. Embroidery in wool, and silk or gold thread for the rich, was used for decoration. Edward III established an embroidery workshop in the Tower of London, which presumably produced the robes he and his Queen wore in 1351 of red velvet “embroidered with clouds of silver and eagles of pearl and gold, under each alternate cloud an eagle of pearl, and under each of the other clouds a golden eagle, every eagle having in its beak a Garter with the motto hony soyt qui mal y pense embroidered thereon.”

Silk was the finest fabric of all. In Northern Europe, silk was an imported and very expensive luxury. The well-off could afford woven brocades from Italy or even further afield. Fashionable Italian silks of this period featured repeating patterns of roundels and animals, deriving from Ottoman silk-weaving centres in Bursa, and ultimately from Yuan Dynasty China via the Silk Road.

A fashion for mi-parti or parti-coloured garments made of two contrasting fabrics, one on each side, arose for men in mid-century, and was especially popular at the English court. Sometimes just the hose would be different colours on each leg.

Checkered and plaid fabrics were occasionally seen; a parti-colored cotehardie depicted on the St. Vincent altarpiece in Catalonia is reddish-brown on one side and plaid on the other, and remains of plaid and checkered wool fabrics dating to the 14th century have also been discovered in London.

Fur was mostly worn as an inner lining for warmth; inventories from Burgundian villages show that even there a fur-lined coat (rabbit, or the more expensive cat) was one of the most common garments. Vair, the fur of the squirrel, white on the belly and grey on the back, was particularly popular through most of the century and can be seen in many illuminated manuscript illustrations, where it is shown as a white and blue-grey softly striped or checkered pattern lining cloaks and other outer garments; the white belly fur with the merest edging of grey was called miniver. A fashion in men’s clothing for the dark furs sable and marten arose around 1380, and squirrel fur was thereafter relegated to formal ceremonial wear. Ermine, with their dense white winter coats, was worn by royalty, with the black tipped tails left on to contrast with the white for decorative effect, as in the Wilton Diptych above.

Source from Wikipedia